Picture a comic book panel. A hero stands defiantly, a sharp-angled speech bubble erupting from their mouth. In the background, stylized letters scream “KRAK-A-THOOM!” as a building crumbles. Every element in this single frame—the character’s posture, the shape of the bubble, the text within it, and the sound effect woven into the art—works in concert to tell a story. Now, imagine the task of taking this intricate tapestry and reweaving it in a different language.

Translating a comic or graphic novel is one of the most uniquely constrained and creative fields in linguistics. It goes far beyond the dictionary. A comic translator isn’t just working with words; they are working with space, rhythm, art, and culture. They operate in the subtle, often invisible space between panels—the “gutter”—where a reader’s mind makes connections. To do their job well, they must be part linguist, part artist, and part visual storyteller, navigating a minefield of challenges that would never occur in a standard prose novel.

The Tyranny of the Speech Bubble

The most immediate and unforgiving constraint for a comic translator is the speech bubble. Unlike a novel, where a sentence can be expanded for clarity or stylistic effect, a comic’s dialogue must fit into a pre-drawn, unchangeable space. This creates a fascinating linguistic puzzle.

Languages are not created equal in terms of length. A concise English phrase like “Get out!” might become the more verbose “¡Sal de aquí ahora mismo!” in Spanish or “Gehen Sie sofort raus!” in German. This phenomenon, known as “text expansion” (or contraction), is a translator’s constant battle. They must find a translation that is not only accurate in meaning and tone but also physically fits. This often requires brilliant, creative solutions:

- Finding a more concise synonym or idiom.

- Restructuring the sentence to be punchier.

- Sometimes, slightly altering the meaning to preserve the flow and fit the space, a compromise that literary translators would rarely have to consider.

The translator must also consider the work of the letterer—the person who physically places the new text into the artwork. A clunky, overly long translation can force the letterer to shrink the font to an unreadable size or cram words together, destroying the visual balance of the panel. The best translations feel as if they were the original text all along.

Speaking in Sounds: The Onomatopoeia Conundrum

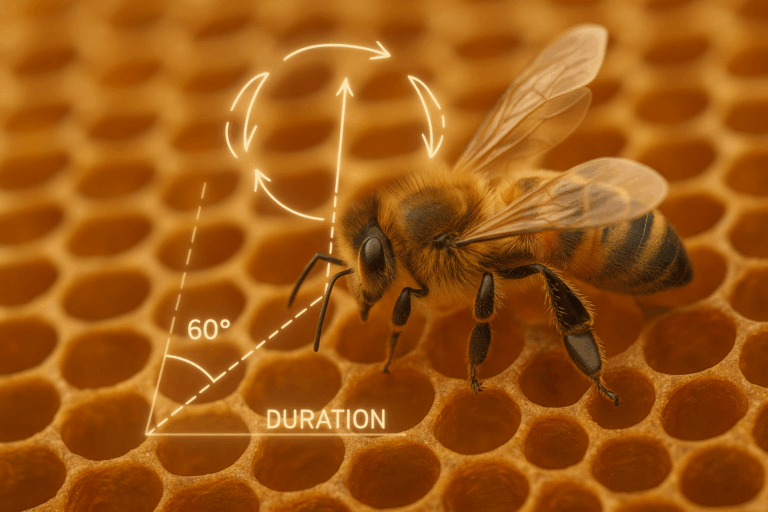

What sound does a dog make? In English, it’s “woof.” In Japanese, “wan wan” (ワンワン). In French, “ouaf ouaf.” Sound effects, or onomatopoeia, are deeply ingrained in culture and language. In comics, they are more than just words; they are an integral part of the artwork, often hand-drawn by the artist to convey motion, impact, and emotion.

This presents the translator with a difficult choice. Take the iconic Japanese sound effect for a dramatic reveal or impact: “ドーン” (DŌN). Do you:

- Keep the original? This is common in manga translations. It preserves the artist’s original work and aesthetic, but it can alienate readers unfamiliar with the source language. Often, a small gloss is added in the margin or near the effect.

- Translate it? The translator could replace “DŌN” with a culturally equivalent effect like “BAM!” or “THOOM!” This makes it immediately understandable but requires a skilled letterer to recreate the effect in a new style that matches the original art. It is a form of artistic intervention.

- Remove it entirely? This is rarely a good option, as it strips a layer of meaning and energy from the panel.

The decision depends on the publisher, the target audience, and the overall artistic intent. There is no single right answer, and each choice has a profound impact on how the reader experiences the story’s soundscape.

