The Mountain Fortress and the Old Man

Our story begins in the 11th century, not with a definition, but with a person and a place. The person was Hassan-i Sabbah, a charismatic and brilliant missionary for the Nizari Isma’ili sect of Shia Islam. The place was Alamut Castle, a formidable, near-impregnable fortress perched high in the Alborz mountains of northern Persia (modern-day Iran).

The Nizaris were a minority group facing persecution from the powerful Seljuk Empire. Outnumbered and outgunned, Hassan-i Sabbah developed a radical strategy for survival: asymmetrical warfare. Instead of fielding armies, he trained a select group of devoted followers, known as the Fida’i (“those who sacrifice themselves”), to carry out highly precise, targeted killings of key enemy military and political leaders. These missions were often suicidal, but they were devastatingly effective, sowing terror and chaos among Nizari enemies.

A Name Forged in Propaganda: The Ḥashīshiyyīn

The success of the Fida’i made them feared throughout the Muslim world. Their enemies needed a way to discredit them, to paint them not as devout believers with a political cause, but as soulless, drug-crazed fanatics. They found it in a single, powerful slur: Ḥashīshiyyīn (حشيشيين).

This Arabic term, meaning “hashish users,” was likely a pejorative label, a piece of medieval propaganda. There is little to no contemporary evidence from within the Nizari community that they actually used hashish or any other drug as part of their training or missions. The accusation was designed to strip them of their legitimacy. It suggested their fanatical loyalty wasn’t born from faith, but from intoxication and delusion.

This derogatory nickname, however, would be the seed from which the word ‘assassin’ would grow.

Marco Polo and the Legend of Paradise

For decades, the stories of the Ḥashīshiyyīn remained largely within the Middle East. It was the Crusaders, who encountered a Syrian branch of the Nizaris, who first brought tales of the fearsome sect back to Europe. But it was one man who cemented the legend into the Western imagination: Marco Polo.

In his famous 13th-century book, The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian merchant recounted a sensational and fantastical version of the story. He described the “Old Man of the Mountain” (a title for the Nizari leader) using a secret garden to control his young followers. According to Polo, the Old Man would drug them and have them carried to this garden, which was built to resemble the Islamic vision of paradise, complete with flowing wine, milk, honey, and beautiful maidens.

“He would have them carried into his garden, some four at a time, or six, or ten, and there he would have them awakened. When therefore they awoke, and found themselves in a place so charming, they deemed that it was Paradise in very truth. And the ladies and damsels dallied with them to their hearts’ content… So when the Old Man would have any Prince slain, he would say to such a youth: ‘Go thou and slay So and so; and when thou returnest my Angels shall bear thee into Paradise.'”

Polo’s account was a bestseller, read across Europe. It was thrilling, exotic, and terrifying. Though largely a fabrication built upon the old propaganda, his story was taken as fact. The legend of the hashish-eating, paradise-seeking killers was now inextricably linked to the Nizaris.

