Imagine the Hebrew Bible not as a single book, but as an ancient library. On its shelves are epic poems, detailed legal codes, royal histories, and prophetic proclamations. For centuries, readers have studied its theological and historical content. But what if the very words themselves—the grammar, the vocabulary, the sentence structure—were a key to unlocking its hidden timeline? This is the work of linguistic archaeology, a fascinating field that treats the Hebrew language as a series of geological strata, each layer revealing the era in which it was formed.

The Bible was not written in one sitting. Scholars agree it’s a collection of texts composed, edited, and compiled over a millennium, from roughly 1200 BCE to 200 BCE. Just as an English speaker today can easily distinguish the language of Beowulf from that of Shakespeare, and Shakespeare from that of a modern blog post, so too can philologists identify distinct periods of ancient Hebrew. By tracing these linguistic shifts, we can watch the language evolve and, in doing so, create a timeline embedded within the text itself.

The Oldest Layer: Archaic Biblical Hebrew

At the very bottom of our linguistic dig site, we find Archaic Biblical Hebrew (ABH). This is the language of the Bible’s most ancient poems, texts believed to predate the Israelite monarchy. They feel rugged, powerful, and linguistically distinct from the prose that surrounds them. The two most famous examples are the “Song of the Sea” in Exodus 15 and the “Song of Deborah” in Judges 5.

What makes this Hebrew so old? Several key features stand out:

- Archaic Pronouns: In later Hebrew, the word for “who” or “which” is asher (אֲשֶׁר). In these ancient poems, we find the much shorter forms zeh (זֶה) or zu (זוּ) used as relative pronouns.

- The -mo Suffix: Possessive and object suffixes in Hebrew usually end with -hem or -am (“their” or “them”). ABH often uses a distinctive -mo ending, as in teromememo (“you will exalt them”). This suffix is almost entirely absent from later texts.

- Unique Vocabulary: These poems contain words that fell out of use, preserved like linguistic fossils. They are remnants of an older, perhaps Canaanite, poetic tradition.

These features connect Archaic Biblical Hebrew more closely to other ancient Northwest Semitic languages, like Ugaritic, than to the Hebrew of later biblical books. The content of these poems—celebrating victories in battle with chariots and warriors—paints a picture of a tribal, pre-state society, a world far removed from the later concerns of kings and priests.

The Standard Prose: Classical Biblical Hebrew

Moving up a layer, we arrive at the most common form of Hebrew in the Bible: Standard or Classical Biblical Hebrew (CBH). This is the language of the great narrative works, including much of the Torah (Genesis, Numbers), the Former Prophets (Joshua, Samuel, Kings), and the early prophets. This was the literary standard during the height of the monarchies of Israel and Judah (roughly 1000-586 BCE).

