Take a moment and look at the sky on a clear day. What color do you see? You’d probably say “blue.” Now look at a pair of denim jeans, or the color of a blueberry. Again, most English speakers would call it “blue.” But is the “blue” you see the same “blue” that a Russian, a Greek, or an ancient Homeric poet would see? The answer, fascinatingly, is no. The language you speak doesn’t just give you words to describe the world; it actively shapes how you perceive it.

This mind-bending idea is at the heart of one of linguistics’ most captivating theories, and the world of color provides the most vivid evidence for it.

The Lens of Language: Introducing Sapir-Whorf

The idea that language can influence thought is known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, named after linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf. This hypothesis exists on a spectrum:

- Linguistic Determinism (The “strong” version): This is the radical idea that language determines thought. It suggests that the boundaries of your language are the boundaries of your world, and you simply cannot conceive of things you don’t have words for. This version is now largely discredited.

- Linguistic Relativity (The “weak” version): This is the more nuanced and widely accepted view. It proposes that language influences thought, perception, and memory. The language you speak can make you pay more attention to certain details, categorize things differently, and process information more efficiently in some areas than others.

Think of it like this: language is not a prison for the mind, but rather a set of cognitive tools or a lens. It can focus your attention on certain distinctions, making them more salient and easier to process. Nowhere is this clearer than in our perception of color.

A Tale of Two Blues: The Russian Experiment

Let’s return to the color blue. In English, we have one basic word, “blue,” and we use modifiers to describe its shades (light blue, dark blue, navy blue, sky blue). But in Russian, there are two distinct, basic words for what we call blue:

- Goluboy (голубой): Used for light blue.

- Siniy (синий): Used for dark blue.

To a Russian speaker, goluboy and siniy are as different as red and pink are to an English speaker. So, does this linguistic difference translate to a perceptual one? Cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky and her colleagues designed a brilliant experiment to find out.

They showed native Russian and English speakers three squares on a screen—one on top and two on the bottom. The top square matched one of the bottom squares, and participants had to press a button to indicate which one as quickly as possible. Sometimes, the two bottom squares were both shades of goluboy or both shades of siniy. Other times, one was goluboy and the other was siniy.

The results were striking. Russian speakers were significantly faster at distinguishing between the two shades when they fell into different linguistic categories (one goluboy, one siniy) than when they were from the same category. English speakers, who call both shades “blue,” showed no such speed advantage.

This suggests that having a dedicated word for each category primes the brain, making the distinction more obvious and the decision quicker. The language itself provides a cognitive shortcut.

When Blue Is Green: The Himba and the Color Spectrum

The story gets even more compelling when we look at cultures with radically different color systems. The Himba people of northern Namibia have a fascinating vocabulary for color. Their language has no separate word for “blue.” Instead, the shades we would call blue are grouped under their words for green. However, they have multiple distinct words for shades of green that look nearly identical to a non-Himba observer.

In another famous experiment, researchers showed Himba participants a circle of green squares with one blue square mixed in. To an English speaker, the blue square pops out almost instantly. For the Himba, it was a slow, difficult task. Many couldn’t find the different square at all.

But here’s the crucial part: the researchers then reversed the test. They showed participants a circle of squares that all looked green to an English speaker, but one of them was a shade of green for which the Himba have a unique word. This time, the Himba participants spotted the different square with ease, while English speakers struggled to see any difference at all.

This powerfully demonstrates that the Himba aren’t “color deficient”; their language has simply trained their brains to be highly sensitive to the green distinctions that are relevant in their environment, while ignoring the green-blue distinction that is less important.

The Colorless Past: Homer’s “Wine-Dark Sea”

This phenomenon isn’t just cross-cultural; it’s also historical. In the 19th century, British scholar William Gladstone (who later became Prime Minister) noticed something odd while studying Homer’s Odyssey. The ancient Greek text was filled with vivid descriptions of black, white, and metallic colors, with some mentions of red and yellow. But one color was conspicuously absent: blue.

Homer famously described the sea not as blue, but as “wine-dark” (oinops pontos). The sky was rarely described by color, but rather by its brightness. It wasn’t just Homer. Scholars found that other ancient texts, from the Icelandic sagas to the Hebrew Bible, also lacked a word for blue.

Did ancient people not see blue? It’s highly unlikely their vision was different. The modern consensus is that this reflects a universal pattern in how languages develop color terms. Basic color terms almost always emerge in a predictable order:

- Black and White (dark/light)

- Red

- Green or Yellow

- Yellow or Green

- Blue

Blue is often last because it’s relatively rare in the natural world. Apart from the sky (which is an intangible expanse, not an object) and a few flowers and minerals, there aren’t many things that require a dedicated word for blue. The need for the word—and thus, the cultural recognition of the category—only became widespread after humans developed the technology to create stable blue pigments.

A World of Many Colors

So, does your language determine what your eyes physically see? No. A Russian speaker’s retinal cones are the same as an English speaker’s. The difference is cognitive. Language acts as a filter or a guide, training your brain to build categories and pay attention to the boundaries between them.

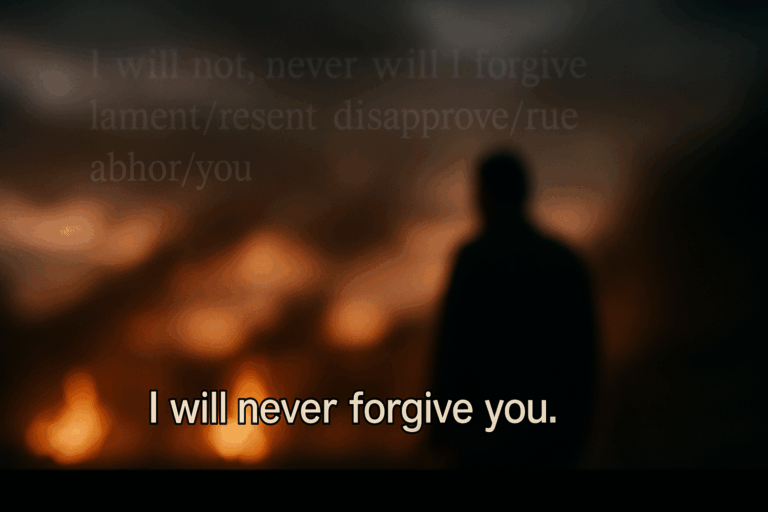

Having a word for something makes it a “thing.” For Russian speakers, goluboy is a thing and siniy is a thing. For the Himba, a specific shade of grass-green is a thing. For ancient Greeks, the category of “blue” simply wasn’t a thing yet.

This research doesn’t just tell us about color; it tells us about the profound connection between language, culture, and cognition. It reveals that the words we use are more than simple labels. They are the scaffolding upon which we build our understanding of reality. Learning another language, then, is not just about memorizing new vocabulary; it’s about gaining access to a new way of seeing, a new way of thinking, and a subtly different version of the world.