One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine… ten. We bundle, we package, we think in tens. A decade is ten years. A dollar is ten dimes. The metric system, the very model of rational measurement, is built entirely on the power of ten. It feels so natural, so intrinsically right, that we rarely stop to ask a fundamental question: why ten?

The most common answer is elegantly simple: look down at your hands. We are creatures with ten fingers, our first and most accessible abacus. This biological quirk has profoundly shaped human cognition and civilization. But what if we had evolved differently? Or what if we simply decided to use a different set of tools for counting? As it turns out, we don’t need to speculate. Many cultures throughout history did exactly that, looking beyond their fingers and building sophisticated mathematical worlds on a different foundation: the number twenty.

Beyond the Decimal: Welcome to the Vigesimal World

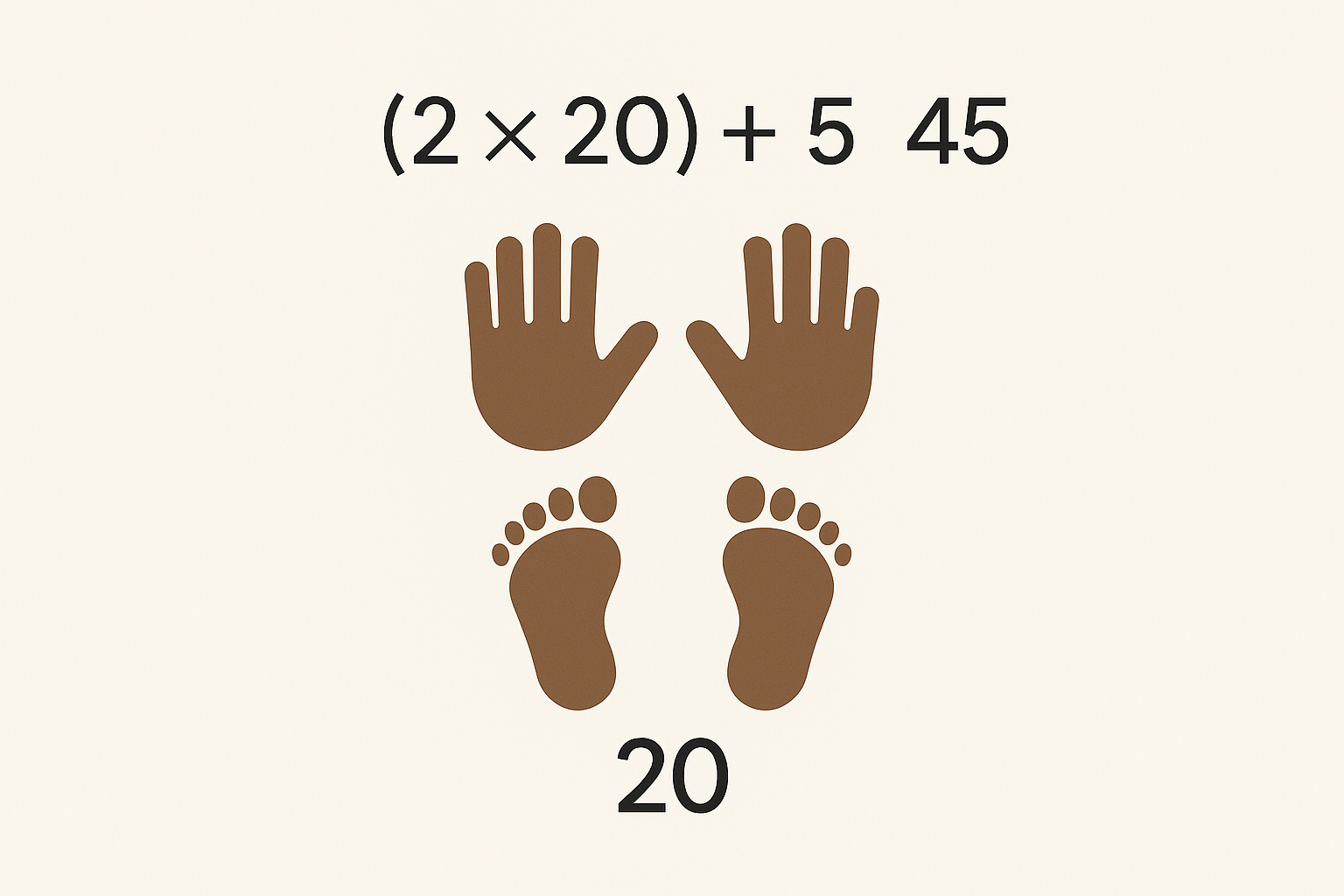

This is the world of vigesimal, or base-20, counting. The logic is just as intuitive as base-10, but it uses a wider frame of reference. If ten comes from our fingers, twenty comes from our fingers and our toes. A full set. In many of these systems, the word for “twenty” is often synonymous with “man” or “person,” representing one complete count of all available digits.

In a base-10 (decimal) system, we group by tens. The number 37 is three groups of ten, plus seven units (3 x 10 + 7). In a base-20 (vigesimal) system, the fundamental grouping is twenty. The same number, 37, becomes one group of twenty, plus seventeen units (1 x 20 + 17). The number 40 isn’t “forty;” it’s “two twenties.” 85 isn’t “eighty-five;” it’s “four twenties and five.”

This isn’t just an abstract mathematical exercise. Vigesimal systems arose independently across the globe, embedding themselves so deeply into language that they reveal a completely different way of conceptualizing quantity.

