Imagine a conversation unfolding not through sound waves or visual cues, but through the delicate dance of vibrations on your fingertips. Picture yourself placing your hand on a speaker’s face and, through the subtle movements of their lips, the hum in their throat, and the puff of air from their mouth, you begin to understand their words. This is not a scene from science fiction; this is the reality for users of the Tadoma method, one of the most remarkable and rare tactile communication systems ever devised.

For those of us who perceive language primarily through hearing, the idea of “feeling” speech is mind-boggling. Yet, Tadoma stands as a profound testament to the adaptability of the human brain and the abstract, multi-modal nature of language itself. It’s a linguistic marvel that pushes the boundaries of what we consider communication.

What Exactly is the Tadoma Method?

At its core, Tadoma is a method of speechreading (or lipreading) by touch. It is primarily used by individuals who are deafblind. The receiver places their hand on the speaker’s face and neck to feel the physical movements associated with speech production. The typical hand placement is highly specific, designed to capture the maximum amount of phonetic information:

- The thumb rests lightly on the speaker’s lips to feel their opening, closing, and rounding.

- The index finger is placed on the side of the nose to detect nasal vibrations.

- The middle finger rests on the jaw or cheekbone to feel jaw movement and muscle tension.

- The ring and pinky fingers are positioned on the throat, near the larynx (voice box), to feel vibrations.

