What’s in a name? When it comes to disease, the answer is: a whole lot of history, a dash of fear, and a hefty dose of politics. The label we affix to an ailment is never truly neutral. It’s a linguistic fingerprint, revealing as much about the people who named it as the pathology itself. From the “bad air” of malaria to the clinical precision of COVID-19, the journey of disease naming is a fascinating look at how science, culture, and language intersect to define our greatest microscopic foes.

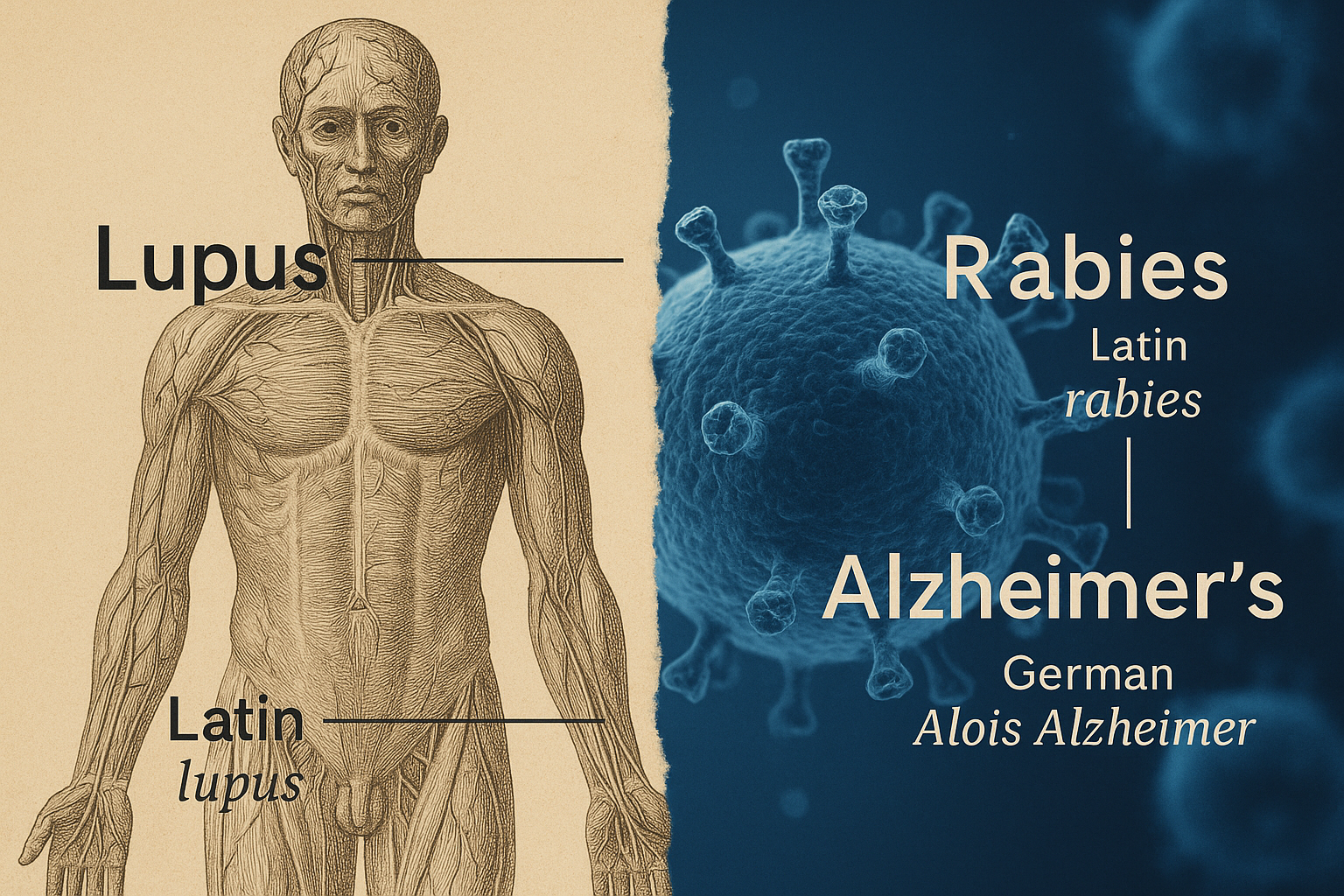

The Classical Lexicon: Building Blocks of Pathology

Step into any medical school, and you’ll be immersed in a world of Latin and Greek. This isn’t just academic gatekeeping; it’s a legacy of the classical world’s foundational role in Western medicine. Ancient physicians like Hippocrates and Galen laid the groundwork, and their languages provide a universal, descriptive shorthand for doctors worldwide.