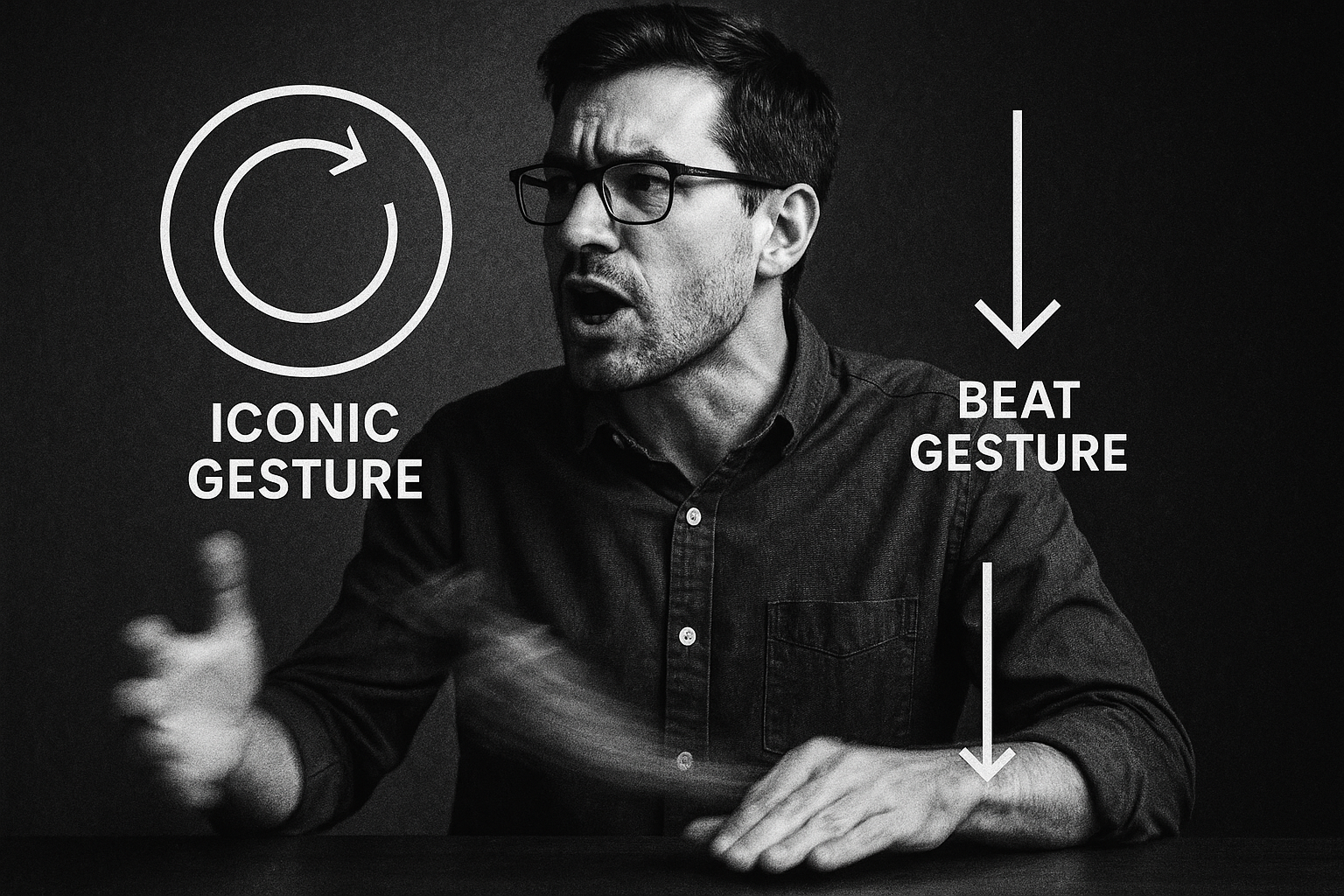

CBH is characterized by a fluid and powerful narrative tool known as the waw-consecutive. This grammatical feature allows writers to string together a sequence of past actions by placing the letter vav (ו, meaning “and”) before a verb. It creates a flowing, propulsive narrative style: “And he went… and he saw… and he said…” This structure dominates the storytelling of books like 1 Samuel and 2 Kings, giving them their characteristic pace and coherence.

This was the golden age of biblical prose, the language of a confident, centralized state with a sophisticated scribal culture. The grammar is relatively consistent, the vocabulary rich and expressive. It is the bedrock against which we measure both older and later forms of the language.

After the Exile: Late Biblical Hebrew

In 586 BCE, the Babylonian Empire destroyed Jerusalem and its Temple, forcing the Judean elite into exile. When the exiles and their descendants began to return under Persian rule decades later, their world had changed—and so had their language. This final major stratum is known as Late Biblical Hebrew (LBH).

The books written during this period (roughly 538-200 BCE), such as Ezra, Nehemiah, Chronicles, and Esther, display clear linguistic shifts:

- Aramaic Influence: Aramaic was the lingua franca of the Persian Empire. It was the language of administration and diplomacy. LBH is filled with Aramaic loanwords, particularly for legal and governmental terms like medinah (מְדִינָה, “province”) and pitgam (פִּתְגָם, “decree”). Even entire sections of Ezra and Daniel are written in Aramaic.

- Decline of the Waw-Consecutive: The classic narrative verb form of CBH becomes less common, often replaced by other constructions that more closely resemble later Mishnaic Hebrew.

- New Vocabulary and Grammar: The relative pronoun she- (שֶׁ), which is the standard in Modern Hebrew, begins to appear alongside the classical asher. Many older words are replaced with newer ones, reflecting a natural linguistic evolution.

A Tale of Two Texts: From Chariots to Covenants

Let’s place two passages side-by-side to see the difference. First, a taste of the archaic poetry from the Song of the Sea (Exodus 15:2), celebrating the escape from Egypt:

זֶה אֵלִי וְאַנְוֵהוּ אֱלֹהֵי אָבִי וַאֲרֹמְמֶנְהוּ

Zeh Eli v’anvehu, Elohei avi va’aromemenhu.

“This is my God, and I will praise Him; my father’s God, and I will exalt Him.”

The language is terse, poetic, and uses the standalone zeh (“this”) in a way that feels ancient and monumental. The focus is on a mighty warrior God who has just triumphed in battle.

Now, compare that to the administrative language of Ezra 1:2-3, a decree from the Persian king Cyrus allowing the Jews to return to Judah:

כֹּל מַמְלְכוֹת הָאָרֶץ נָתַן לִי יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵי הַשָּׁמָיִם וְהוּא פָקַד עָלַי לִבְנוֹת לוֹ בַיִת בִּירוּשָׁלִַם אֲשֶׁר בִּיהוּדָה.

Kol mamlechot ha’aretz natan li Adonai Elohei hashamayim, v’hu pakad alai livnot lo vayit bi’Yerushalayim asher bi’Yehudah.

“All the kingdoms of the earth the LORD, the God of heaven, has given me. And He has charged me to build him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah.”

The difference is stark. The language here is prose, not poetry. It has a legal, official tone. It uses the classical relative pronoun asher. The concerns are not with chariots and seas, but with royal decrees, provincial geography (“which is in Judah”), and the administrative task of rebuilding—a covenantal project sanctioned by an imperial power.

By analyzing these linguistic clues, we move from the world of Bronze Age epic poetry to the bureaucratic reality of the Persian Empire. The language itself tells the story of Israel’s journey from a confederation of tribes to a monarchy, and finally to a post-exilic community redefining itself through law and memory.

The Hebrew Bible is far more than a source of religious doctrine; it is a living document of language. Its words, phrases, and grammatical quirks are the echoes of history, allowing us to hear the distinct voices of poets, scribes, and administrators across the centuries. It’s an archaeological dig where the spade is philology, and the artifacts are the very words of the text.