From Legend to Lexicon: A Word Crosses Borders

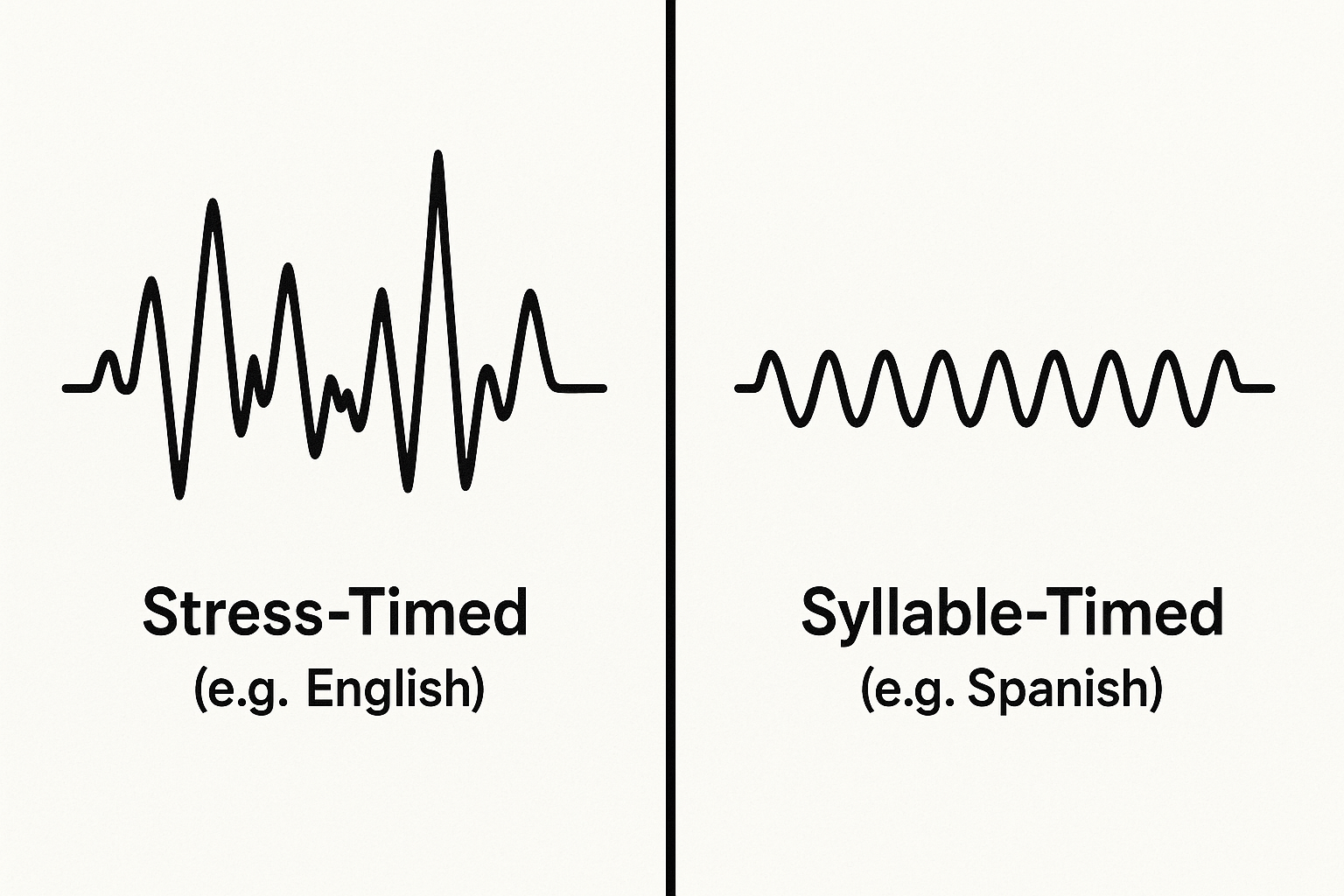

As tales of the Ḥashīshiyyīn spread, so did their name. European tongues, unfamiliar with Arabic, began to adapt the word. The journey looked something like this:

- Arabic: Ḥashīshiyyīn

- Medieval Latin: Assassini, Heyssisini

- Old French: Assassin

- Italian: Assassino

By the 14th century, the word had entered the English language, borrowed from French. At first, it was a proper noun, referring specifically to the followers of the Old Man of the Mountain. But its meaning soon began to broaden. The word’s power was too great to remain confined to a single historical group. Writers like Dante Alighieri, in his Inferno, used the Italian form assassino to refer to a treacherous murderer, showing the shift towards a more general meaning.

The Modern Assassin: A Legacy of Legend

The historical Nizari state at Alamut was eventually destroyed by the invading Mongols in 1256. But their legend, carried by the word ‘assassin,’ had achieved immortality. The word evolved from a specific slur into a common noun for any hired, skilled, or politically motivated killer.

Today, the word ‘assassin’ still carries the DNA of its dramatic past. It implies more than just ‘murderer.’ An assassin is often seen as a professional, a specialist shrouded in secrecy and mystique, whose actions have political or strategic consequences. This archetype is a direct descendant of the legends surrounding the Fida’i—an image amplified by centuries of storytelling, from Shakespeare to modern films and video games like Assassin’s Creed, which directly and creatively engages with this complex history.

The journey of ‘assassin’ is a perfect testament to how words are time capsules. Buried within its syllables is the story of a mountain fortress, a persecuted sect, a clever propaganda campaign, and a world-famous traveler’s tall tale. It reminds us that the language we use every day is a living museum, filled with artifacts that have stories to tell, if we only take a moment to listen.