Long before the world learned about the spontaneous birth of Nicaraguan Sign Language, a unique linguistic ecosystem thrived on this island off the coast of Massachusetts. This was the home of Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language (MVSL), a complex and complete language that emerged not in a school or an institution, but organically from the needs of a community where deafness was simply a part of the local fabric.

A Crucible of Communication: The Origins of Deafness

The story of MVSL begins with a classic case of the “founder effect.” In the late 17th century, a small group of English colonists, primarily from the Weald of Kent, settled the island. Unbeknownst to them, some of these founding families carried a recessive gene for hereditary deafness (a syndrome now identified as Usher Syndrome type 3 or a variant of DFNB1).

In the relative isolation of island life, these settlers intermarried, and the recessive gene became unusually common. As a result, the rate of deafness on Martha’s Vineyard was astonishingly high. While the national average was roughly 1 in 5,700, on the Vineyard it was 1 in 155. In some of the more isolated up-island towns like Chilmark and West Tisbury, the rate soared to as high as 1 in 25 people. In some families, entire generations of children were born deaf.

This high incidence created a critical mass. Deafness wasn’t a rare affliction affecting a single isolated individual; it was a shared family and community experience. A robust method of communication was not just a convenience—it was a necessity.

An Island Where Everyone Spoke Sign

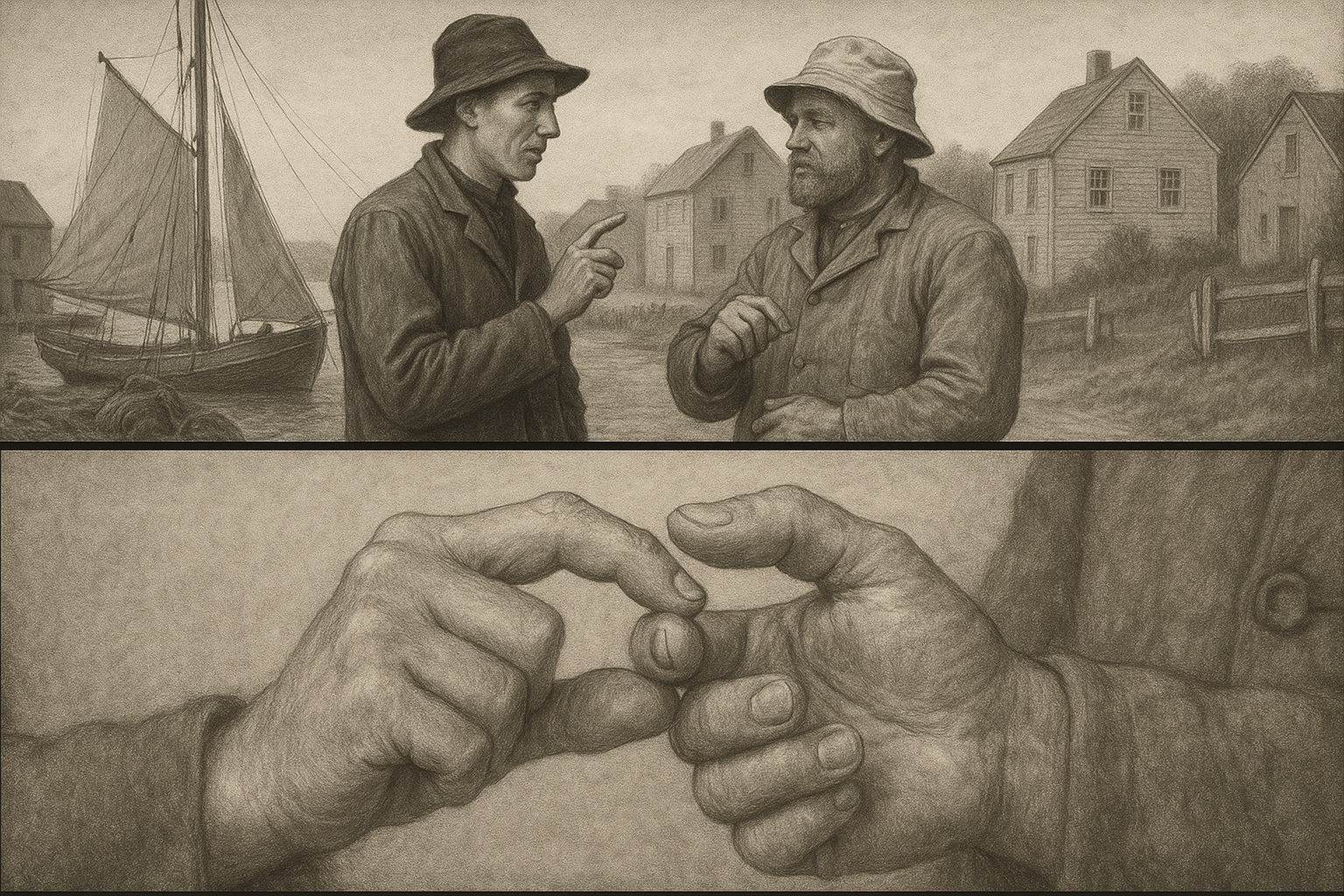

What made the Vineyard truly remarkable was not the deafness itself, but the community’s response to it. Instead of isolating or pitying their deaf neighbors, hearing islanders adapted. Virtually everyone in the community became bilingual, speaking English and signing MVSL. Hearing children grew up learning MVSL from their deaf relatives, friends, and neighbors just as naturally as they learned spoken English.

This bilingualism had a profound impact on the island’s culture. Deafness was not viewed as a disability or a barrier to participation. Deaf islanders were fully integrated into the economic and social life of the community. They worked, owned property, paid taxes, held public office, and married whomever they chose, deaf or hearing. The language belonged to everyone, and its use was widespread:

- Farmers could sign to each other across wide fields.

- Worshippers could follow a church sermon even if they sat in the back, as others would sign the key points.

- Deaf and hearing people could gossip, tell stories, and argue at town meetings without missing a beat.

- Hearing people often used MVSL among themselves, especially in situations where speech was impractical—across a noisy room, from a distance, or when they needed to be quiet.

As linguist Nora Ellen Groce noted in her seminal book, Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language, the key was that communication was always possible. If you were talking to a group and a deaf person approached, the conversation didn’t stop; it simply shifted to sign, including everyone seamlessly.

