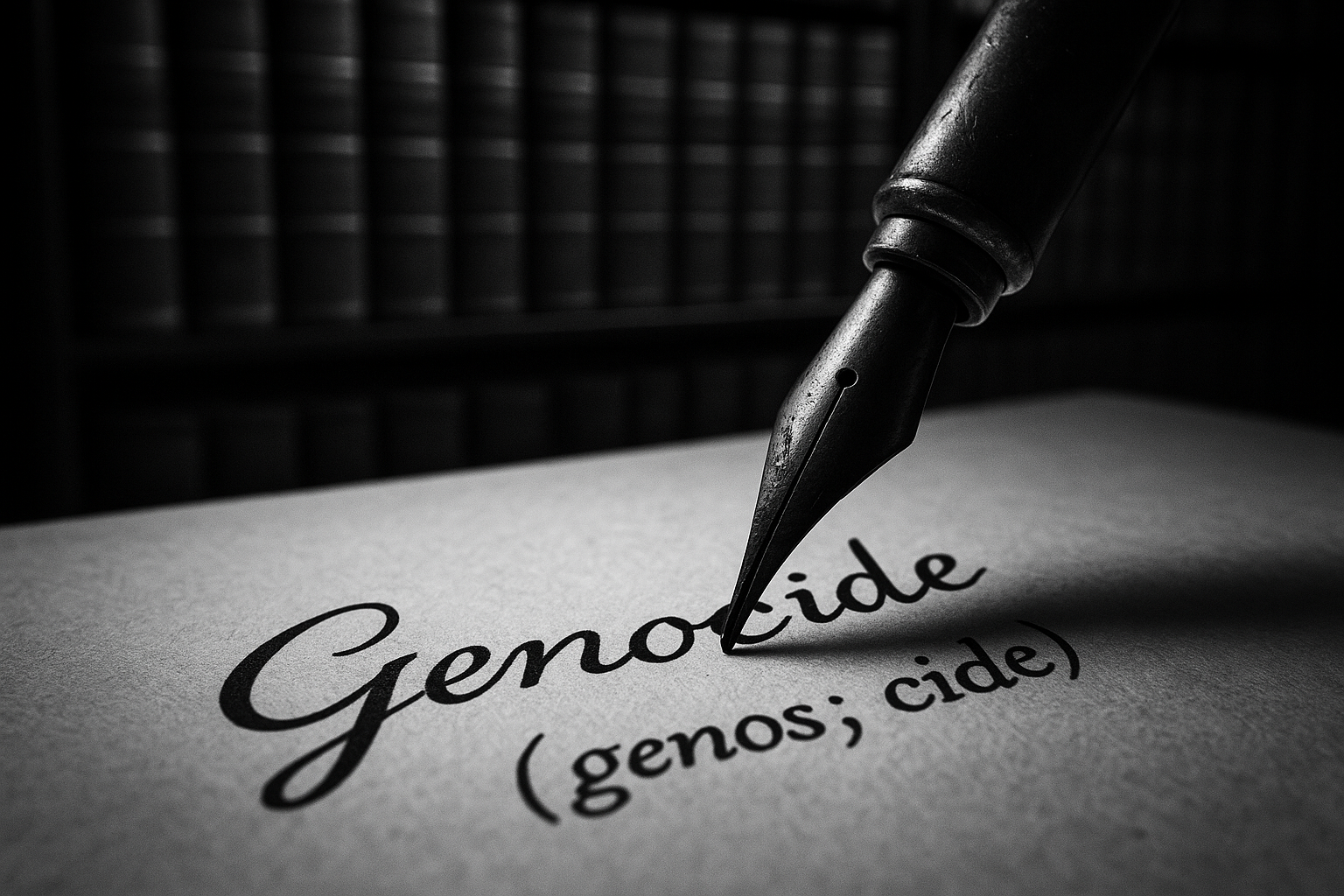

Words are the architecture of our understanding. They give shape to our thoughts, structure to our laws, and voice to our deepest convictions. But what happens when we face a horror so vast, so systematic, that no existing word seems adequate? What do you call the deliberate annihilation of an entire people? Until the mid-20th century, humanity lacked a specific term for this ultimate crime. There was only a devastating, echoing silence. This is the story of how one man, a Polish-Jewish lawyer named Raphael Lemkin, filled that silence by building a word from the rubble of ancient languages: genocide.

