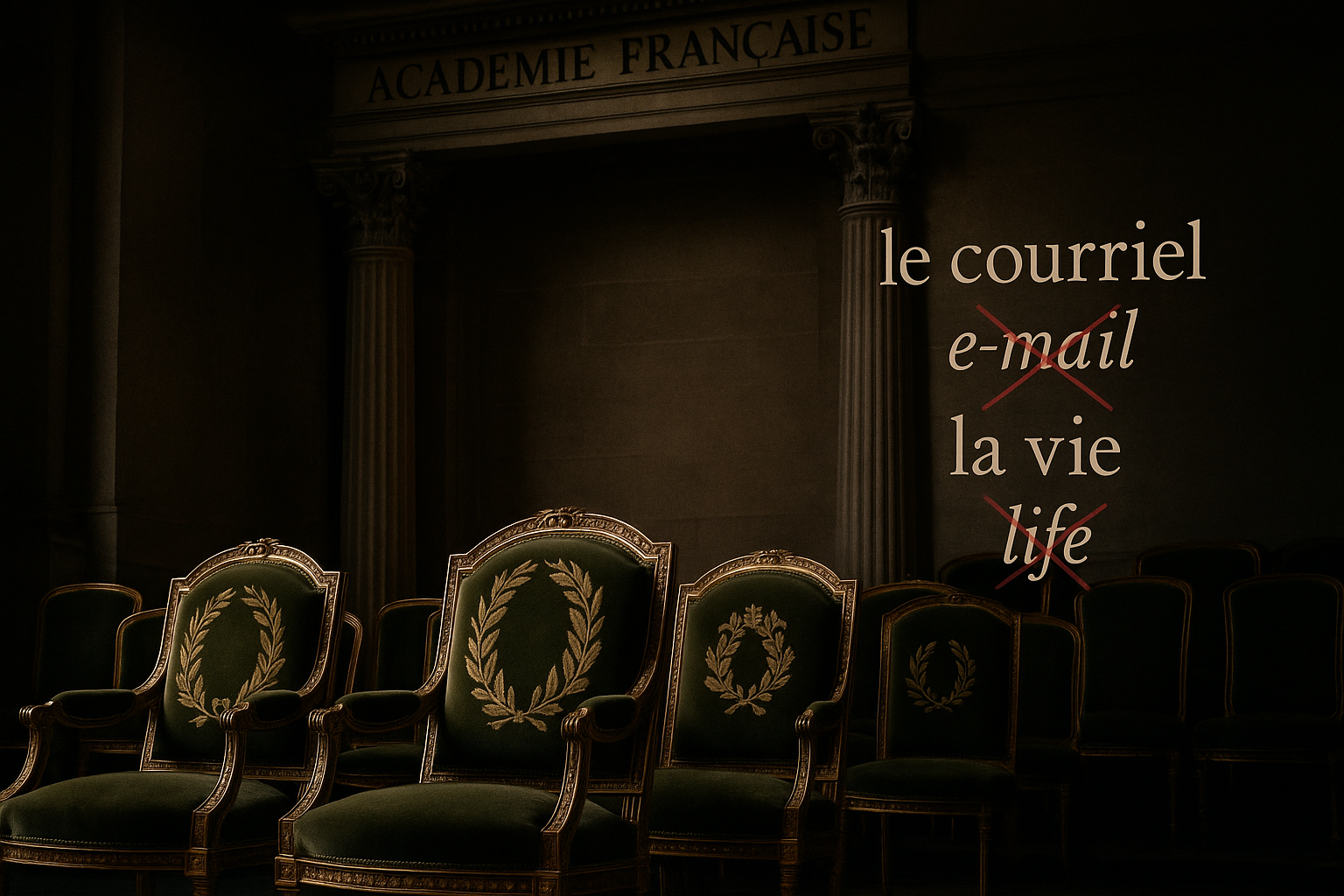

In the heart of Paris, housed within the stately Palais de l’Institut de France, a unique battle is being waged. It’s not a fight with swords or cannons, but with words and dictionaries. This is the home of the Académie Française, a 400-year-old institution whose forty members, known as les immortels (“the immortals”), are charged with an immense task: to protect and perfect the French language. In an age of hashtags, memes, and the relentless creep of English, their mission has never been more contentious or fascinating.

A Royal Mandate for Linguistic Order

To understand the Académie, we must travel back to 1635. France, under the rule of King Louis XIII, was a patchwork of regional dialects. His chief minister, the formidable Cardinal Richelieu, envisioned a unified, powerful nation, and he understood that a unified language was key to that vision. He established the Académie Française with a clear mission: “to give certain rules to our language and to render it pure, eloquent, and capable of treating the arts and sciences.”

