If you’ve ever marveled at the word antidisestablishmentarianism, you’ve had a small taste of a linguistic system that many languages around the world use as their fundamental operating principle. In English, we tend to think of words as discrete units. We might add a prefix like “un-” or a suffix like “-able,” but for the most part, we express complex ideas by stringing separate words together: “I will go to the big house.”

But what if you could snap those grammatical ideas—”to,” “the,” “big,” “I,” “will”—directly onto the word “house” itself? Welcome to the world of agglutinative languages, the linguistic equivalent of a master Lego builder’s workshop.

The Lego Principle of Language

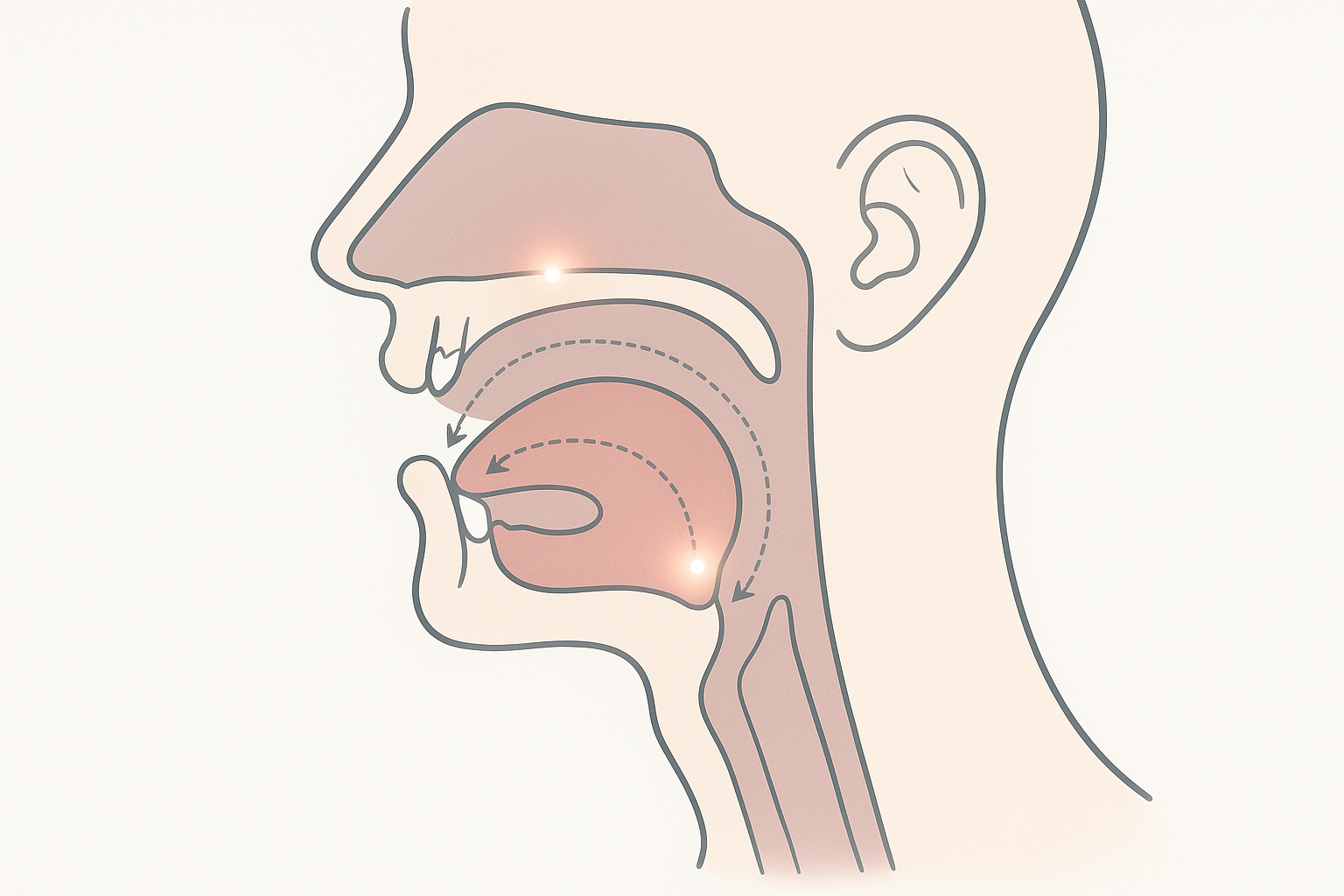

At the heart of agglutination is the morpheme: the smallest unit of meaning in a language. The word “cats” has two morphemes: “cat” (the furry creature) and “-s” (meaning more than one). Agglutinative languages take this principle to the extreme. They build words by stringing together a series of morphemes, each with a single, distinct function, like snapping individual Lego bricks together to create a complex model.