The Crime Without a Name

Raphael Lemkin’s life was defined by the observation of systematic destruction. As a young law student in the 1920s, he became deeply troubled by the accounts of the Ottoman Empire’s slaughter of Armenians during World War I. He famously asked his professor why the killing of an individual (homicide) was a crime, but the killing of a million people was a matter of national sovereignty. The question haunted him. There were words like “massacre” or “barbarity,” but they felt insufficient. They described the bloody result, but failed to capture the cold, calculated intent—the coordinated plan to erase a culture, a language, a people from existence.

The urgency of this linguistic and legal void became terrifyingly personal for Lemkin with the rise of the Nazis. As a Jew in Poland, he foresaw the catastrophe. He escaped to the United States in 1941, but 49 members of his family, including his parents, were murdered in the Holocaust. His personal tragedy was a microcosm of a continental cataclysm. He knew that to prevent such atrocities from happening again, the world needed to be able to name, define, and prosecute the crime itself.

A Linguistic Architect at Work

Lemkin, a polyglot who spoke multiple languages, understood that the right word would need both precision and gravity. It couldn’t be a passing neologism; it needed to sound as ancient and fundamental as the crime it described. He embarked on a methodical linguistic quest, not as a poet, but as a legal architect designing a cornerstone for international law.

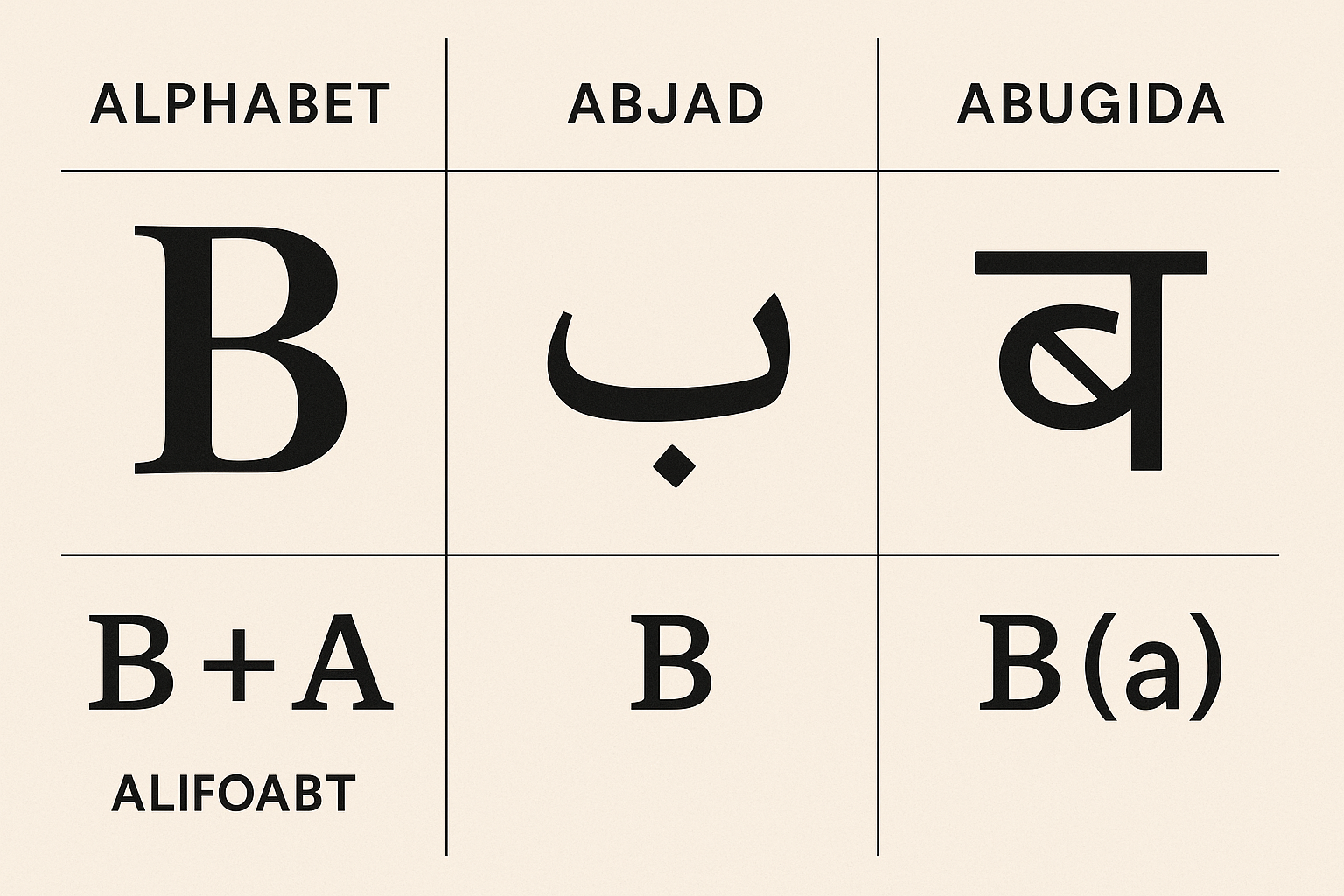

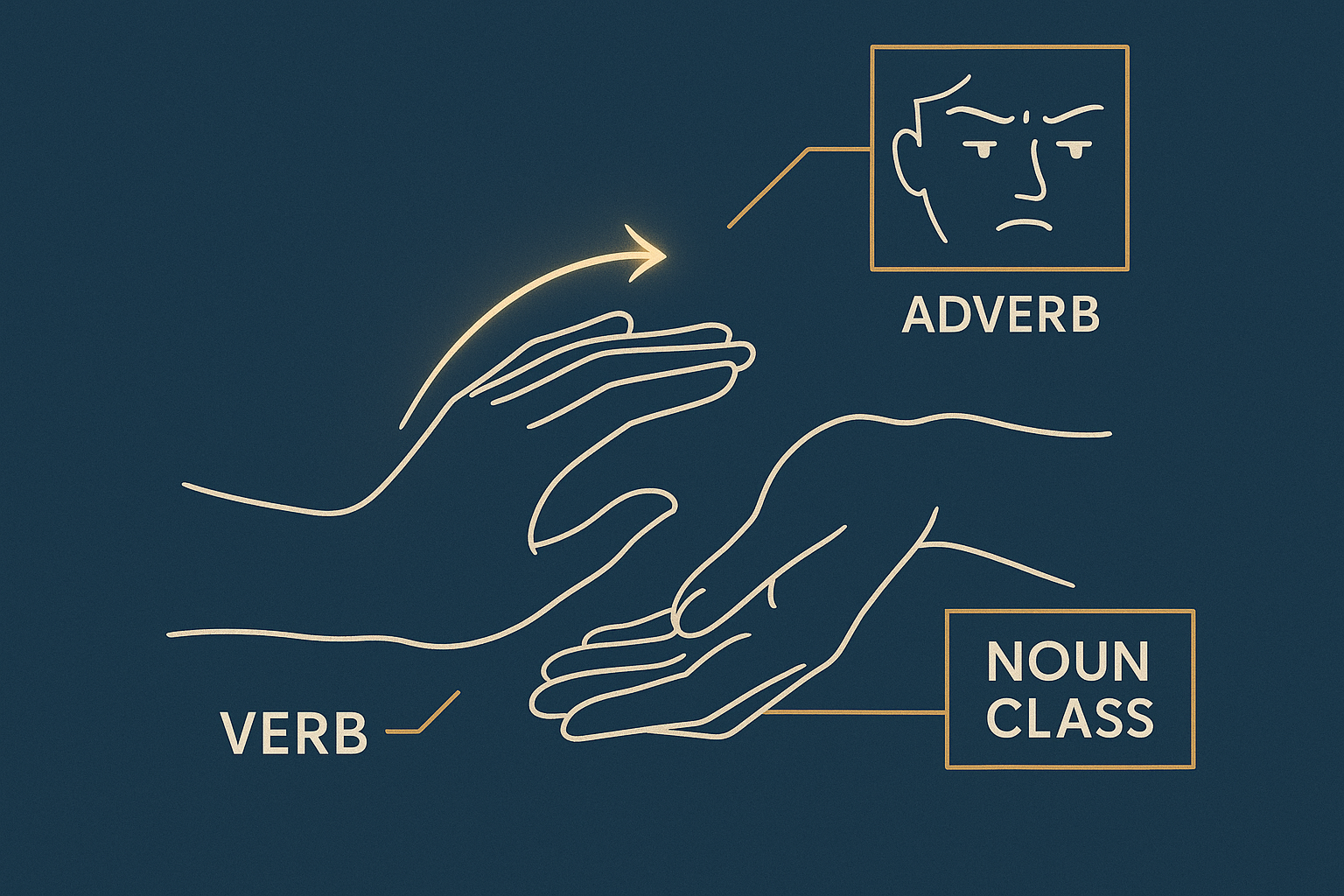

He turned to the classical languages that form the bedrock of Western legal and philosophical thought: Greek and Latin. His solution was a hybrid, a careful fusion of two powerful roots:

- Genos (γένος): From Ancient Greek, a word rich with meaning. It doesn’t just mean “race” in the modern, narrow sense. It encompasses the idea of a family, a tribe, a people, a nation, or any group bound by common descent or culture. This was crucial. Lemkin’s concept wasn’t limited to biological race; it included the destruction of national, ethnic, and religious groups. Genos captured that holistic sense of a collective identity.

- Cide: From the Latin verb caedere, meaning “to cut” or “to kill.” This suffix was already well-established in legal and common parlance. Words like homicide (killing a human), suicide (killing oneself), and patricide (killing one’s father) lent it a serious, clinical, and undeniably legal weight.

By marrying the Greek concept of the group with the Latin action of killing, Lemkin created genocide. It was perfect: concise, powerful, and rooted in a classical tradition that gave it immediate authority. The word didn’t just mean mass murder; it meant the *murder of a people*. It encapsulated the motive, the scope, and the unique horror of the act.

From a Book to International Law

Lemkin first officially introduced his creation to the world in his 1944 book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. He didn’t just define the word; he meticulously detailed the techniques of genocide beyond direct killing. He wrote about the systematic destruction of a group’s political and social institutions, culture, language, national feelings, religion, and economic existence. It was a holistic definition of destruction.

“Genocide is a new word… It is intended to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.” – Raphael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe

The word’s power was immediately apparent. It began to appear in press coverage of the war’s end. At the Nuremberg Trials, though “genocide” was not yet a formal charge under international law, the indictment against Nazi leaders accused them of “deliberate and systematic genocide.” The concept Lemkin had defined was now being used to hold the perpetrators of the Holocaust accountable.

But Lemkin’s work wasn’t finished. He became a tireless, one-man lobbying force at the newly formed United Nations. He haunted the hallways, buttonholing delegates, distributing literature, and passionately arguing for the crime of genocide to be enshrined in international law. His persistence paid off. On December 9, 1948, the U.N. General Assembly unanimously adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Lemkin’s word was now law.

