In the golden light of a summer afternoon, a honeybee returns to her hive, her body a vessel of vital information. She begins a strange, silent ritual: a dance. She waggles her abdomen, turns in a figure-eight, and repeats. This is no random jig; it’s a precise, symbolic message telling her sisters the exact direction and distance to a rich field of flowers. It’s an act of communication so sophisticated it forces us to ask a profound question: Do animals have language?

The answer, most linguists would argue, is a fascinating “no.” While the animal kingdom is bursting with incredible systems of communication, human language possesses a few unique properties that set it apart. To understand the difference, we need to move beyond the simple idea of “communication” and look at the specific design features that make human language a unique phenomenon.

The Linguist’s Checklist: What Makes a Language?

When linguists talk about “language,” they’re referring to a system with a very specific set of characteristics. While there are many, a few key properties, heavily influenced by linguist Charles Hockett’s work, form the core of the debate. Think of it as a checklist for “true language”:

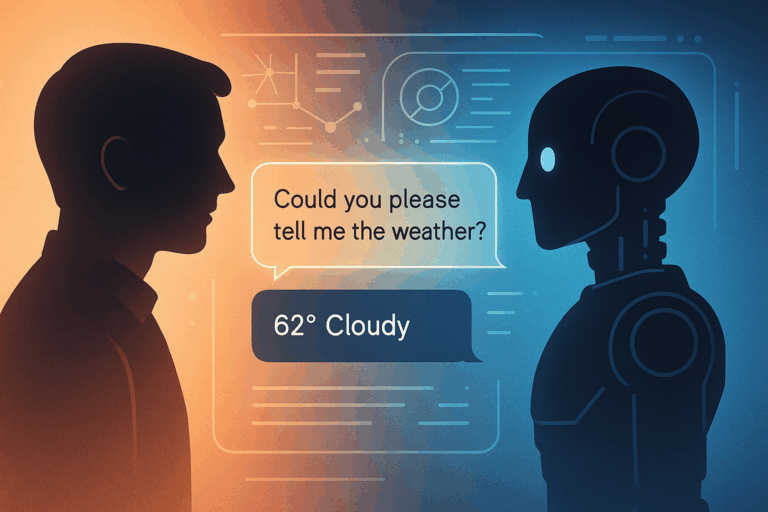

- Displacement: The ability to talk about things that are not present in the here and now. This includes the past, the future, hypothetical situations, or things that exist only in our imagination (like unicorns or political theories).

- Productivity (or Generativity): The ability to create and understand an infinite number of novel utterances from a finite set of rules and words. You can form a sentence that has never been spoken before in the history of the world, and other speakers will understand it.

- Duality of Patterning: This is a two-level system. At the first level, we have a small number of meaningless sounds (phonemes), like /k/, /æ/, and /t/. At the second level, we combine these meaningless sounds to create a vast number of meaningful units (words), like “cat,” “act,” and “tack.”

- Arbitrariness: The relationship between a word and what it represents is arbitrary. The word “tree” doesn’t look, sound, or feel like a tree. The connection exists only by social convention.

With this checklist in hand, let’s examine some of the most advanced communicators in the animal kingdom.

