The Astronomer and His ‘Channels’

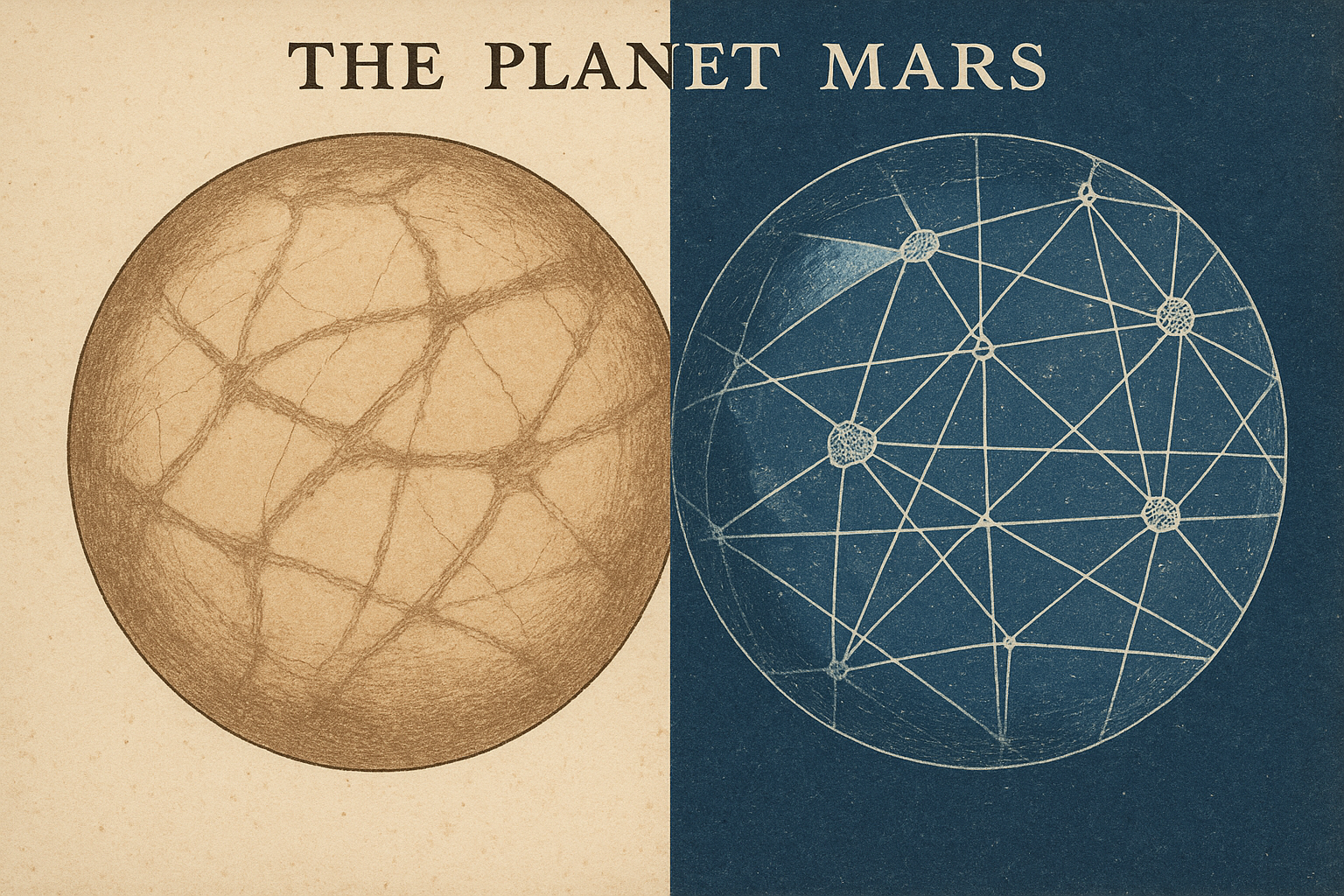

Our story starts in 1877. The planet Mars was making a particularly close approach to Earth, an event known as a perihelic opposition that gave astronomers an unusually clear view. In Milan, the director of the Brera Observatory, Giovanni Schiaparelli, turned his state-of-the-art telescope toward the ruddy disk. A meticulous and patient observer, Schiaparelli spent months painstakingly mapping the planet’s surface, noting its light and dark regions, which he named after mythological and historical places on Earth.