A Journey Through Vigesimal Languages

While remnants of base-20 can be found hiding in familiar languages (think of the French quatre-vingts for 80, literally “four-twenties”), some cultures built their entire numerical worldview around it. Let’s explore a few of the most remarkable examples.

The Maya: Astronomers and Mathematicians

Perhaps the most famous and sophisticated vigesimal system belongs to the ancient Maya of Mesoamerica. Their mathematics were breathtakingly advanced, allowing them to make precise astronomical observations and develop famously complex calendars. Their written number system was elegant and efficient, using only three symbols:

- A dot for one

- A horizontal bar for five

- A shell glyph for zero

The inclusion of zero, developed independently of its invention in India, was a revolutionary concept that allowed for a true positional number system. Numbers were written vertically, with the lowest values at the bottom. The number 19 would be four dots above three bars (4 + 5 + 5 + 5). The number 20 would be a single dot in the “twenties” position, with a zero shell in the “ones” position below it. It was a system as logical and powerful as our own.

Interestingly, for their “Long Count” calendar, the Maya used a modified vigesimal system. While most positions increased by a factor of 20, the third position increased by a factor of 18, making the cycle 360 days (18 x 20), a close approximation of a solar year. This demonstrates a culture adapting its mathematical tools for specific, practical purposes.

Basque: A European Outlier

Tucked away in the Pyrenees Mountains between Spain and France, the Basque language (Euskara) is a language isolate, unrelated to any other in Europe. Its number system is a living museum of vigesimal counting.

While Basque has adopted decimal words for larger numbers under the influence of Spanish and French, its core structure is vigesimal.

- 20 is hogei

- 30 is hogeita hamar (“twenty and ten”)

- 40 is berrogei (“two-twenties”)

- 60 is hirurogei (“three-twenties”)

- 80 is laurogei (“four-twenties”)

To say “75” in Basque, you construct it as hirurogeita hamabost, which breaks down to “three-twenties and fifteen” (3 x 20 + 15). The number isn’t conceived as seven tens and a five, but as three full “persons” worth of digits and fifteen more.

Ainu and the Art of Subtraction

The Ainu, an indigenous people of northern Japan and surrounding islands, also employed a base-20 system, but with a fascinating twist. Their system often used subtraction to name numbers approaching the next group of twenty. For example, the number 30 is wanpe etu hotnep, which literally translates to “ten from two twenties” (2 x 20 – 10). This subtractive principle, also seen in Latin (e.g., “duodeviginti” for 18, or “two from twenty”), shows another layer of cognitive flexibility in how base systems can be implemented.

Does Counting in Twenties Change How You Think?

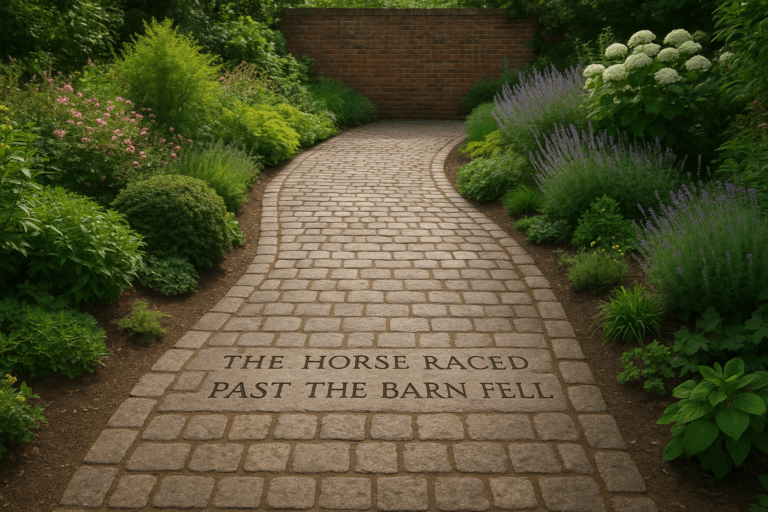

This leads to a fascinating question at the heart of linguistics: does the language you speak change the way you think? The idea of linguistic relativity suggests that it does, at least to some extent.

Learning mathematics in a vigesimal language doesn’t make you better or worse at calculus, but it does fundamentally alter how you group and perceive numbers in everyday life. For a native English speaker, 100 is the ultimate “round number.” For a speaker of Welsh (another language with vigesimal traces), 40 (deugain) and 60 (trigain) have a certain “roundness” that 50 lacks. For a French speaker, 80 (quatre-vingts) feels like a more complete, composite number than 70 or 90.

The number 77 in English is “seventy-seven,” a clear structure of 7 groups of 10 plus 7. In Basque, as we saw, it’s conceptualized as 3 groups of 20 plus 17. The mental “chunking” of the number is entirely different. This influences mental arithmetic, estimation, and the very rhythm of counting.

Our World is More Than Ten

The story of base-20 is a powerful reminder that our own way of seeing the world—even something as objective as mathematics—is filtered through the lens of our culture and language. The decimal system, born of our ten fingers, is practical and effective, but it is not the only way. The vigesimal systems of the Maya, Basque, Ainu, and dozens of other cultures show us a world built on a different scale.

They invite us to look down not just at our hands, but at our feet, and to appreciate that the landscape of human thought is far richer and more varied than we might imagine. Our comfortable world of tens is just one neighborhood in a vast metropolis of human ingenuity.