Clicks, Pops, and Whistles: A Journey into the World’s Rarest Speech Sounds

Take a moment and listen to the sounds of English. You have the soft hum of an ‘m’, the sharp hiss of an ‘s’, the gentle flow of vowels. For most of us, the sounds of our native tongue form the entire universe of what we consider “speech.” But what if I told you this familiar palette is just one small corner of a vast, vibrant gallery of human sound? What if there were languages built on percussive clicks, forceful pops, and even melodic whistles that carry for miles?

Welcome to the world of phonetic rarities. This is a journey beyond the comfortable consonants and vowels of languages like English or Spanish, into the wild and wonderful frontiers of human communication. We’ll explore how different cultures have harnessed the incredible potential of our vocal anatomy to produce sounds you may have never thought possible.

The Rhythmic Clicks of Southern Africa

Perhaps the most famous of all “exotic” sounds are the click consonants. If you’ve ever made a “tsk-tsk” sound to express disapproval or a clucking noise to urge on a horse, you’ve produced a click. Now, imagine weaving those sounds into the very fabric of every other word. That’s the reality for speakers of the Khoisan languages of Southern Africa, as well as several neighboring Bantu languages like Xhosa and Zulu.

What makes clicks unique is their airstream mechanism. Most speech sounds are egressive, meaning we create them by pushing air out of our lungs. Clicks, however, are ingressive. They are made by creating two closures in the mouth, rarefying the air in the pocket between them, and then releasing the forward closure, which causes air to rush into the mouth, creating a sharp “pop” or “click.”

The Khoisan languages, particularly the Taa language (also known as !Xóõ), possess the most complex sound systems on Earth, with some dialects featuring over 100 distinct sounds, a huge portion of which are clicks. There are several primary types of clicks:

- Dental Click (IPA symbol: ǀ): The “tsk-tsk” sound, made with the tongue against the back of the front teeth. You hear this in the language name Xhosa (the ‘Xh’ represents a type of click).

- Alveolar Click (IPA symbol: ǃ): A much sharper, louder pop made by pulling the tip of the tongue down from the ridge behind the teeth. Often likened to the sound of a cork popping from a bottle.

- Lateral Click (IPA symbol: ǁ): The sound made on the side of the mouth, often used to call horses. It’s a key feature in the name of the Zulu king Shaka kaSenzangakhona.

These clicks aren’t just novelties; they are foundational consonants, as integral to their languages as ‘p’ or ‘t’ are to English. Their existence is a powerful testament to the ingenuity of human speech and a window into the deep linguistic history of the African continent.

The Forceful Pops of Ejectives

Now let’s travel north, to the mountainous Caucasus region, home to languages like Georgian, Chechen, and Avar. Here, another fascinating class of sounds reigns: ejectives.

Like most English consonants, ejectives are egressive (air pushes out). However, they use a different power source. Instead of air coming directly from the lungs, the speaker closes their glottis (the space between the vocal cords), trapping the air in the throat. They then raise their larynx, pressurizing this trapped air, and release it with a sharp, popping quality when making a consonant like ‘p’, ‘t’, or ‘k’.

The result is a sound that is noticeably more forceful and staccato than its English counterpart. To get a rough idea, try to say the letter ‘k’ while holding your breath. That sharp release is approaching the quality of an ejective. The difference is subtle to an untrained ear but phonemically crucial for a native speaker.

For example, in Georgian, the word for “frog” is ბაყაყი (baq’aq’i), where the “q'” represents an ejective ‘k’-like sound made further back in the throat. Distinguishing it from a regular ‘k’ is essential for meaning. While they are a hallmark of the Caucasus, ejectives are also found across the globe in Native American languages like Quechua and Mayan, and in many languages of Africa and the Americas, showcasing a case of convergent evolution in phonetics.

Whispering on the Wind: The World of Whistled Speech

Our final stop is not about a single type of sound, but an entire mode of communication. In rugged, mountainous, or densely forested parts of the world, shouting is often impractical. The sound gets lost in the terrain. The solution? Whistling.