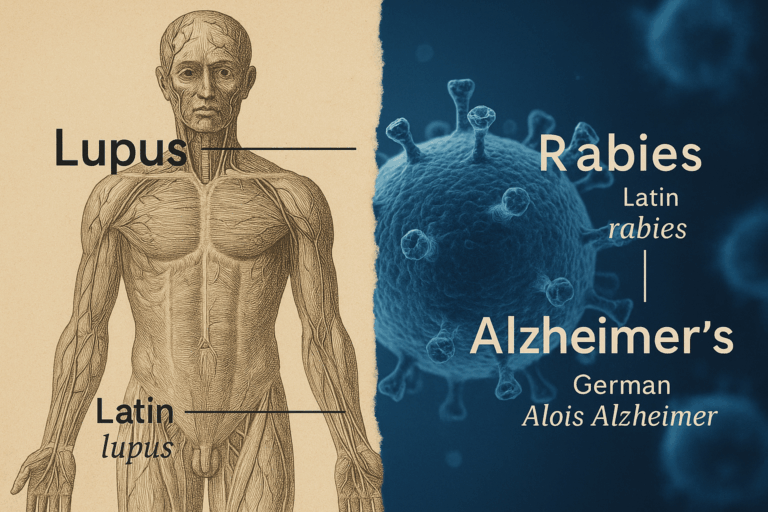

The most famous suffix is likely -itis, a Greek gift meaning “inflammation.” Attach it to a root word, and you instantly know the core of the problem. Bronchitis? Inflammation of the bronchial tubes (from the Greek bronkhos). Arthritis? Inflammation of the joints (arthron). Hepatitis? Inflammation of the liver (hepar). This elegant system turns complex conditions into logical, digestible terms.

The entire body is a map of these classical roots. Cardio (heart), nephro (kidney), and derma (skin) are all Greek. Other names are beautifully descriptive. Diabetes mellitus, for instance, sounds complex, but its Latin and Greek roots translate to “siphon” and “honey-sweet.” Early physicians diagnosed it by tasting a patient’s urine, which was unusually sweet—a hauntingly poetic name for a metabolic disorder.

From Bad Air to the King’s Evil: When Names Tell a Story

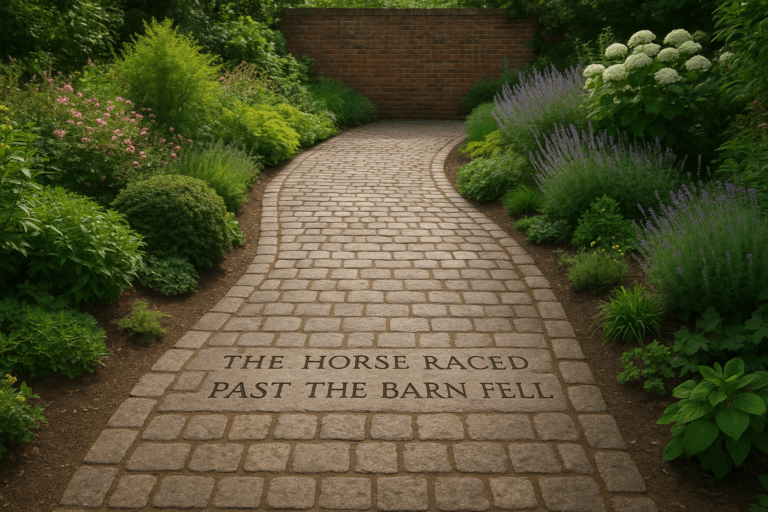

Before the germ theory revolutionized medicine in the 19th century, diseases were often named for what people believed caused them, how they manifested, or even the superstitions surrounding them. These names are historical artifacts, preserving outdated theories and cultural beliefs.