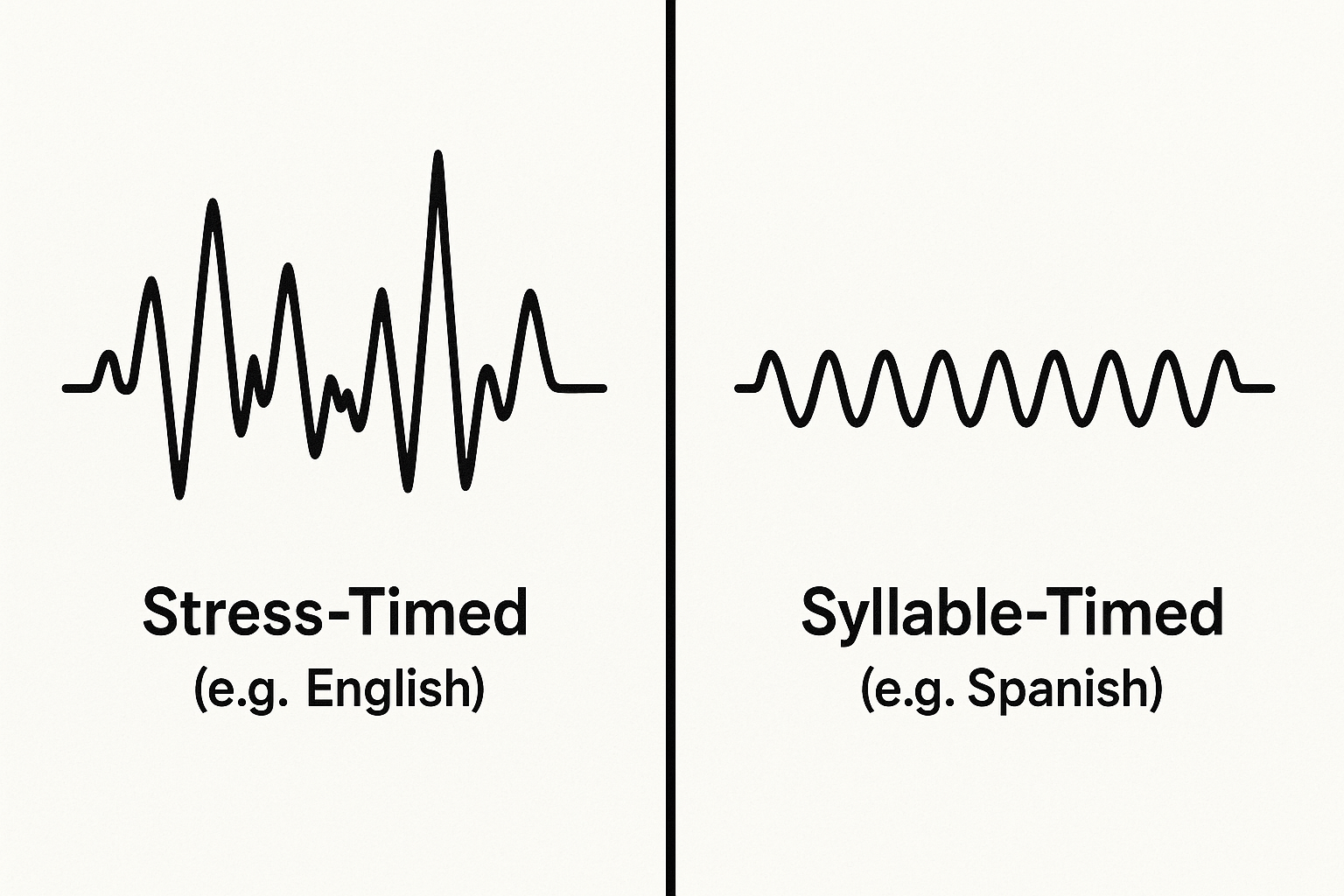

From this single point of contact, a skilled Tadoma user can decipher a rich stream of linguistic data. They feel the sharp pop of a /p/ or /b/ on the lips, the continuous hum of an /m/ or /n/ in the nose, the rise and fall of the jaw for different vowels, and the critical “buzz” in the throat that distinguishes a voiced consonant like /z/ from its unvoiced counterpart, /s/.

The Linguistic Genius of Feeling Phonemes

To understand Tadoma is to appreciate the physical reality of phonetics. Every sound we make has a tangible, physical signature. Tadoma users become masters of interpreting these signatures, essentially becoming tactile phoneticians. Their brain learns to map these complex sensations to the fundamental building blocks of language.

Let’s break down the features they are detecting:

- Voicing: The fingers on the throat are the voicing detectors. They can instantly distinguish between pairs like pat and bat, fan and van, or sip and zip based entirely on the presence or absence of laryngeal vibration.

- Place of Articulation: The thumb is crucial for determining where a sound is made. It feels the lips coming together for bilabial sounds (/p/, /b/, /m/) and the interaction of teeth and lips for labiodental sounds (/f/, /v/). Information from the jaw movement (felt by the middle finger) helps distinguish these from sounds made further back in the mouth, like /t/ or /k/.

- Manner of Articulation: The way air is released is a key piece of the puzzle. A Tadoma user can feel the difference between:

- Plosives (Stops): A sudden puff of air against the hand for sounds like /p/ and /t/.

- Fricatives: A continuous, gentler stream of air for sounds like /f/ and /s/.

- Nasals: A distinct vibration felt by the index finger on the nose for /m/, /n/, and /ng/.

Perhaps the most incredible skill is interpreting coarticulation—the way speech sounds blend together. In natural speech, we don’t produce isolated phonemes. The /a/ in “cat” is different from the /a/ in “cab” because of the sounds that surround it. A Tadoma user must process a continuous, flowing stream of overlapping movements and vibrations, a cognitive feat of immense proportions.

A Brief History and Notable Users

The Tadoma method gets its name from its first two students, Tad Chapman and Oma Simpson, at the Perkins School for the Blind in the early 20th century. While it was taught for several decades, it was never a widely adopted system due to its extreme difficulty.

The most famous individual associated with the technique is Helen Keller. While she is renowned for learning language through Anne Sullivan finger-spelling into her palm, Keller also used Tadoma. She would place her hands on her teacher’s face not just to understand speech, but also to learn how to produce it herself. By feeling the correct formation of sounds, she was able to modulate her own voice and pronunciation, bridging the gap between perception and production.

Why is Tadoma So Rare Today?

Despite its effectiveness for a select few, Tadoma has largely fallen out of use. There are several reasons for its decline:

- Intense Difficulty: Mastering Tadoma requires years of dedicated, one-on-one instruction and incredible sensitivity and concentration. It is not a skill that can be acquired casually.

- Physical Intimacy: The method requires constant physical contact with the speaker’s face, which can be impractical or socially awkward in many situations, especially with strangers.

- Technological Advances: The rise of superior assistive technologies has provided more accessible alternatives. Cochlear implants have restored hearing for many. Powerful digital hearing aids, screen readers, refreshable braille displays, and text-to-speech software have opened up the world of communication in ways that were once unimaginable.

- Tactile Sign Language: For many deafblind individuals today, tactile signing (or “haptic communication”) is a more common method. This involves the receiver placing their hands over the signer’s hands to feel the shape, location, and movement of the signs.

A Window into the Brain and Language

The legacy of Tadoma extends far beyond its practical application. For linguists and neuroscientists, it offers a stunning example of neuroplasticity. The brain of a Tadoma user rewires itself, dedicating parts of the somatosensory cortex (the area that processes touch) to the complex task of decoding language—a job normally handled by the auditory cortex.

Tadoma proves that language is not inherently auditory. It is an abstract system of patterns and structures that can be mapped onto different sensory inputs. Whether perceived as sound waves, written symbols, or facial vibrations, the underlying linguistic system remains. It reminds us that communication is a deeply human drive, and in the absence of one sense, another can be trained to take its place in the most extraordinary ways.

While few people will ever “feel” a conversation, the story of the Tadoma method is a powerful reminder that language is more than just spoken words. It is a current of connection that can flow through touch, a testament to human resilience and the boundless potential of the mind.