Their primary task was to create a dictionary that would serve as the ultimate arbiter of “proper” French (le bon usage). This wasn’t just a list of words; it was a political and cultural project. By standardizing French, Richelieu aimed to elevate it above other European languages, making it the premier language of diplomacy, literature, and intellectual thought—a role it would hold for centuries.

The Forty Immortals and the Dictionary of Ages

The Académie is composed of forty members, elected for life by their peers. These “immortals”—a nickname derived from their motto, “À l’immortalité” (To immortality)—are typically distinguished writers, poets, scholars, and sometimes even former politicians or scientists. Over the centuries, their ranks have included giants like Voltaire, Victor Hugo, and Louis Pasteur. Their lifetime appointment is meant to ensure their independence and dedication to the long-term health of the language.

Their central work remains the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française. If you think dictionary-making is a quick process, think again. The Académie moves at a glacial pace. The first edition was published in 1694, a full 59 years after its founding. Today, they are still working their way through the ninth edition, which began in 1992!

The process is meticulous. A special dictionary commission meets weekly to examine words, one by one. They debate definitions, semantic nuances, and whether a new word has proven its worth and staying power. Their goal is not to capture every slang term or fleeting trend, but to codify words that have become a stable and accepted part of the French linguistic landscape. This inherently conservative approach is both the Académie’s greatest strength and its most criticized weakness.

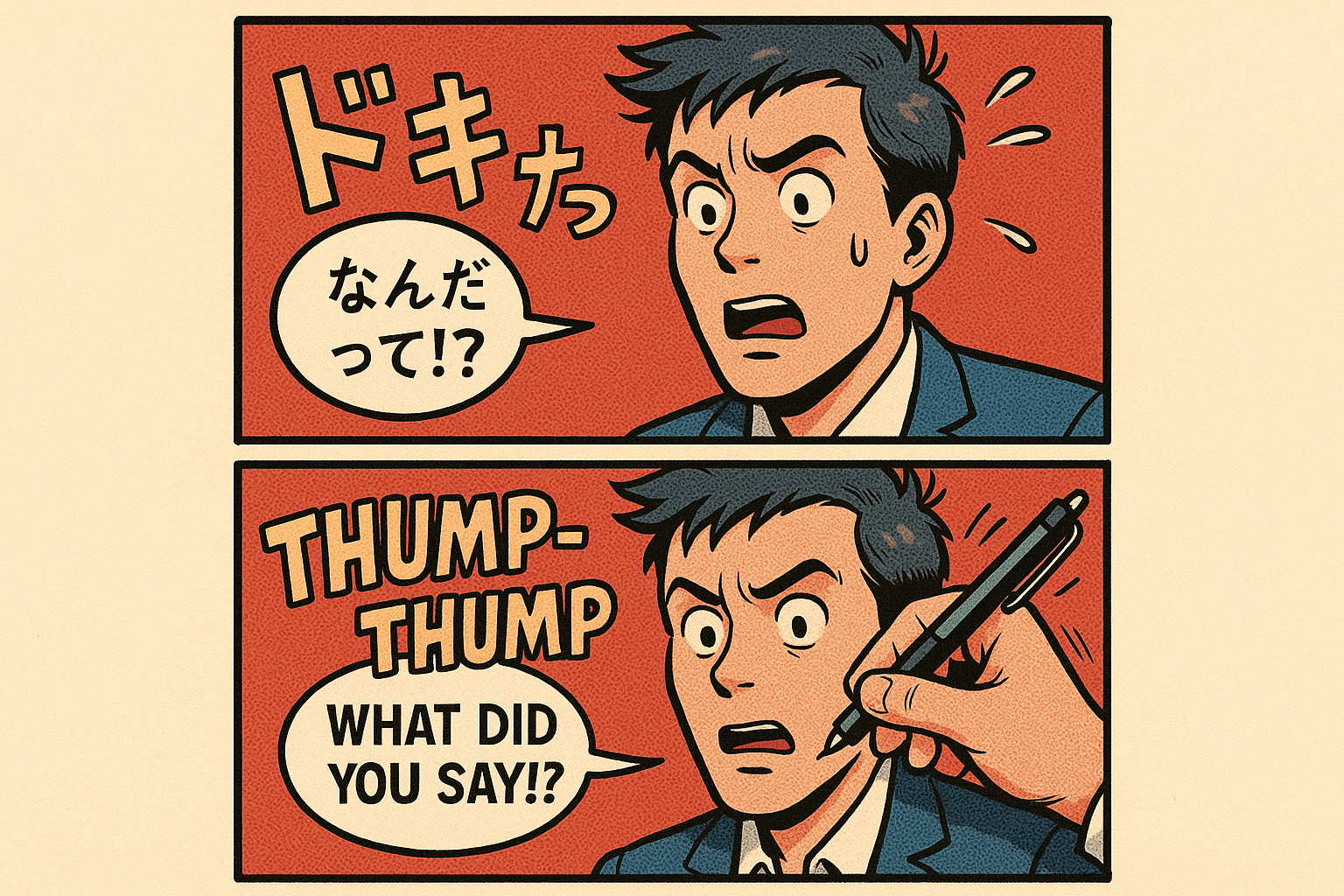

The Modern Battlefield: Le Franglais

While the dictionary is a monumental task, the Académie’s most public-facing battle today is against the influx of English words, a phenomenon pejoratively dubbed le franglais. Globalization, technology, and American cultural dominance have unleashed a firehose of English terminology into everyday French.