But he saw something else, too. Crisscrossing the lighter, reddish-ochre areas (the “continents”) was a dense, complex network of fine, dark, linear features. He documented dozens of them, giving them names from famous rivers on Earth, like the Ganges, the Nile, and the Indus. To describe these features in his native Italian, he used the word canali.

The Word That Launched a Thousand Spaceships

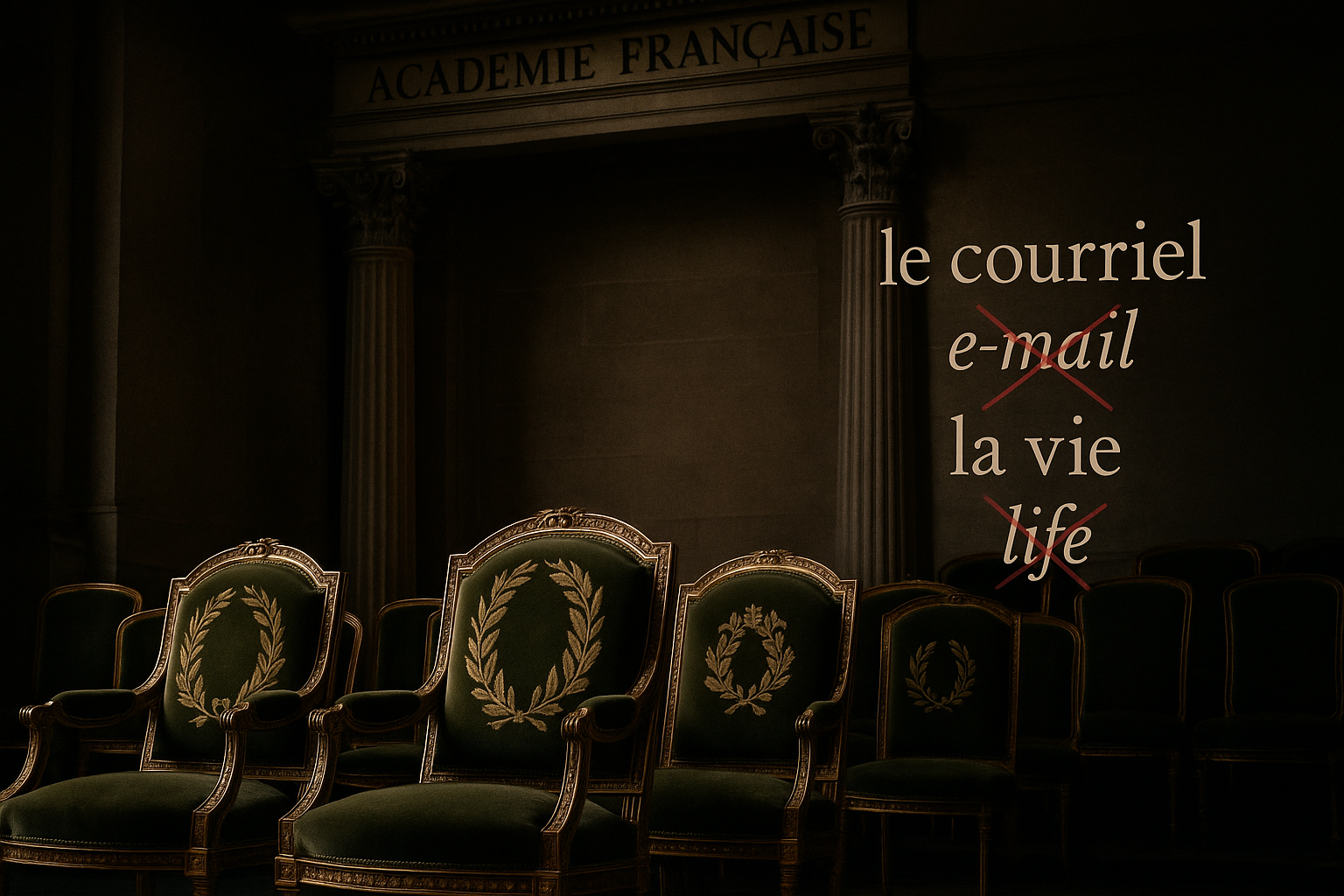

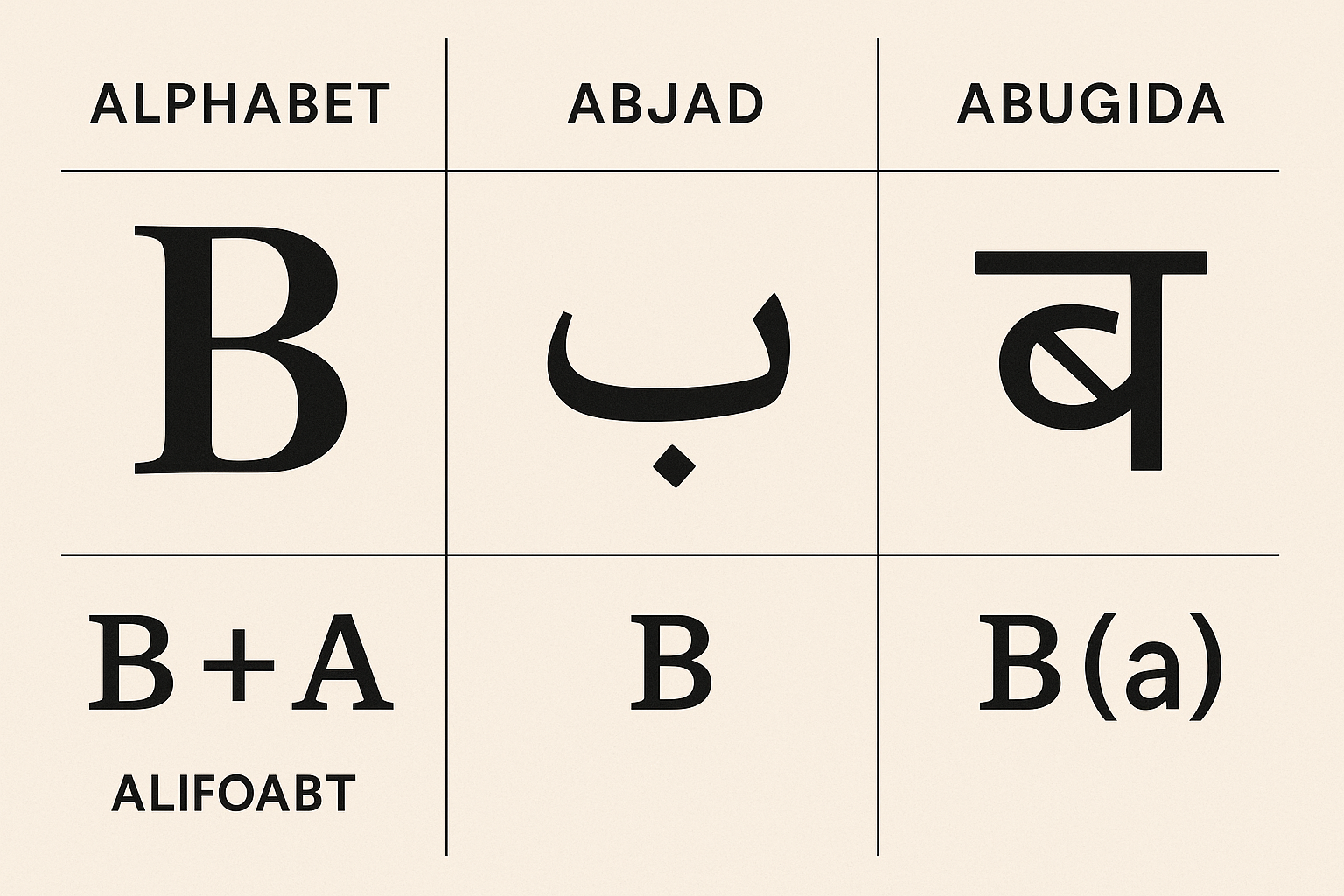

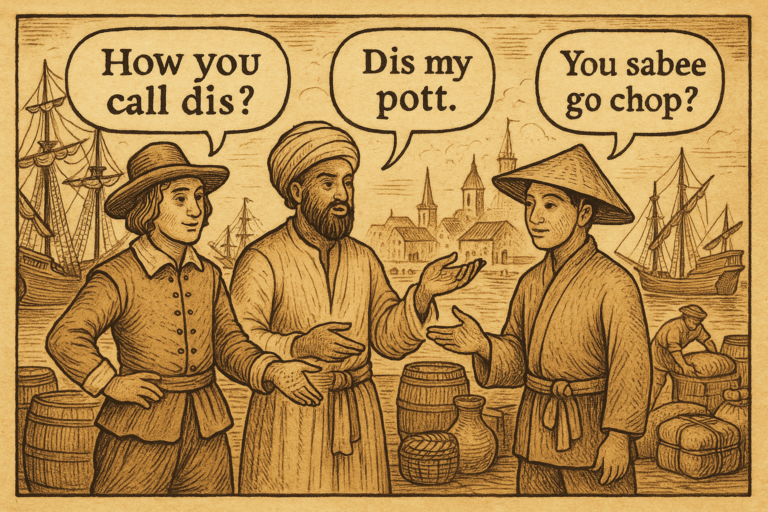

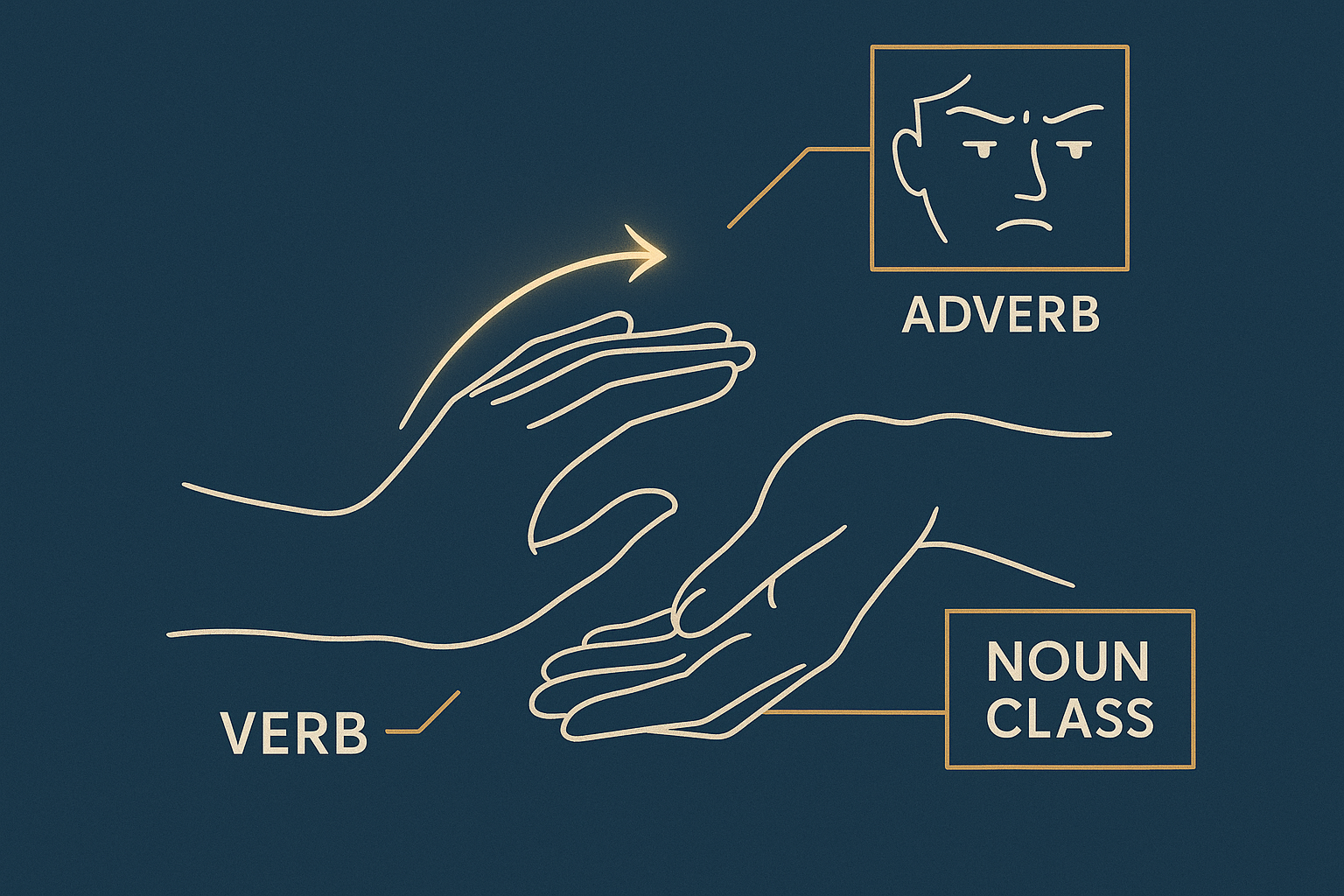

Here, at the intersection of observation and language, a world was born. In Italian, canali is the plural of canale. The word is wonderfully ambiguous. It can mean “canals,” as in artificial waterways like those