Case Study 1: The Grammar of the Honeybee

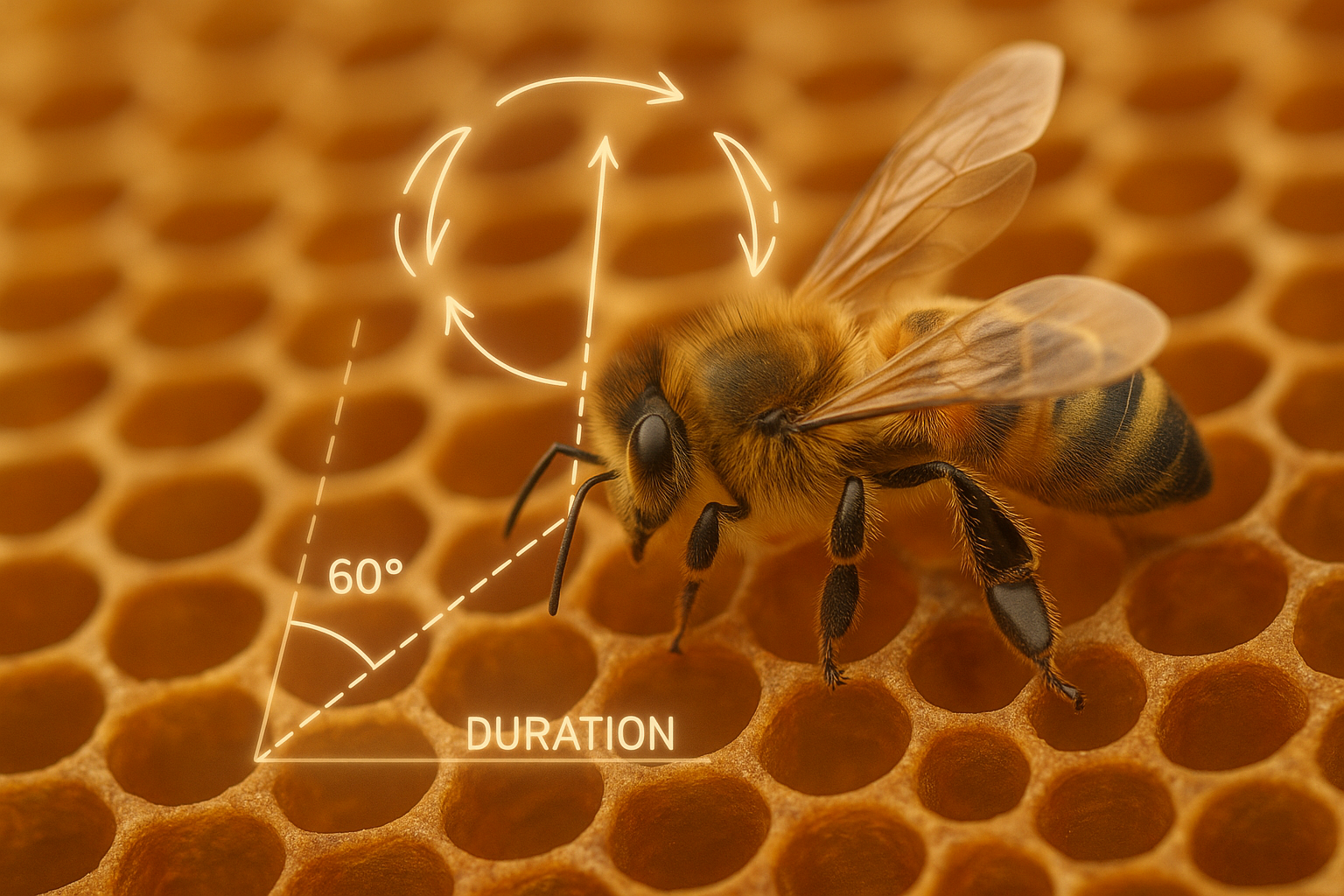

Karl von Frisch won a Nobel Prize for deciphering the honeybee’s “waggle dance,” and for good reason. It’s a marvel of symbolic communication. The angle of the bee’s dance relative to the sun’s position in the sky indicates the direction of the food source. The duration of the “waggle” part of the dance indicates the distance.

How does it fare against our checklist?

The waggle dance exhibits stunning displacement. The bee is communicating about a patch of flowers miles away, something not immediately present to her audience. This is a remarkable, language-like feature.

However, it falls short on productivity. A bee can indicate “nectar 2 miles north” or “pollen 1.5 miles northeast,” but she cannot create a new type of message. She can’t say, “The blue flowers are safer than the yellow ones because a spider has built a web there.” The topics are completely closed; they are always about the location and quality of resources. There’s no way to combine elements to create a fundamentally new idea.

There is also no duality of patterning. The dance is a holistic signal. An individual wiggle or turn doesn’t function like a meaningless sound that can be recombined to form different “words.”

Verdict: An incredibly sophisticated system of communication with displacement, but not a language.

Case Study 2: The Prairie Dog Sentinel

Dr. Con Slobodchikoff’s research on the alarm calls of Gunnison’s prairie dogs has revealed a system of shocking specificity. Prairie dogs don’t just have a generic call for “danger.” They have distinct calls for different predators: coyotes, hawks, badgers, and humans.