The key features of this system are:

- One Morpheme, One Meaning: Each affix (a prefix, suffix, or infix) typically represents just one grammatical concept. A plural marker is just a plural marker. A past-tense marker is just a past-tense marker.

- Consistency: The morphemes don’t usually change their shape or sound much when they’re attached. The “-s” in “cats,” “dogs,” and “rats” is consistent. Agglutinative languages apply this consistency across a vast array of grammatical functions.

This creates an elegant, transparent, and highly regular system. Once you learn what the “bricks” mean, you can often understand and construct incredibly long words with precision.

Master Builders: The Case of Turkish

Turkish is a quintessential example of an agglutinative language. Its words can grow to staggering lengths, encompassing concepts that would require an entire clause in English. Let’s deconstruct a famous, albeit slightly exaggerated, example to see how it works:

Avrupalılaştıramadıklarımızdan

This behemoth translates to something like, “from among the ones whom we could not make Europeanized.” It looks intimidating, but it’s built with perfect logic, brick by brick, from a simple root.

Avrupa – Europe (the root word)

-lı – with/from a place (making it “European”)

-laş – to become (-ize)

-tır – to cause someone to do something (the causative form)

-a – the negative form of ability (“unable to”)

-ma – a general negation marker (-not)

-dık – a participle (“the one which…”)

-lar – plural (“the ones which…”)

-ımız – our (first-person plural possessive)

-dan – from/of (the ablative case)

Each suffix adds a new layer of meaning without altering the ones that came before it. There’s no guesswork; it’s a clear, sequential construction. While this specific word is more of a linguistic curiosity, shorter constructions like evlerinizden (“from your houses”) are used constantly in everyday speech.

The Finnish Case System: A Place for Everything

Head north to Finland, and you’ll find another agglutinative champion. Finnish is famous for its extensive noun case system. Where English uses prepositions like “in,” “on,” “to,” “from,” and “with,” Finnish simply snaps a suffix onto the end of a noun.

Let’s take the word talo, meaning “house,” for a spin:

- talossa – “in the house” (inessive case)

- talosta – “from the house” (elative case)

- taloon – “into the house” (illative case)

- talolla – “on the house” (adessive case)

- talolta – “from on the house” (ablative case)

- taloksi – “into a house / to become a house” (translative case)

This isn’t just a party trick. It allows for incredible precision. You can then stack more morphemes on top. For instance, you can add a possessive suffix and a plural marker: taloissani breaks down into talo (house) + -i- (plural) + -ssa- (in) + -ni (my), giving you “in my houses” in a single, efficient word.

Beyond Europe: Swahili’s Prefabricated Verbs

Agglutination is a global phenomenon. In East Africa, the Bantu language Swahili demonstrates a different flavor of the same principle, relying heavily on prefixes. Swahili verbs are masterpieces of information packing, incorporating the subject, tense, and object all before you even get to the verb’s root.

Consider the simple, beautiful phrase: Ninakupenda (“I love you”).

Ni- – I (subject marker)

-na- – present tense marker

-ku- – you (object marker)

-penda – love (the verb root)

Let’s try a more complex one: Hawatanisomea (“They will not read for me”).

Ha- – negation marker

-wa- – they (subject marker)

-ta- – future tense marker

-ni- – me (object marker)

-som- – read (the verb root)

-ea – an applicative suffix, meaning “for” or “to” the benefit of someone

Just like with Turkish and Finnish, once you learn the parts, you can assemble and disassemble these verbal constructions with ease.

The Other Side: Fusional Languages

To truly appreciate the Lego-like clarity of agglutination, it helps to see the alternative. Many Indo-European languages, like Spanish, Russian, and Latin, are fusional (or inflectional). In these languages, a single affix often “fuses” multiple meanings together into one inseparable package.

Take the Spanish verb hablo (“I speak”). The -o ending tells you three things at once:

- The subject is first-person singular (“I”).

- The tense is present.

- The mood is indicative (a statement of fact).

You can’t break the -o into smaller pieces for “I” and “present tense.” It’s a single, multi-purpose brick. This system is efficient in its own way, but it lacks the transparent, one-to-one mapping of morpheme-to-meaning that defines agglutinative languages.

More Than Just Long Words

Exploring the world’s Lego languages reveals a profound truth about human communication: there are many ways to build a bridge of meaning. Agglutination isn’t inherently more or less complex than the systems English or Spanish speakers use; it’s just a different architectural style. It prioritizes regularity and transparency, creating a grammar that, once mastered, functions with the beautiful logic of a well-sorted box of bricks. Each piece has its place, and together, they can build worlds.