The Language Itself: More Than Just Gestures

MVSL was not a crude system of pantomime or a signed version of English. It was its own distinct language with a unique grammar and lexicon. While it was never formally written down in its prime, research conducted in the 1970s with its last elderly users revealed a rich and systematic language. It is believed to have roots in an unrecorded sign language used in the Kentish Weald in England, brought over by the original settlers and adapted over generations on the island.

It had signs for local people, island geography, and the specific activities of a fishing and farming community. MVSL also used a two-handed alphabet for fingerspelling, unlike the one-handed system used in modern American Sign Language (ASL).

The Inevitable Silence: The Decline of MVSL

So, where did this unique language go? By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the island’s isolation began to erode. Steamboats brought more “off-islanders” to visit, work, and settle. As islanders began to marry people from the mainland, the hereditary deaf gene pool was diluted, and the rate of deafness began to fall to national norms.

Simultaneously, formal education for the deaf was becoming established on the mainland. Instead of being educated within their signing community, children from the Vineyard were sent to institutions like the American School for the Deaf (ASD) in Hartford, Connecticut. There, they were exposed to a different, rapidly developing sign language that was being codified from a mix of home signs and, most significantly, French Sign Language (LSF).

From Vineyard Shores to a National Language: MVSL’s Lasting Echo

The story of MVSL doesn’t end with its decline. It has a powerful and enduring legacy. When the students from Martha’s Vineyard arrived at the American School for the Deaf, they brought their fluent, systematic language with them. They didn’t arrive with a handful of “home signs” like many other students; they brought a fully-formed language.

Linguists now know that MVSL was one of the primary languages that blended with French Sign Language and other regional signs to form the creole that we now call American Sign Language (ASL). MVSL is, in essence, one of the parent languages of ASL. Its vocabulary, structure, and inherent fluency contributed significantly to the formation of the language used by hundreds of thousands of people today.

The last native user of MVSL, a woman named Katie West, passed away in 1952. With her, the language as a living, community-wide phenomenon ceased to exist. But its spirit and its linguistic DNA live on in every conversation held in ASL.

A Lesson in Inclusion

The story of Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language is more than a linguistic curiosity. It is a profound testament to human adaptability and the social construction of disability. On the Vineyard, deafness was not an impairment because the community collectively removed the barriers to communication. MVSL stands as a powerful, historical example of how a community, through its language, can create a world of genuine, effortless inclusion.