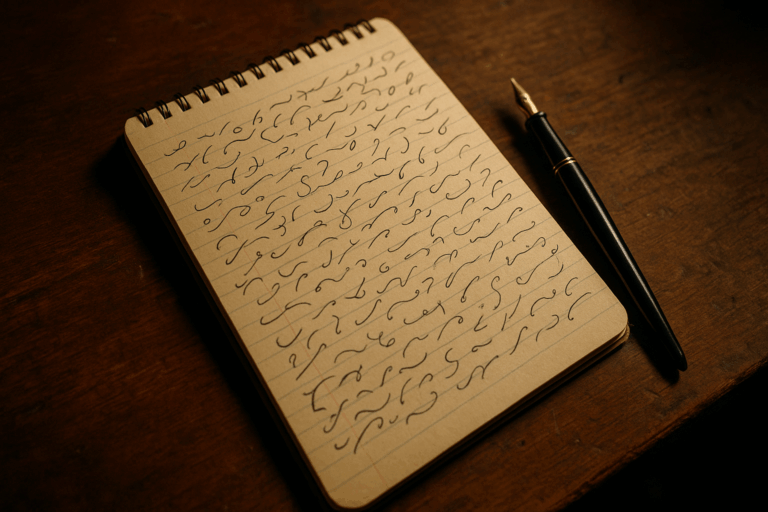

Imagine a packed courtroom in the 1950s. A witness is speaking quickly, lawyers are firing objections, and a judge is issuing rapid-fire rulings. In the corner, a figure hunched over a steno pad is capturing every single syllable. There are no tape recorders, no digital assistants—just a pen, paper, and a mind trained in a cryptic, elegant system of symbols. This was the world of the stenographer, a world built on the lost art of shorthand.

Today, when we think of fast writing, we think of autocorrect and flying thumbs on a smartphone. But for over a century, the peak of writing efficiency was a silent, graceful dance of lines, hooks, and curves. Shorthand isn’t just messy handwriting; it’s a family of sophisticated writing systems, or stenographies, designed to do the impossible: write at the speed of human speech. To understand its genius, we need to look beyond the squiggles and into its clever linguistic core.