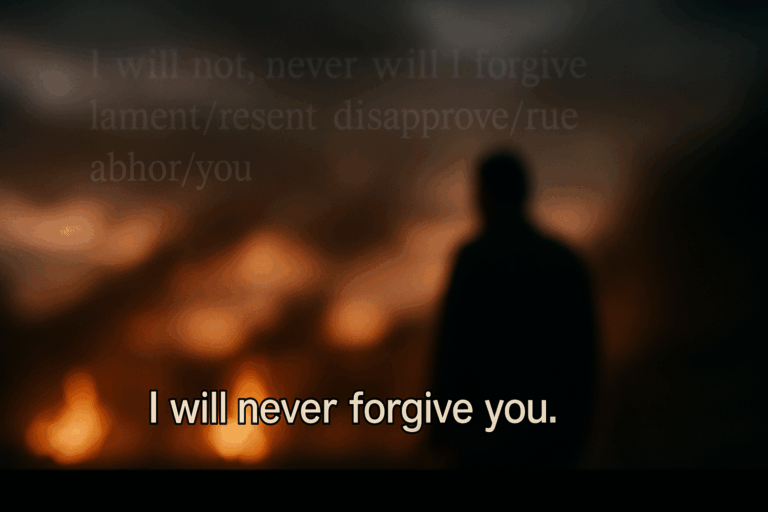

Whistled languages are not independent languages like Morse code. They are whistled versions of a local spoken language. Speakers transform the pitch contours (melody) and rhythm of their spoken sentences into whistles of varying frequencies. A rising intonation in a spoken question becomes a rising whistle; a stressed syllable becomes a higher-pitched or louder whistle.

This allows for complex messages to be transmitted over distances of several kilometers. It’s the ultimate form of long-distance, low-tech communication.

Some of the most famous examples include:

- Silbo Gomero: Used on the island of La Gomera in the Canary Islands, this is a whistled form of Spanish. After facing decline, it’s now a protected cultural treasure and is even taught in schools.

- Kuşköy’s “Bird Language”: In a village in northern Turkey, locals use a whistled form of Turkish to communicate across deep valleys. Phrases like “Come for tea” or “Help is needed” fly through the air as complex melodies.

- Mazatec and Chinantec languages: In Oaxaca, Mexico, several indigenous communities use highly complex whistled speech, capable of conveying any sentence that can be spoken.

Whistled languages demonstrate that language is not just about consonants and vowels, but also about melody, rhythm, and tone—and that humans can adapt these core features to any medium available, even the wind itself.

More Than Just Noise: Why This Diversity Matters

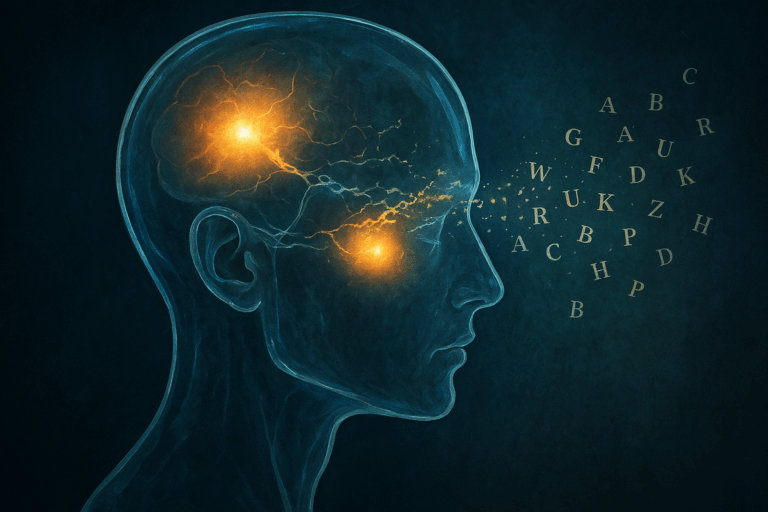

Exploring these rare sounds is more than just a linguistic curiosity. It’s a profound reminder of the cognitive and physiological flexibility of our species. The human vocal tract is an incredibly versatile instrument, and cultures across the globe have composed unique symphonies with it.