Walk down a street in any French city, and you’ll hear it:

- People go out for le weekend.

- They find a spot in le parking.

- Businesspeople talk about le marketing and le brainstorming.

- They listen to un podcast and post on social media with un hashtag.

The Académie does not simply rail against these terms from its ivory tower. Instead, it practices a form of linguistic intervention. Its members and committees actively research and propose native French alternatives. Their goal is to offer a French word that is just as clear and useful as the English import.

The results of this campaign have been mixed, creating a fascinating case study in linguistic adoption:

- Success Story: Courriel was proposed as an alternative to “e-mail” (a blend of courrier électronique). It has been widely adopted in official contexts and is understood by most French speakers.

- A Notable Attempt: For “spoiler,” the Académie championed the neologism divulgâcher, a clever portmanteau of divulguer (to divulge) and gâcher (to spoil). It has gained significant traction, especially among a younger, internet-savvy crowd.

- The Losing Battles: Many recommendations fail to stick. The public largely ignores accès sans fil à l’internet in favor of the simple le Wi-Fi. Likewise, mot-dièse (literally “sharp-word,” from the musical symbol #) has been thoroughly defeated by le hashtag.

Prescriptivism vs. Descriptivism: A War of Ideology

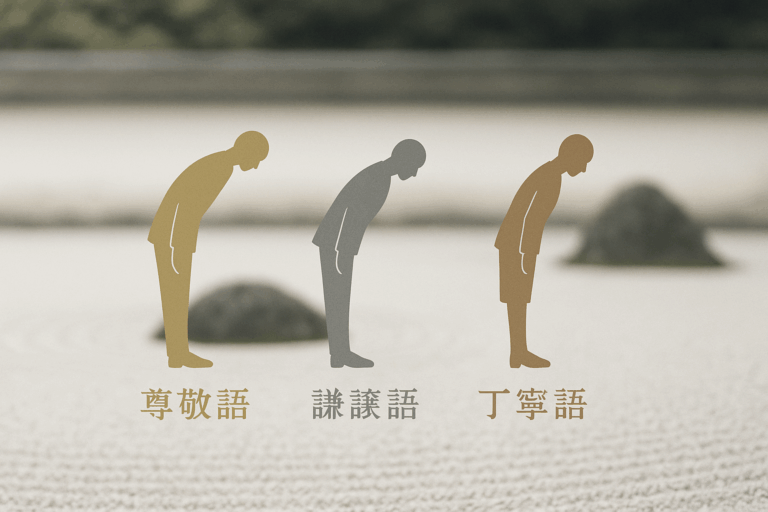

The work of the Académie Française places it squarely on one side of a fundamental linguistic debate: prescriptivism versus descriptivism.

Linguistic prescriptivism, the Académie’s philosophy, asserts that there is a “correct” way to use a language. It aims to prescribe rules and norms, often with the goal of preserving clarity, elegance, or tradition. It is an act of curation.

Linguistic descriptivism, the dominant view among modern linguists, argues that the role of a linguist is to describe how language is actually used by its speakers, without judgment. From this perspective, if millions of French people say “le weekend,” then “le weekend” is a part of the French language. Language is seen as a living, evolving entity shaped by its speakers, not by a committee.

Critics label the Académie as elitist, out of touch, and fighting an unwinnable war against the natural evolution of language. They argue that language change is normal and that loanwords have enriched languages for millennia (after all, English itself is full of French words like government, jury, and art).

However, the Académie and its defenders see their role as that of a cultural guardian. They are not just preserving grammar; they are preserving a cultural heritage. For them, allowing a deluge of English words to replace perfectly good French ones is a form of linguistic and cultural erosion. They fight for the “genius” of the French language—its specific structure, its sounds, and its spirit.

Whether you view the Académie Française as a vital cultural bastion or an anachronistic relic, its story is a compelling look at the intersection of language, politics, and identity. It reminds us that language is more than just a tool for communication; it is a repository of history, a symbol of culture, and a battleground for ideas. And on the banks of the Seine, the forty immortals continue their centuries-long watch, fighting for the soul of their beloved tongue.