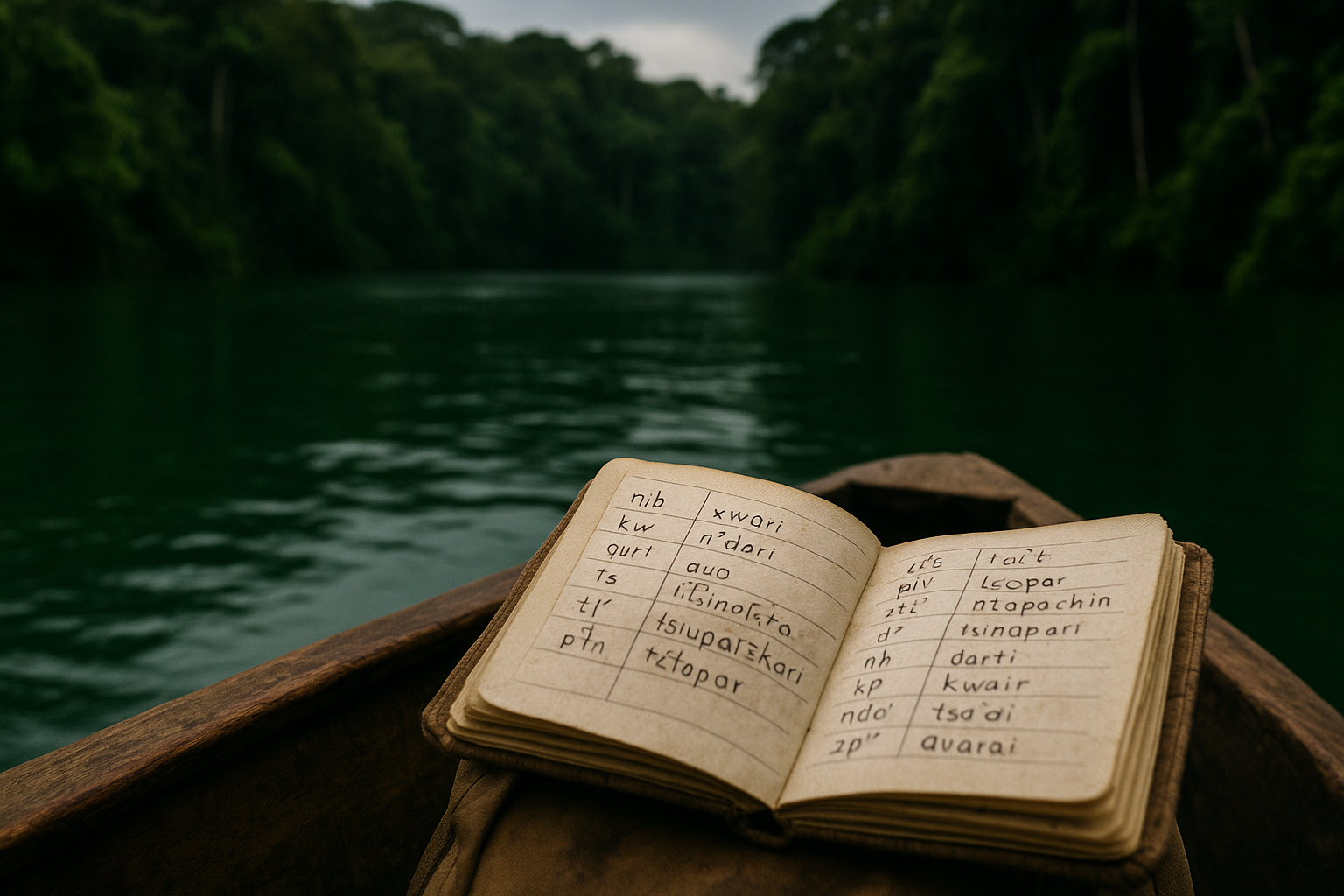

Imagine paddling a canoe down the Maici River, a winding tributary deep within the Brazilian Amazon. The air is thick, the sounds of the jungle are a constant symphony, and you are about to make contact with a small, isolated tribe of a few hundred people: the Pirahã. This was the world of Daniel Everett, a man who went into the rainforest as a Christian missionary in the 1970s with the goal of translating the Bible. He emerged decades later, having lost his faith but found something far more paradigm-shattering: a language that seemed to break all the rules of human communication.

Everett’s work with the Pirahã people would ignite one of the most explosive and enduring controversies in modern linguistics, pitting him directly against the field’s most towering figure, Noam Chomsky. At stake was not just the structure of one obscure language, but the very foundation of how we understand the human mind.