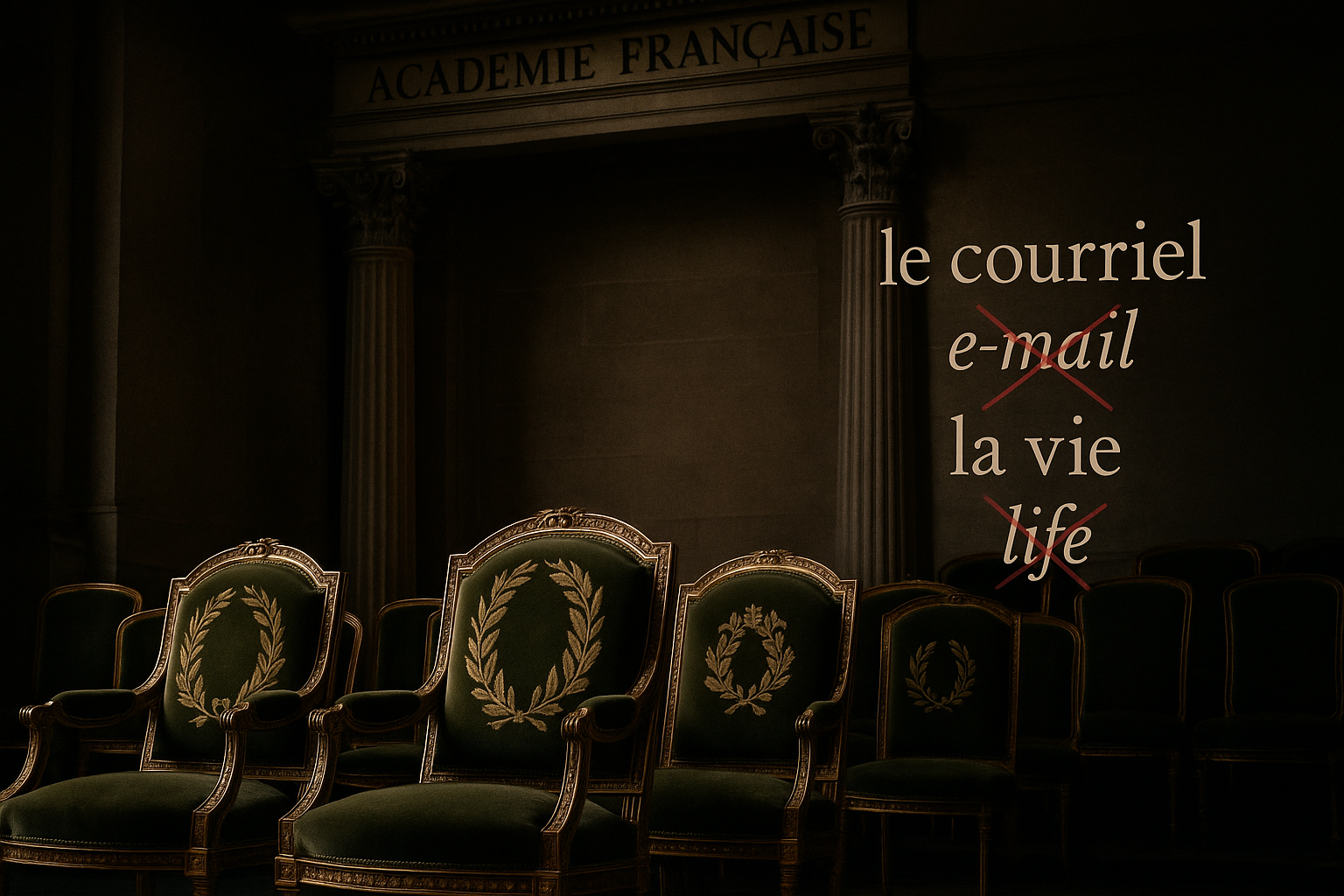

This phonetic diversity is a key part of our shared human heritage. Sounds tell stories of migration, contact, and isolation. The borrowing of clicks into Bantu languages tells a story of interaction with Khoisan peoples. The prevalence of ejectives in certain regions points to ancient linguistic areas. But just like the world’s biodiversity, its linguistic diversity is under threat. With every language that falls silent, we lose not just words and grammars, but sometimes, entire families of sounds that exist nowhere else.

So the next time you speak, take a moment to appreciate the sounds you make. And remember that out there, beyond the familiar, there are clicks, pops, and whistles—a beautiful, complex, and endangered symphony of human expression.