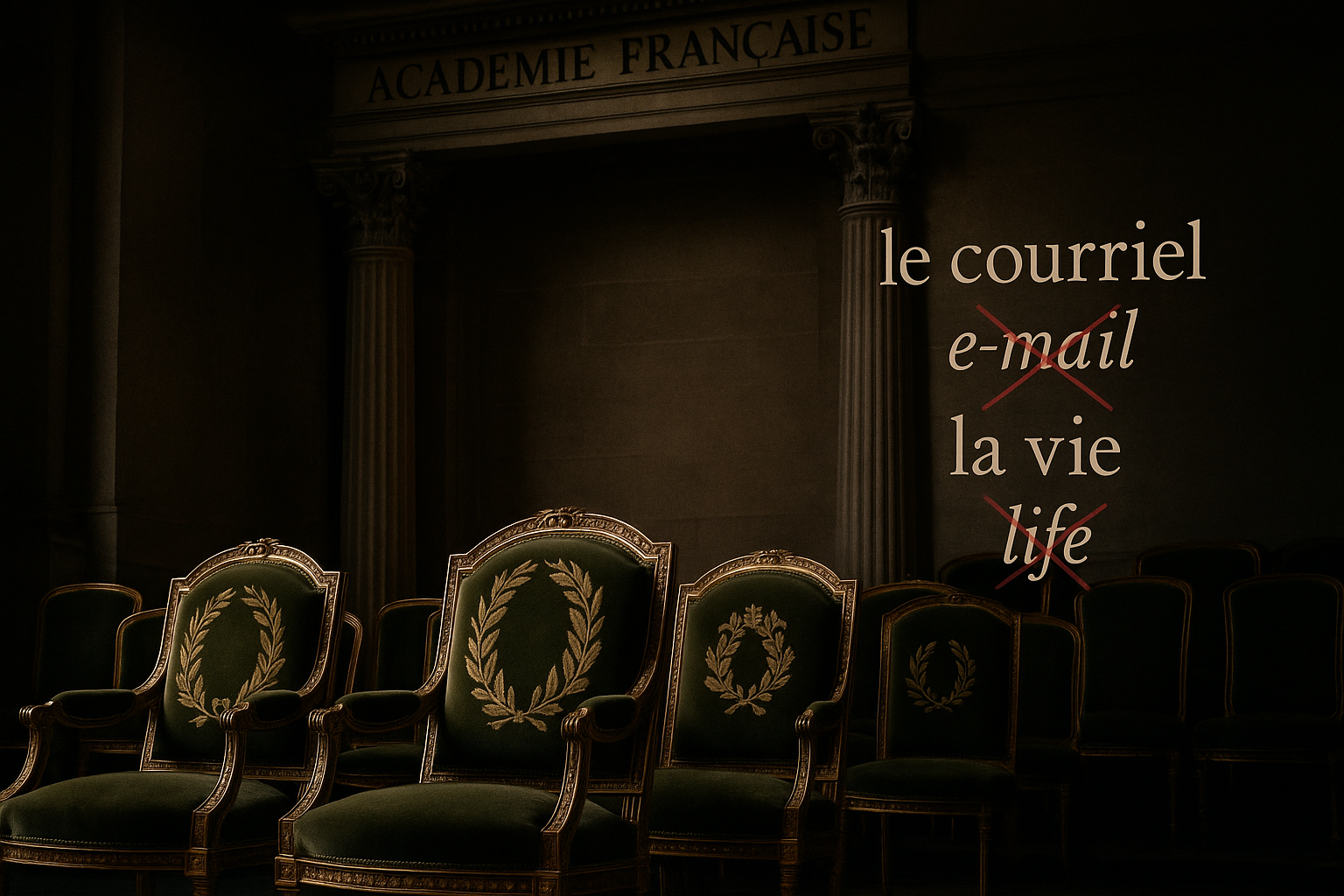

Reading Between the Lines: Cultural and Visual Translation

The most subtle and perhaps most difficult challenge lies in translating the visual language of the comic itself. The art is not universal; it is packed with cultural symbols, gestures, and contexts that may be obvious in one culture and opaque in another.

Consider these examples:

- Gestures: A character giving a “thumbs up” is generally positive in the West, but it can be an offensive gesture in parts of the Middle East and West Africa. A translator must be aware of this, potentially adding a line of dialogue to clarify the character’s intent if the gesture could be misinterpreted.

- Symbolism: A bento box in a Japanese school manga isn’t just lunch; it can be a symbol of a mother’s love, a character’s domestic skills, or their social isolation. A direct translation might miss this subtext. The translator might need to subtly guide the reader or, in some cases, a small explanatory note might be included.

- Reading Direction: This is the classic challenge of manga translation. Japanese comics are read right-to-left. For decades, Western publishers would “flip” the artwork to a left-to-right orientation. This was a costly process that created bizarre visual errors—swords were suddenly worn on the wrong side, characters who were left-handed became right-handed, and text on signs or shirts appeared reversed. Today, most publishers preserve the original right-to-left format, trusting the audience to adapt. This decision itself is a form of translation—translating a reading experience rather than just the content.

The Translator as a Silent Storyteller

Ultimately, a comic translator’s goal is to recreate an experience. They must preserve the delicate timing of a page-turn reveal, the rhythm of banter between characters, and the emotional impact of a silent panel. A translation that is technically perfect but feels clunky or out of sync with the art has failed.

They are the silent partner to the writer and the artist. Their work exists in the background, ensuring that the story’s journey across linguistic and cultural borders is as seamless as the reader’s eye moving from one panel to the next. So the next time you pick up a translated graphic novel, take a moment to appreciate the invisible artist at work—the translator lost in the gutter, carefully piecing a world back together, one bubble at a time.