The Universal Blueprint for Language

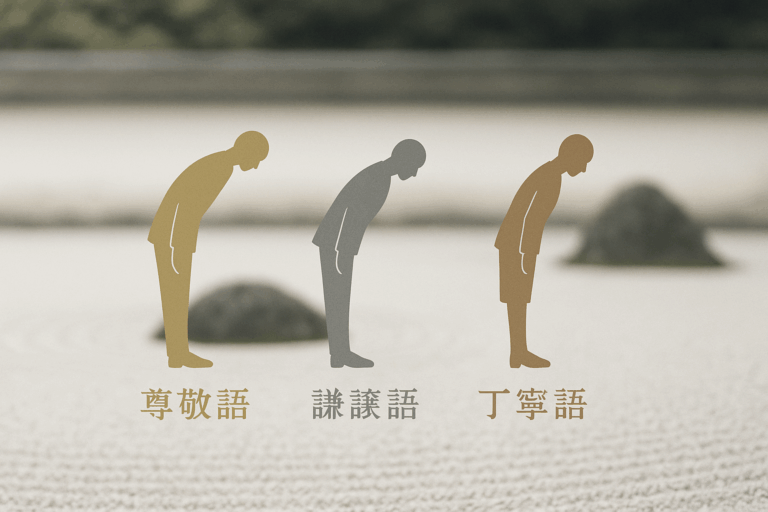

To grasp the scale of the controversy, we first need to understand the theory that Everett’s claims threatened. For over half a century, the dominant theory in linguistics has been Noam Chomsky’s Universal Grammar (UG). Chomsky proposed that all humans are born with an innate, hard-wired “language organ” in the brain. This organ contains a universal blueprint—a set of grammatical rules and principles common to all 7,000-plus human languages.

This explains why children can learn a language so quickly and with such incomplete information. They aren’t starting from scratch; they are simply filling in the specific parameters of the language they hear around them, like setting switches on a pre-built machine.

At the heart of Universal Grammar, Chomsky later argued, lay a single, powerful mechanism: recursion.

Recursion is the ability to embed a phrase or clause inside another phrase of the same type. It’s what allows us to create infinitely long and complex sentences from a finite set of rules.

Think about it:

- “This is the cat.” (Simple)

- “This is the cat that chased the rat.” (One level of embedding)

- “This is the cat that chased the rat that ate the cheese.” (Two levels)

You can also see it in possessives (“My friend’s mother’s car”) or nested thoughts (“He thinks that she knows that I am here”). For Chomsky, recursion wasn’t just a feature of language; it was the feature. It was the “great leap forward” in human evolution that separated our cognitive abilities from all other animals.

The Pirahã Anomaly: A Language That Lives in the Now

As Daniel Everett spent years, then decades, living with and documenting the Pirahã, he began to notice that their language was not just different—it was radically different. It seemed to be missing features that linguists had long considered fundamental to all languages.

