You type “best place to see northern lights without a car” into the search bar. A moment later, you’re presented with a list of articles about Tromsø, Norway, complete with links to airport bus schedules and walkable aurora-viewing spots. The search engine didn’t just match your keywords; it understood your intent. It grasped the concepts of travel, accessibility, and a specific natural phenomenon. It read your mind.

This isn’t magic; it’s linguistics. Every time you use a search engine, you’re interacting with one of the most sophisticated and widely used linguistic machines ever built. Let’s pull back the curtain and explore how these digital linguists are taught to understand the beautiful, messy, and often ambiguous nature of human language.

Beyond Simple Keywords

In the early days of the internet, search engines were little more than digital indexers. They worked by matching the exact keywords in your query to the words on a webpage. A search for “baking recipes for cakes” would look for pages containing precisely those words. It wouldn’t necessarily understand that a page titled “How to Bake a Great Cake” was a perfect match.

The core challenge for modern search is that humans don’t communicate in keywords. We use synonyms, we make typos, we ask questions, and we imply context. To deliver relevant results, a search engine must move beyond matching text and start understanding meaning. This journey begins at the level of the individual word.

Deconstructing Words: Stemming vs. Lemmatization

To understand a query, a search engine first needs to break it down into its component parts and understand the relationship between different forms of the same word. Is “running” the same as “ran”? For a human, obviously. For a computer, it requires a process.

Stemming: The “Chop It Off” Method

Stemming is a crude but fast way to simplify words. It works by chopping off prefixes and suffixes to get to a common base form, or “stem.”

- running, runs, and ran might all be reduced to the stem run.

- fishes, fishing, and fished would become fish.

This is useful for grouping related terms, but it’s a blunt instrument. An aggressive stemmer might incorrectly reduce “university” and “universal” to the same stem, “univers,” confusing two distinct concepts.

Lemmatization: The “Smart Dictionary” Method

Lemmatization is a far more sophisticated and linguistically aware process. Instead of just chopping off letters, it tries to find the root word, or “lemma,” by considering its part of speech and using a dictionary-like understanding of the language.

- It knows that “ran” is the past tense of the verb to run.

- It understands that “better” is the comparative form of good, a connection stemming would completely miss.

- It can distinguish between “meeting” as a noun (from meeting) and “meeting” as a verb (from to meet).

Lemmatization is computationally more expensive, but it provides a much more accurate foundation for understanding the real meaning of the words in your query.

Understanding the Big Picture: Syntax and Semantics

Once the words are understood, the search engine must figure out how they fit together. This is where syntax and semantics come in.

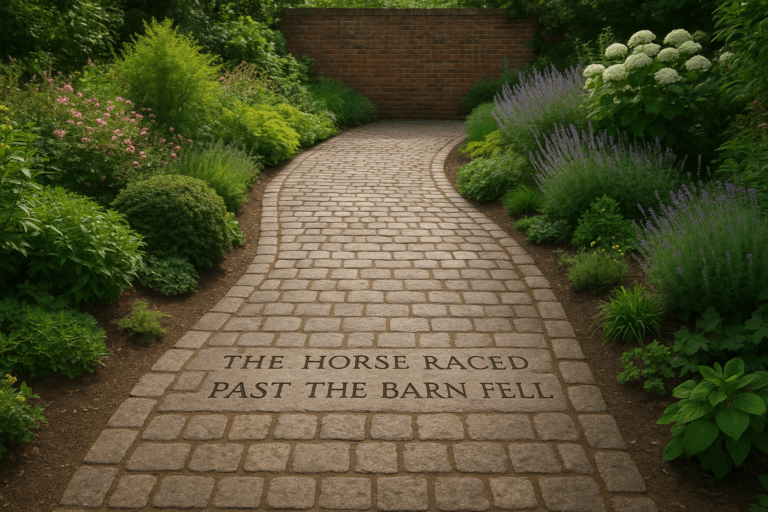

Syntax: The Grammar Police

Syntax is the set of rules that governs the structure of sentences. Word order matters immensely in human language, and search engines know this. They analyze the grammatical structure of your query to understand the relationships between the words.

Consider the classic linguistic example:

“Dog bites man” vs. “Man bites dog”

The words are identical, but the syntax—the subject-verb-object structure—completely changes the meaning. By parsing your query’s syntax, the engine can distinguish between a search for “flights from London to Paris” and “flights from Paris to London.”

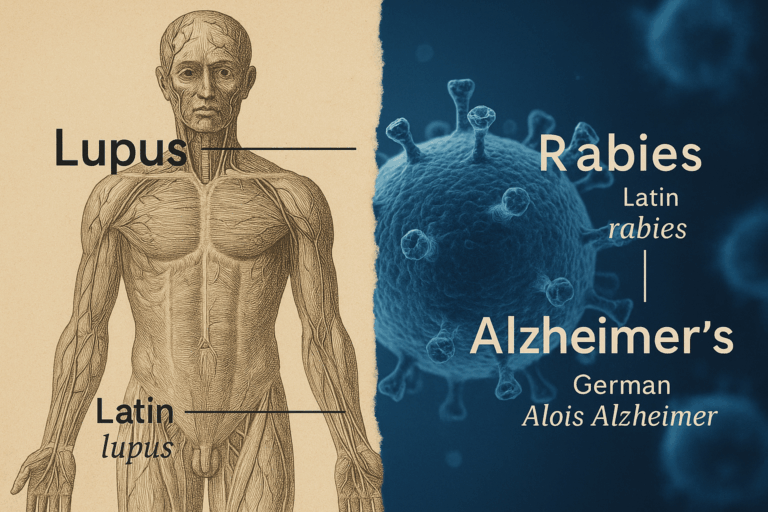

Semantics: The Meaning Detective

If syntax is about structure, semantics is about meaning and intent. This is where search engines truly seem to “read your mind.” They achieve this by building massive networks of information about how concepts, people, places, and things relate to one another. Google calls this its “Knowledge Graph.”

When you search for “how old is the actor from Mission Impossible,” the engine performs a semantic analysis:

- It recognizes “Mission Impossible” as a film franchise (an entity).

- It knows this entity has a relationship with another entity, “Tom Cruise” (the actor).

- It understands “how old” is a question about a specific attribute (age).

- It then retrieves that attribute for that entity and gives you a direct answer: 62 years old.

Semantic analysis also helps resolve ambiguity. If you search for “Java,” are you looking for the Indonesian island, the coffee, or the programming language? The engine uses other words in your query (“Java tutorial”) or your past search history to infer your intent and provide the most relevant results.

The Human Touch: Forgiveness and Intuition

Finally, a good search engine has to account for human error and our tendency to speak in shorthand.

Spelling Correction

The “Did you mean…?” feature is a linguistic marvel. It’s not just a simple spell-checker. It’s built on statistical models of language. The engine sees that millions of people who search for “lingustics” almost always click on results for “linguistics.” It learns this connection and offers the correction, saving us from our own typos.

Query Expansion

This is the engine’s ability to read between the lines. When you search for “used car,” you’re probably also interested in “pre-owned vehicle” or “secondhand auto.” The engine automatically expands your query to include these synonyms and related concepts, casting a wider net to find the best possible information, even if it doesn’t contain your exact phrasing.

The next time a search engine uncannily intuits your needs from a short, misspelled, or vague query, you’ll know it’s not telepathy. It’s a testament to decades of progress in computational linguistics. You’re witnessing a complex digital dance of stemming, lemmatization, syntactic parsing, and semantic analysis—a machine trying its very best to do what humans do effortlessly: understand language.