in Venice. But it can just as easily, and more commonly, mean “channels,” “grooves,” or “gorges”—entirely natural formations. Think of the English Channel, a natural body of water; in Italian, it is “La Manica,” a *canale*.

Schiaparelli himself remained cautious and scientific. He never explicitly claimed the features were artificial. In fact, when communicating with international colleagues, he often chose his words carefully to avoid this very implication. He understood the linguistic trap. Yet, when his maps and descriptions were translated into English, the choice seemed obvious. Canali became “canals.”

The difference is monumental. A “channel” is a geographic feature. A “canal” implies engineers. It suggests intelligence, purpose, and design. With the stroke of a translator’s pen, Schiaparelli’s ambiguous observations were imbued with the staggering implication of extraterrestrial life.

An Idea Too Good to Disprove: Percival Lowell’s Martians

The idea of Martian “canals” might have remained a scientific curiosity if not for its most passionate and influential champion: Percival Lowell. A wealthy Bostonian, amateur mathematician, and charismatic astronomer, Lowell became utterly captivated by the notion of an engineered Mars.

He founded the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, in 1894, largely for the express purpose of studying these canals. With a powerful new telescope and the clear desert air, Lowell didn’t just confirm Schiaparelli’s findings—he took them to an entirely new level. Where Schiaparelli saw a few dozen lines, Lowell mapped hundreds. His drawings depicted a world covered in a breathtakingly complex, geometric web of perfectly straight lines, intersecting at points he called “oases.”

Lowell was more than an observer; he was a brilliant storyteller. In a series of popular and widely read books, including Mars (1895) and Mars as the Abode of Life (1908), he laid out his grand theory. Mars, he argued, was a dying world. Its ancient, intelligent, and desperate inhabitants had constructed a planet-wide irrigation system of colossal scale to channel water from the melting polar ice caps to their parched cities in the equatorial regions. It was a romantic, tragic, and scientifically plausible-sounding narrative that captured the public imagination like nothing before.