Consider malaria. For centuries, people living near swamps were afflicted by a deadly fever. The culprit seemed obvious: the foul-smelling air rising from the stagnant water. The Italians named it mal’aria—literally, “bad air.” The name stuck, even after we discovered its true cause was a parasite transmitted by mosquitos that breed in that same water. The name is a fossil, preserving the miasma theory of disease for all time.

Other names reflect social structures. Scrofula, a form of tuberculosis affecting the lymph nodes in the neck, was known for centuries in England and France as “The King’s Evil.” The name came from the widespread belief that a touch from a legitimate monarch could cure the affliction. Here, the name isn’t about pathology but about divine right and royal power.

Even a name as evocative as the Black Death tells a story. While some scholars connect it to the dark, gangrenous sores (buboes) that appeared on victims, it also powerfully captures the metaphorical darkness and devastation the plague cast over 14th-century Europe.

The Politics of Place: Stigma and the Eponym

As our understanding of pathogens grew, a new naming convention emerged: tying a disease to the place it was first identified or the person who discovered it. While seemingly logical, this practice is fraught with peril.

Place-based names, or toponyms, can be disastrous. The 1918 influenza pandemic is widely known as the “Spanish Flu,” a deeply misleading name. The virus likely didn’t originate in Spain, but as a neutral country in World War I, its press was free to report on the devastating outbreak, while censored newspapers in warring nations kept quiet. The name unfairly stigmatized Spain and set a dangerous precedent. We’ve seen it repeated with West Nile Virus, Lyme Disease (from Lyme, Connecticut), and Ebola (named after the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of Congo).

These names can cause real harm. They can fuel xenophobia, devastate tourism and trade, and lead to the shunning of entire populations, who are blamed for a biological accident of geography.

Naming a disease after a person—an eponym—is also problematic. While names like Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease honor their pioneering researchers, they tell us nothing about the condition itself. Worse, they can become toxic if the namesake’s legacy is tarnished. Reiter’s syndrome, named for the Nazi physician Hans Reiter who conducted horrific human experiments, is now increasingly referred to by the descriptive term “reactive arthritis” for this very reason.

The Modern Mandate: Naming COVID-19

Recognizing these dangers, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued formal guidelines in 2015 for naming new human infectious diseases. The goal was to create a system that is scientific, objective, and socially responsible. The rules are clear:

- Do not include geographic locations (e.g., Spanish Flu, Zika).

- Do not include people’s names (e.g., Chagas disease).

- Do not include species of animal or food (e.g., Swine Flu, Monkeypox).

- Do not include cultural or occupational references (e.g., Legionnaires’ disease).

- Avoid terms that incite undue fear (e.g., “fatal,” “epidemic”).

Instead, names should be descriptive and based on the science. They should include the causative pathogen, the symptoms, the severity, and other objective facts.

The first major test of this new system came in late 2019. As a novel coronavirus spread across the globe, the pressure for a name was immense. Unofficial, stigmatizing terms like “Wuhan virus” began to circulate, threatening to derail the global response with political blame-games.

On February 11, 2020, the WHO announced the official name:

COVID-19

It was a perfect example of the new guidelines in action:

- CO for “corona”

- VI for “virus”

- D for “disease”

- 19 for 2019, the year the outbreak was first identified.

The name is clinical, informative, and neutral. It describes what the disease is without attaching it to any place, animal, or group of people. It was a deliberate act of linguistic public health, designed to foster cooperation, not conflict.

Language is more than a tool for communication; it’s a framework for our understanding. The names we choose for diseases can either spread fear and stigma or promote clarity and collaboration. From the bad air of our ancestors to the calculated neutrality of today, the evolution of disease naming shows us that in the fight against our invisible enemies, words are one of our most powerful weapons.