The Linguistic Engine: Why Shorthand is So Fast

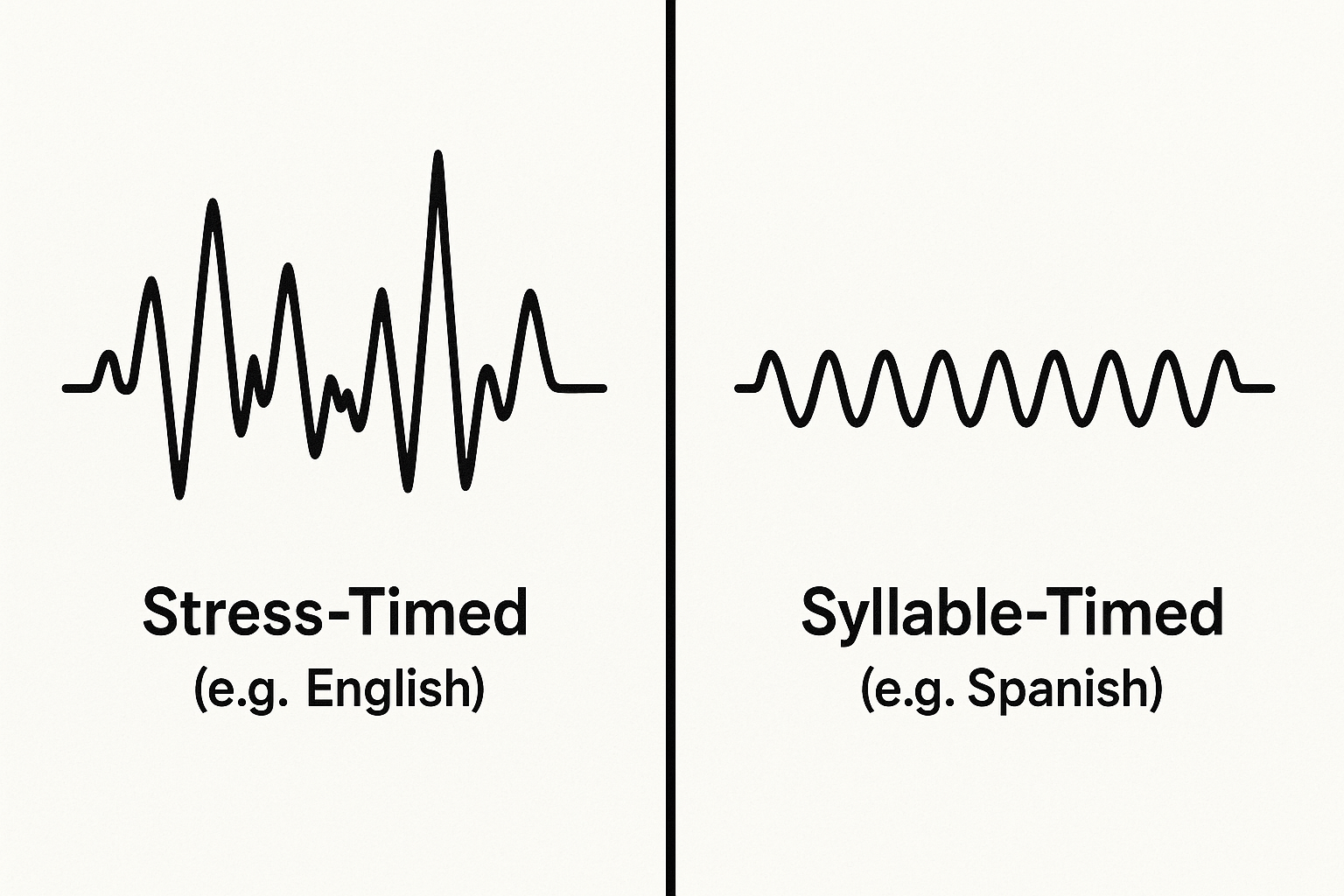

Standard writing, or longhand, is notoriously inefficient. It’s a system designed for clarity, not speed. We write “though,” “through,” and “tough” with the same four letters—”ough”—that represent three completely different sounds. Shorthand systems throw this inefficiency out the window. They operate on a simple, revolutionary principle: write what you hear, not what you spell.

This phonetic approach is the first key to its speed. Shorthand is a language of sounds. The silent ‘k’ in “know,” the phantom ‘b’ in “doubt,” and the entire “e-a-u” in “bureau” are simply ignored. By stripping words down to their phonetic components, a writer saves precious time and ink. But this is just the beginning of its linguistic alchemy.

Geometric Simplicity and the Logic of Strokes

Shorthand systems are built from a minimalist’s toolkit. Instead of the complex, multi-stroke letters of our alphabet (think ‘G’, ‘B’, ‘k’), shorthand uses the simplest possible marks: straight lines, shallow curves, deep curves, circles, and hooks. Each mark is assigned to a consonant sound based on linguistic principles. The two most dominant systems in the English-speaking world, Pitman and Gregg, showcase this beautifully.

Pitman Shorthand, invented by Sir Isaac Pitman in 1837, is a geometric system. Its brilliance lies in how it pairs sounds. Voiceless consonants (like ‘p’, ‘t’, ‘ch’) are written with a light stroke. Their voiced counterparts (‘b’, ‘d’, ‘j’) are written with the exact same stroke, only shaded or thickened. Instantly, a core linguistic feature—voicing—is encoded with a simple change in pressure.

- A light, short stroke represents /p/.

- A heavy, short stroke represents /b/.

- A light, slanted stroke represents /t/.

- A heavy, slanted stroke represents /d/.

Gregg Shorthand, created by John Robert Gregg in 1888, took a different approach. It’s a cursive, flowing system based on the ellipse. Gregg eliminated shading, which could be cumbersome with fountain pens, and instead differentiated sounds by the length of the stroke. Vowels are represented by small and large circles and hooks written directly within the word, making the outlines incredibly fluid and compact.

The Art of Abbreviation and Phrasing

Beyond the phonetic alphabet, shorthand achieves its incredible speeds through systematic abbreviation. This operates on several levels:

- Brief Forms (Logograms): The most common words in the language (“the,” “a,” “is,” “of,” “to”) are reduced to a single, simple symbol. For example, in Gregg, a tiny slanted tick represents “a” or “an,” while a small forward curve represents “is” or “his.” This is essentially a logographic system embedded within a phonetic one.

- Abbreviating Principle: Longer, less common words are shortened by applying logical rules, often by omitting medial vowels or weak consonants. “Business” might become the equivalent of “bsns,” and “government” might become “gvmt.”