From Scientific Theory to Sci-Fi Trope

Lowell’s vision of a dying Martian civilization became the bedrock of 20th-century science fiction. The cultural impact was immediate and immense.

- H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898): While Wells never mentions canals explicitly, his concept of envious Martians on an “older, colder, dying” planet casting their eyes on Earth is a direct echo of Lowell’s popular theory.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom series (starting with A Princess of Mars, 1917): Burroughs took Lowell’s Mars and turned it into a pulp fantasy landscape of adventure, ancient cities, strange creatures, and, of course, canals that were part of a planetary atmosphere-generating system.

For more than half a century, this was Mars. Not just in fiction, but in the minds of the public and many scientists. The Red Planet was the abode of the “Martians,” the canal-builders, our enigmatic neighbors in the cosmos.

The Truth Revealed: A World Without Canals

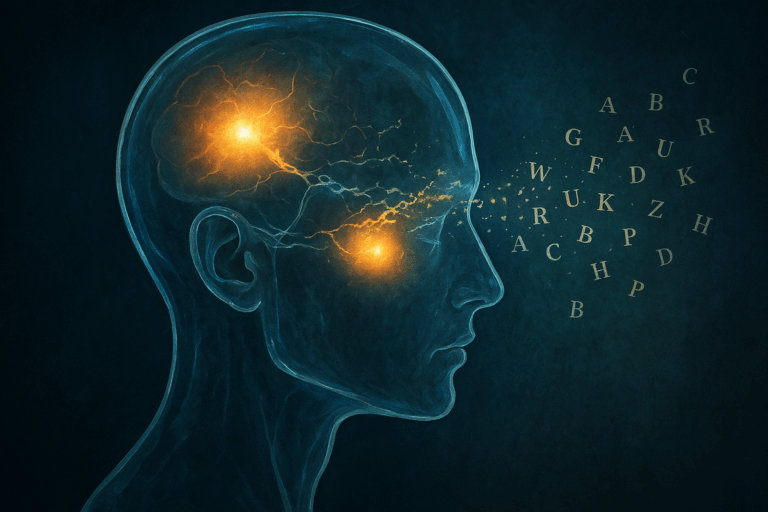

Even in Lowell’s time, there was deep skepticism. Many fellow astronomers, using equally powerful telescopes, simply couldn’t see the canals. They argued that what Lowell and Schiaparelli were observing was an optical illusion. The human brain is hardwired to find patterns, a phenomenon called apophenia. Staring for hours at a shimmering, low-contrast, blurry object at the limits of visibility could easily trick the eye and brain into connecting disparate dark spots—craters, rocks, and shadows—into straight lines.

The debate raged for decades, but the final, definitive answer came with the space age. In July 1965, NASA’s Mariner 4 spacecraft flew past Mars and sent back the first-ever close-up images of another planet. The 22 black-and-white pictures revealed a stark, beautiful, and disappointing reality.

Mars was a moon-like, crater-pocked, and utterly desolate world. There were no canals. No oases. No cities. Later missions like Mariner 9 and the Viking landers would map the entire planet in stunning detail, revealing giant volcanoes, vast canyons (like the Valles Marineris, a true natural *canale*), and polar ice caps, but nothing resembling Lowell’s intricate, artificial grid.

The Power of a Word

The story of the Martian canals is a perfect “false friend” in translation—a word that looks and sounds the same but carries vastly different connotations. Schiaparelli’s *canali* were a cautious description; Lowell’s “canals” were a declaration of intelligent life.

This single-word saga is more than a historical curiosity. It’s a profound lesson in how language doesn’t just describe our world but actively shapes our perception of it. The translation from “channels” to “canals” was not just a linguistic error; it was a conceptual leap that injected intention, narrative, and an entire civilization into a blurry astronomical observation. It reminds us that translation is never a simple act of substitution but a complex art of cultural and conceptual interpretation—an art so powerful it can, for a time, give us a whole new world.