Imagine you tell a friend, “Maria isn’t coming to the party tonight.” Your friend, naturally, might ask, “Oh, how do you know?” You’d then have to clarify your source. Did you see her looking unwell earlier? Did she text you? Or did you just hear a rumor from a mutual acquaintance? In English, providing this source of information—your evidence—is a conversational extra. It’s a follow-up, an optional clarification.

But what if it wasn’t optional? What if the way you say “Maria isn’t coming” had to, by the rules of your language, include how you know this? This is the fascinating world of evidentiality: a grammatical system found in many languages where speakers are obliged to specify the source of their knowledge.

So, How Exactly Do You Know That?

In linguistics, evidentiality refers to how languages encode the source of a speaker’s information. For English speakers, this concept feels foreign because we do it lexically. We use separate words and phrases:

- “I saw John leave.” (Direct visual evidence)

- “Apparently, the train is delayed.” (Hearsay/Reported evidence)

- “She must have finished the cake.” (Inferred evidence)

In languages with grammatical evidentiality, this information isn’t conveyed by an extra word but is baked directly into the verb, often as a suffix or particle. It’s not a stylistic choice; it’s a mandatory feature of a well-formed sentence. You can’t just state a fact—you have to state your relationship to that fact. It’s like a built-in citation system for everyday speech.

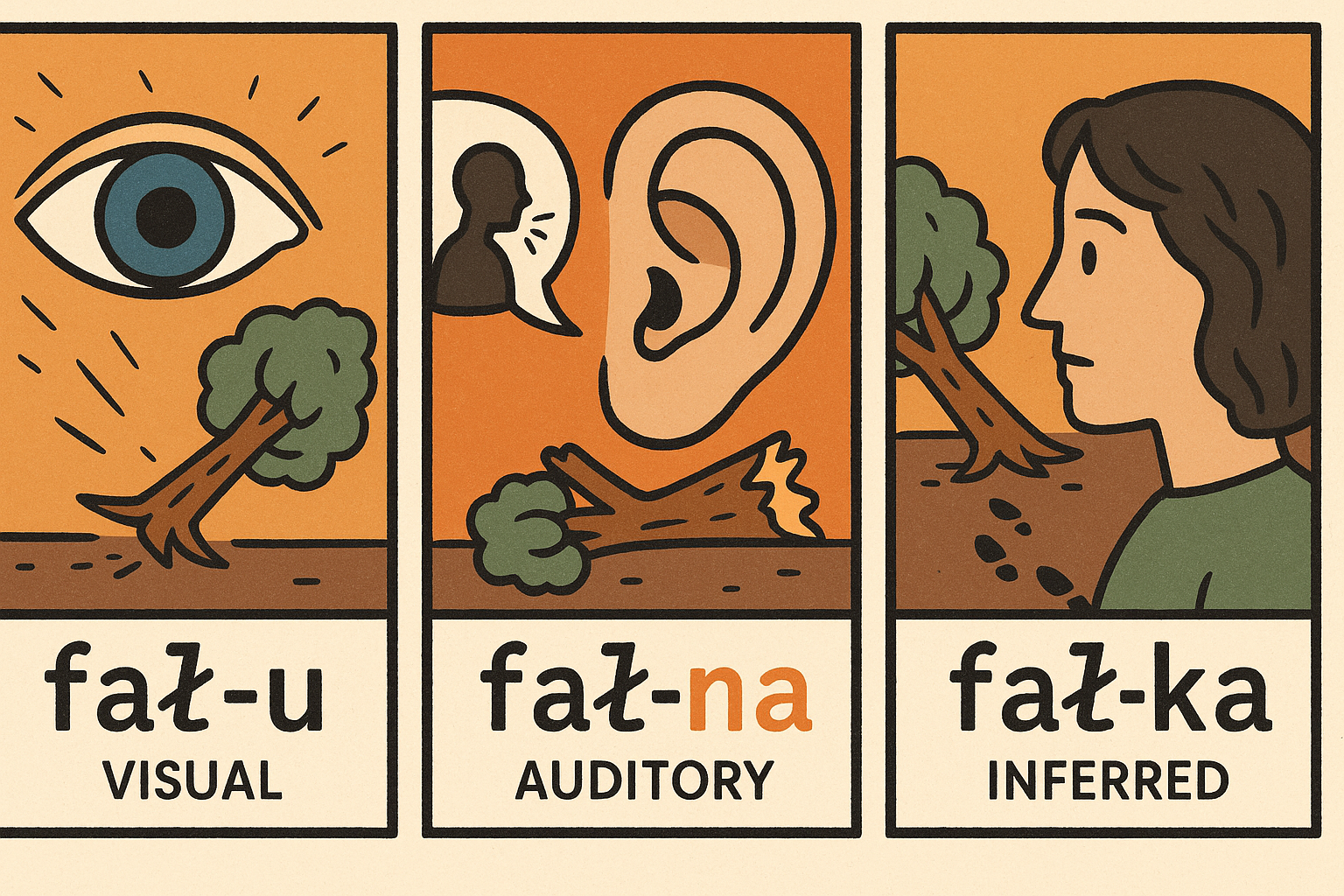

While systems vary, linguists generally identify a few common types of evidential marking:

- Direct/Visual: The speaker personally witnessed the event. This is often considered the most reliable form of evidence.