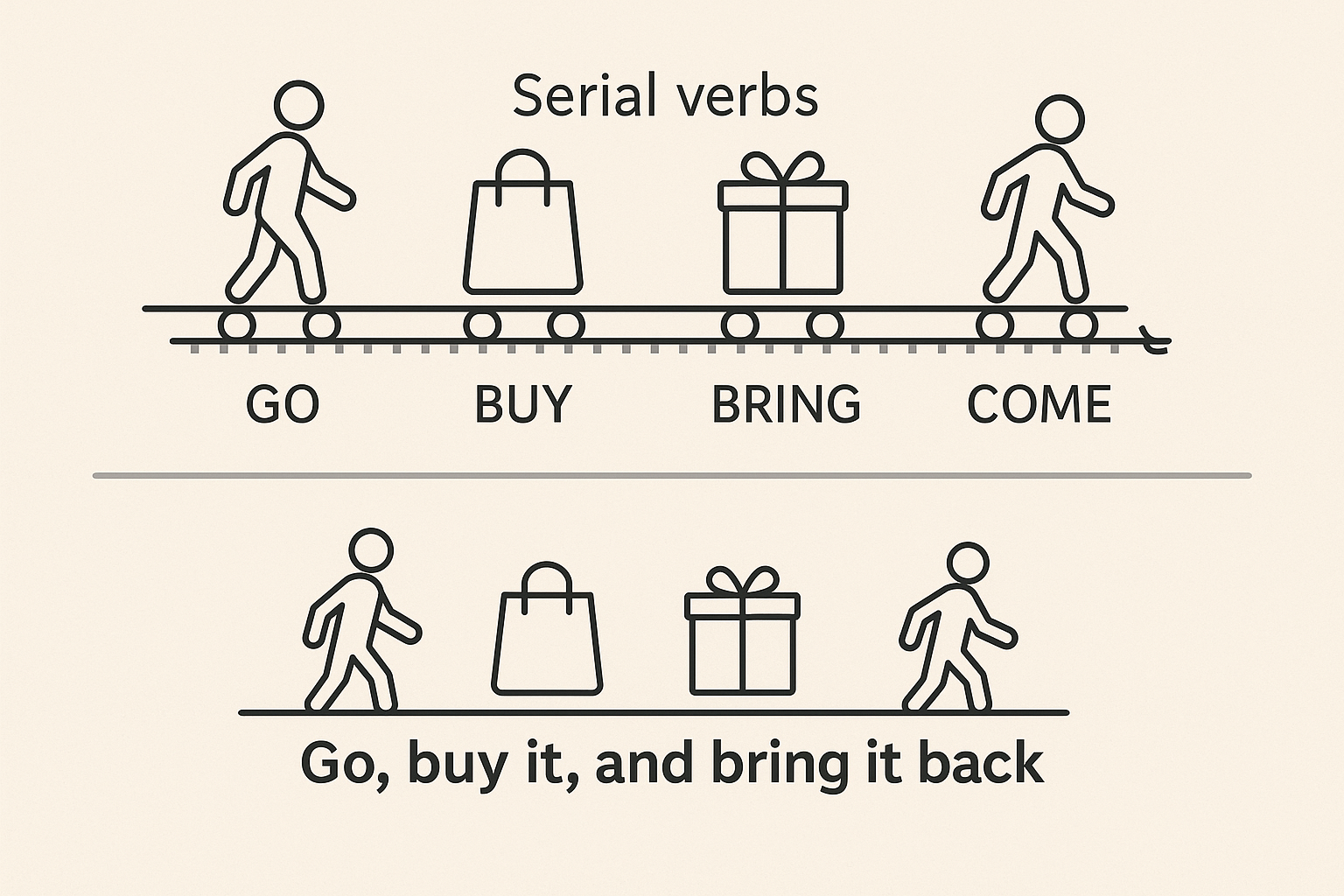

- Phrasing: This is perhaps the most elegant feature of advanced shorthand. Instead of writing words one by one, stenographers join common word combinations into a single, uninterrupted outline. Pen lifts are the enemy of speed. A phrase like “I will be” or “it is of the” becomes one fluid motion, blending the symbols for each word into a single, graceful form. This requires the writer to think in phrases, not just words, further bridging the gap between thought and transcription.

A Tale of Two Systems: Pitman vs. Gregg

While hundreds of shorthand systems have existed, Pitman and Gregg dominated the 20th century. Their philosophical differences highlight the diverse ways of solving the problem of speed writing.

Pitman: The Geometric & Precise

Often considered more precise but with a steeper learning curve, Pitman relies on three core elements: geometry, shading, and position. The position of a symbol—written above, on, or through the ruled line of a steno pad—indicates the main vowel sound in the word. This makes Pitman’s outlines incredibly information-dense, but it requires great accuracy from the writer.

Gregg: The Flowing & Elliptical

Gregg was marketed as easier to learn and, for many, faster to write. By eliminating shading and positional writing, it removed two major hurdles. Its beauty lies in its cursive motion, which mimics the natural flow of handwriting. All writing stays on the line, and vowels are integrated into the outlines, creating a system that prioritizes momentum and forward flow above all else.

The Stenographer: More Than a Scribe

The art of shorthand wasn’t just in the system; it was in the human processor. A professional stenographer running at 200 words per minute was performing an astonishing cognitive feat. They had to:

- Listen to and comprehend speech in real-time.

- Mentally break down the speech into its phonetic components.

- Translate those sounds into the correct shorthand symbols, applying rules of abbreviation and phrasing on the fly.

- Execute those symbols on paper with muscular precision.

This high-speed linguistic conversion is a testament to the brain’s plasticity and the power of a well-designed writing system. The steno pad, with its iconic vertical line down the middle, was their canvas, allowing for short, efficient lines of writing.

The Echo of a Lost Language

In an age of instant audio and video recording, the practical need for manual shorthand has all but vanished. Court reporters now use stenotype machines, a form of “machine shorthand” that allows for even greater speeds and real-time digital transcription. Yet, the legacy of pen shorthand endures.

It stands as a beautiful monument to human ingenuity—a solution born from the need to make the ephemeral spoken word permanent. The linguistic principles behind Pitman and Gregg reveal a deep understanding of phonetics, frequency, and ergonomics. It’s a forgotten language not of a foreign country, but of a different time—a time when the speed of the hand, guided by a sharp mind, was the ultimate tool of record. It reminds us that long before our digital tools, we created our own “software” for the mind, written in a language of speed.