The Enduring Power of a Name

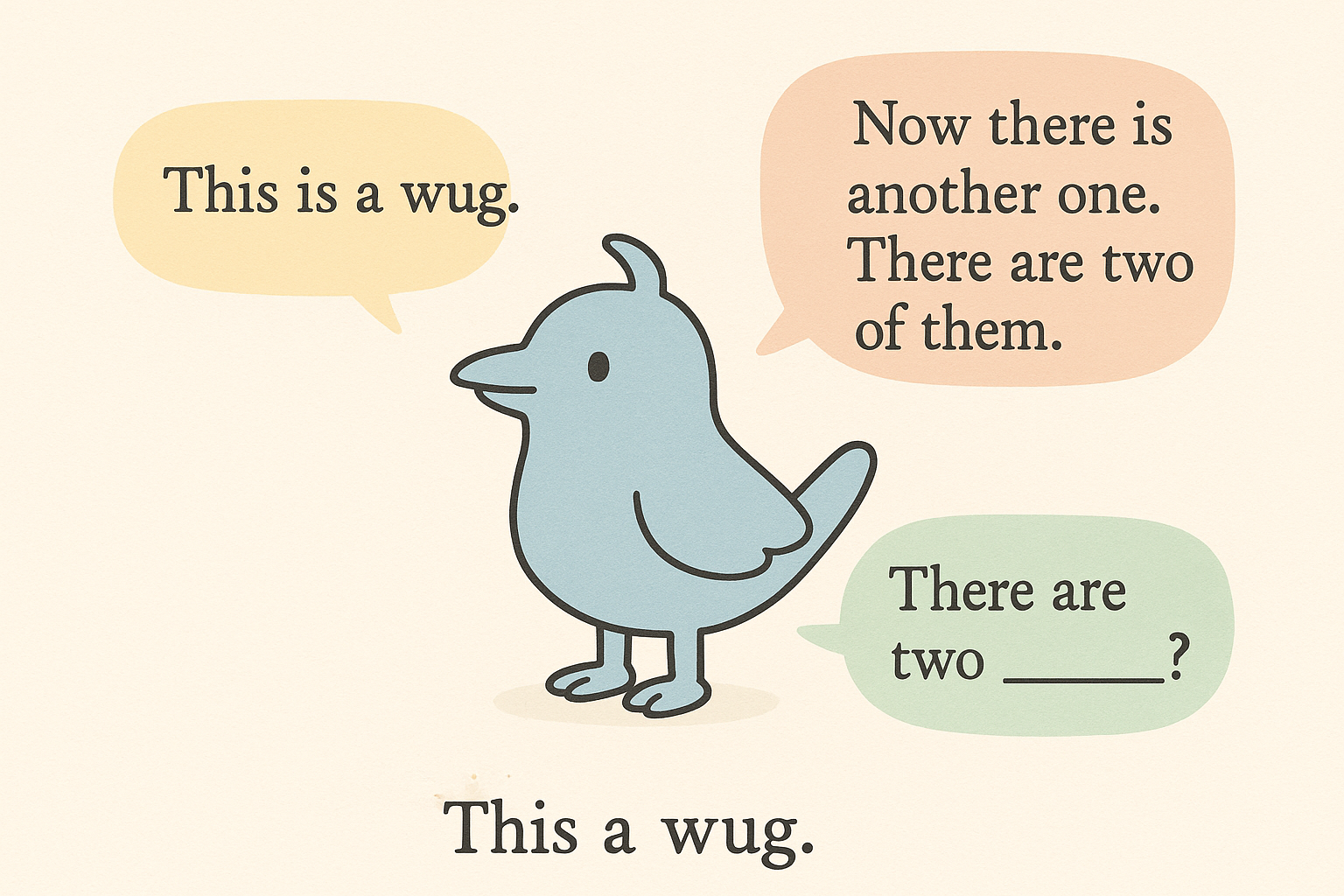

The story of Raphael Lemkin and the word “genocide” is a profound testament to the power of language. A word is not merely a label; it is a conceptual tool. By giving a name to the unspeakable, Lemkin gave humanity a way to see it, to understand it, and to build a legal framework to condemn it.

The term allows us to distinguish this specific crime from the general brutality of war. It forces us to confront the intent behind the horror. While the Genocide Convention has not, tragically, ended the practice, it has created a standard of accountability. It gives activists a banner, lawyers a charge, and historians a framework. Raphael Lemkin’s great linguistic achievement was a gift to humanity—a word forged in tragedy, built from ancient roots, that arms us with the clarity to say “never again,” and to know precisely what we mean.