Even more impressively, their calls can contain descriptive information. By analyzing the acoustic properties of the calls, Slobodchikoff found that they can encode features like the color of a human’s shirt, whether a person is tall or short, and even distinguish between a human carrying a rifle versus one carrying a tripod. They seem to have different “words” for things and can combine them into phrases, such as [coyote] + [approaching quickly].

This system clearly shows arbitrariness; the sound for “hawk” doesn’t sound like a hawk. It also demonstrates a rudimentary form of productivity, or what some might call “semanticity.” They can combine elements to describe novel situations, like a “tall human in a blue shirt.”

The main limitation is displacement. Prairie dogs are almost always reacting to a present threat. They aren’t sitting in their burrows at night discussing the coyote that almost got them last Tuesday. Their communication is firmly rooted in the immediate context.

Verdict: Perhaps the closest thing to a lexicon and basic syntax in the animal world. But its lack of displacement and the limited scope of its productivity keep it in the realm of complex communication, not language.

Case Study 3: The Enigmatic Songs of the Whale

The haunting, complex songs of the humpback whale are another source of fascination. These songs aren’t random; they have a clear hierarchical structure. Individual sound units combine to form phrases; phrases are arranged into themes; and themes are repeated in a sequence to form a song. This nested, rule-governed structure is tantalizingly similar to human syntax.

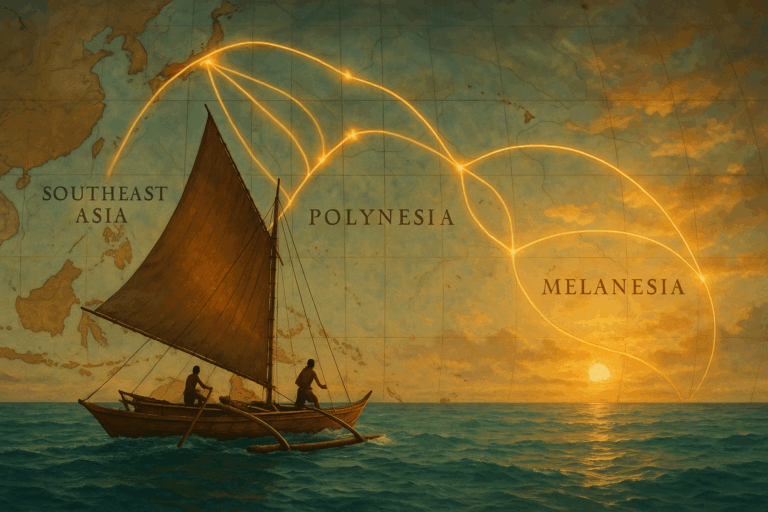

Furthermore, these songs are culturally transmitted. Whales in one region sing the same song, but that song evolves over months and years. Sometimes, a whole population will abandon their current song to adopt a new, “hit” song they heard from a neighboring population.

The great mystery with whales is semantics. We can identify the structure—the “grammar” of their songs—but we have almost no idea what, if anything, it means. Is it a mating display? A territorial claim? Or are they conveying specific information about migration routes, food sources, or their history?

Without understanding the meaning, we can’t test for displacement or productivity. Do their songs recount past journeys? Do they invent new “stanzas” to describe a new phenomenon, like the sound of a ship’s engine? We simply don’t know.

Verdict: Whales show compelling evidence for a complex, syntax-like structure, but the semantic code remains unbroken, preventing us from calling it language.

What Divides Communication from Language?

Animal communication systems, however brilliant, are overwhelmingly closed systems. They are designed to convey specific information about a limited set of topics crucial for survival: food, predators, mating, and territory. The waggle dance is only about foraging. The prairie dog’s calls are only about threats.

Human language is an open system. Its hallmark is infinite productivity. There is no limit to what we can talk about. We use language to gossip, tell lies, write poetry, formulate scientific laws, ask questions about the universe, and even to talk about language itself (which is what this article is doing!). This unbounded, creative potential, built upon the foundation of duality of patterning, is what truly separates our system from all others.

To say animals don’t have “language” is not to diminish their intelligence or the richness of their social lives. It is simply a technical distinction. They are masters of communication, perfectly adapted to their worlds. But the evolutionary path that gave humans the ability to combine meaningless sounds into infinite meaningful ideas appears to be a road traveled only once.