- Auditory: The speaker heard the event but did not see it (e.g., hearing a crash in another room).

- Inferential: The speaker deduces the information from indirect evidence (e.g., seeing wet streets and inferring it rained).

- Reportative/Hearsay: The speaker was told the information by someone else. This is the basis for rumor, gossip, and storytelling.

A Trip to the Amazon: Eyewitnesses in Tariana

To see how a complex evidential system works, we can travel to the Vaupés River basin in the Amazon, home to the Tariana language. Documented extensively by linguist Alexandra Aikhenvald, Tariana has one of the most cited evidential systems. A speaker of Tariana cannot simply say, “He played soccer.” They must choose an ending for the verb that reflects their knowledge source.

Consider the statement “José played soccer”:

- Juse irida-ka. This ending, -ka, marks visual evidence. It means “I saw José play soccer with my own eyes.” You are making a strong claim based on direct, personal observation.

- Juse irida-mahka. The ending -mahka marks auditory evidence. It translates to “I heard José play soccer.” Perhaps you were inside the house and heard him and his friends shouting and kicking the ball outside.

- Juse irida-sika. This ending, -sika, marks inferred evidence. It means “I infer that José played soccer.” You didn’t see or hear it, but you see him now—he’s sweaty, covered in grass stains, and carrying a soccer ball. The evidence points to a clear conclusion.

- Juse irida-pidaka. Finally, -pidaka marks reported evidence. “Someone told me that José played soccer.” You are relaying information from another source and taking no personal responsibility for its accuracy.

In Tariana, your epistemic status—how you know what you know—is front and center. Lying isn’t just about the content of your statement but also about your claimed evidence. Claiming visual evidence (-ka) for something you only heard about (-pidaka) is a serious grammatical and social mistake.

Gossip and Surprise in the Balkans

Thousands of miles away, a different flavor of evidentiality exists in Balkan languages like Bulgarian, Macedonian, and Turkish. Here, the system is simpler, often boiling down to a two-way distinction: direct, witnessed events versus indirect, unwitnessed events.

In Bulgarian, this is often called the “renarrated mood.” Let’s look at the sentence “He wrote the letter”:

- Toi napisa pismoto. (Той написа писмото.) This uses the simple past tense and implies direct knowledge. “He wrote the letter (and I know this for a fact, perhaps I saw him).” You are committed to the truth of this statement.

- Toi napisal pismoto. (Той написал писмото.) This form is subtly different but carries huge implications. It means “He (apparently/reportedly) wrote the letter.” The speaker is distancing themselves from the claim. They might have heard it from someone else or inferred it from seeing the letter on the table.

This indirect form is famously used for gossip, reporting news, and telling myths and legends—any situation where the speaker isn’t a direct witness. It can also convey surprise. If you thought your friend had already left for vacation, but you see his car outside, you might exclaim in Bulgarian, “Oh! He hasn’t left!” using the indirect form, because you are reporting on a new piece of information that contradicts your previous understanding.

Why Doesn’t English Have This?

If evidentiality is so useful, why don’t all languages have it? English, as we’ve seen, relies on a vast vocabulary of adverbs (“allegedly,” “seemingly”) and modal verbs (“must have,” “might be”) to do the same job. The key difference is obligation.

In English, the neutral, unmarked statement (“It rained”) is the default. Adding an evidential phrase is a choice to provide more detail. In an evidential language, there is no neutral default. You are forced to choose your position. This requirement cultivates a constant, background awareness of epistemology—the philosophy of knowledge. Speakers are perpetually, if subconsciously, asking themselves: How do I know this? And what is my responsibility for this information?

The World Through an Evidential Lens

Evidentiality is more than just a grammatical curiosity. It’s a window into how different cultures structure the very concepts of truth, evidence, and personal responsibility. It reminds us that the tools our language gives us fundamentally shape how we perceive and describe reality.

By forcing speakers to state their evidence, these languages build a framework of accountability directly into their grammar. So the next time you state a simple fact, take a moment to ask yourself the question a Tariana or Bulgarian speaker must answer every time: How do you really know?