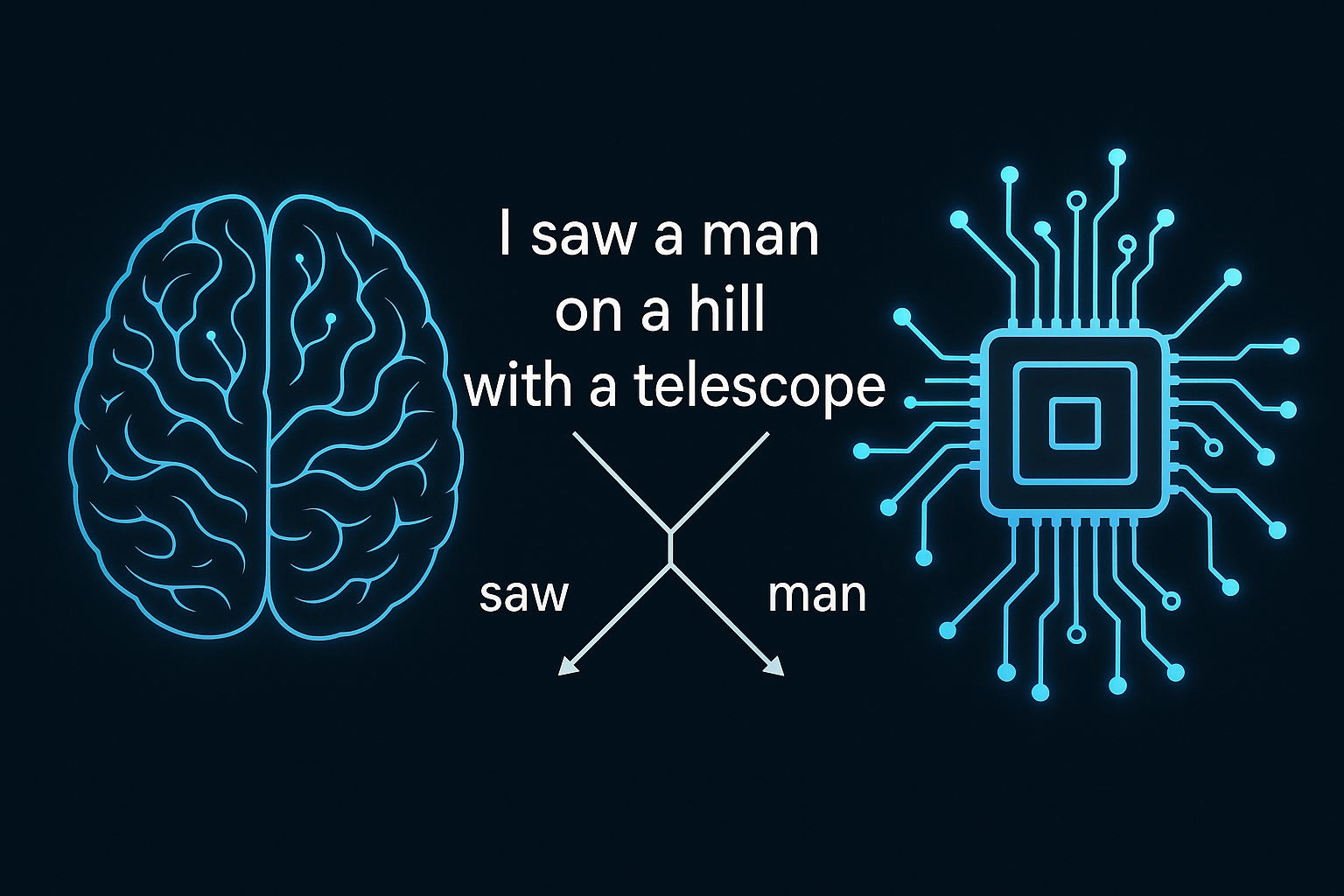

Most controversially, Everett claimed that Pirahã completely lacks recursion. They simply do not embed clauses within other clauses. Instead of saying, “I want you to make me an arrow,” a Pirahã speaker would say two separate sentences: “I want a thing. You make an arrow.” Instead of “The man’s brother’s house is big,” they would say, “The man has a brother. The brother has a house. The house is big.”

But the strangeness didn’t stop there. Everett documented a cluster of other “missing” features:

- No fixed color words: They describe colors using comparisons, like “blood-like” for red or “immature-leaf-like” for green.

- No numbers or counting system: They have words for “about one” (hói) and “many” (hoí), but no way to say “two” or “ten.”

- The simplest kinship system known: They have no specific words for “aunt,” “uncle,” or “cousin.”

- No creation myths or long-form oral history: Their stories are grounded in the living memory of the people present.

Everett argued that these linguistic oddities were not random. They were all consequences of a single, powerful cultural constraint he called the Immediacy of Experience Principle. The Pirahã culture, he claimed, is intensely focused on the here-and-now. They only speak about things they have either personally witnessed or heard about from a direct, living witness. This cultural value, Everett proposed, shaped their language, stripping it of the need for complex structures that could describe abstract concepts, hypothetical situations, or events in the distant past or future.

The Linguistic Firestorm

Everett’s 2005 paper, “Cultural Constraints on Grammar and Cognition in Pirahã,” landed like a bombshell. If he was right, Pirahã was a direct counter-example to Universal Grammar. A language without recursion meant that recursion could not be the universal, innate foundation of all human language. It would suggest that language is not a biological organ but a cultural tool, shaped by the specific needs and values of its speakers.

The backlash from the Chomskyan school of linguistics was immediate and fierce. The critiques fell into several camps:

- Everett is simply wrong: Some critics, after analyzing Everett’s own data, claimed to find evidence of recursion that he had missed. This remains a point of intense technical debate.

- Performance vs. Competence: Chomskyans argue there’s a difference between what a language can do (competence) and how people happen to use it (performance). They suggested the Pirahã might have the cognitive capacity for recursion but, for cultural reasons, simply choose not to use it. For them, this doesn’t disprove UG, as the underlying “machinery” is still there.

- Ad hominem attacks: The debate became personal. Chomsky famously called Everett a “charlatan,” while Everett accused the Chomskyan framework of being a “failed research program” that ignored inconvenient data from the field.

What a Tiny Tribe Teaches Us About Our Minds

The Pirahã controversy is more than just an academic squabble. It forces us to ask profound questions about the relationship between language, culture, and thought.

If Everett is right, it lends support to a modern version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis—the idea that the language you speak influences the way you think. The Pirahã’s culture of “immediacy” may have shaped a language without recursion, which in turn reinforces a way of thinking that is firmly grounded in concrete, observable reality. It suggests that culture is the architect of grammar, not the other way around.

If Chomsky is right, our fundamental linguistic ability is a universal biological endowment, a part of our human birthright. Cultural variations are just surface-level decorations on a deep, shared cognitive structure.

Today, the debate is far from settled. Linguists continue to argue, re-analyze data, and plan new fieldwork. But the story of Daniel Everett and the Pirahã remains a powerful testament to the value of stepping outside the lab and into the world. It’s a reminder that deep in the world’s most remote corners, a small group of people speaking a unique tongue can challenge our most fundamental assumptions about who we are and what it means to be human.