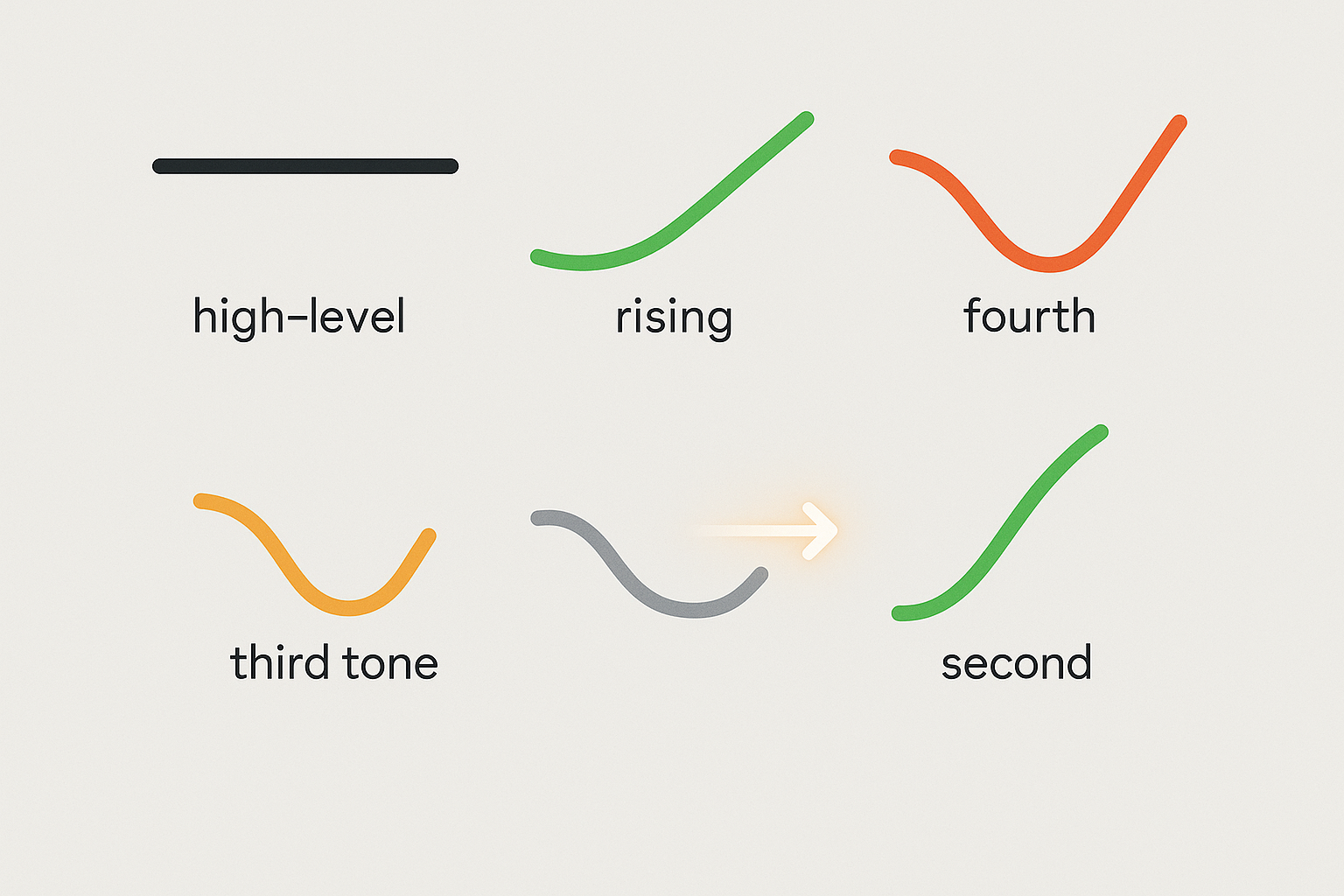

If you’ve ever dipped your toes into the vast ocean of Mandarin Chinese, you’ve undoubtedly been introduced to its four famous tones. You diligently practice them: the high and level first tone (mā), the rising second (má), the dipping-and-rising third (mǎ), and the sharp, falling fourth (mà). You learn that getting the tone right is the difference between complimenting someone’s mother (mā) and calling them a horse (mǎ).

Then, you encounter one of the most common greetings in the world: 你好 (nǐ hǎo), or hello. You know that nǐ (你) is a third tone, and hǎo (好) is also a third tone. You carefully pronounce them back-to-back: a dip, a rise, another dip, another rise. It feels clunky, slow, and unnatural. And when you listen to a native speaker, you hear something completely different. The first syllable, nǐ, sounds suspiciously like a rising second tone: ní hǎo.

Was your teacher wrong? Is your textbook full of lies? No. You’ve just stumbled upon one of the most fascinating and fundamental features of Mandarin phonology: tone sandhi, the chameleon-like process where tones change to create a more fluid, musical, and natural-sounding language.

What Exactly is Tone Sandhi?

The term “sandhi” comes from Sanskrit and means “joining” or “placing together.” In linguistics, it refers to the process where the sounds of words or syllables change based on their neighbors. We even have a version of this in English, though we don’t think about it. We say “an apple” instead of “a apple” because it’s easier to transition from the “n” sound to the vowel “a.”

In Mandarin, this principle is applied to tones. Tone sandhi is not a collection of random exceptions; it’s a systematic set of rules that governs the prosody—the rhythm and melody—of connected speech. It’s the language’s way of smoothing out the phonetic bumps in the road, ensuring a graceful flow from one syllable to the next. And the most famous, most common, and most important of these rules involves the tricky third tone.

The Star of the Show: The Third Tone Transformation

The third tone (e.g., mǎ) is phonetically the most complex of the four. It requires your vocal cords to perform a dip followed by a rise. While manageable on its own, saying two of these back-to-back is like asking a dancer to perform two complex dips in a row without a transitional step—it’s awkward and breaks the rhythm.

To see why, try it yourself. Say “hǎo” (good) with its full dipping-rising contour. Now, try to say “hǎo hǎo” (very good). You can feel the vocal gymnastics required. It’s slow and cumbersome.

Mandarin solves this problem with an elegant rule:

When two third-tone syllables appear consecutively, the first one changes to a second (rising) tone.

Let’s revisit our hello:

- 你好 (nǐ hǎo): Individually, they are third tone + third tone.

- In practice, it becomes ní hǎo: second tone + third tone.

This change transforms a clunky “dip-rise + dip-rise” into a smooth “rise + dip-rise” contour. It’s the path of least resistance for the vocal cords and creates a much more pleasant melody. This isn’t just a slight modification; it’s a complete tonal shift that is obligatory in standard Mandarin.

More Examples in the Wild

Once you know this rule, you’ll start hearing it everywhere:

- 水果 (shuǐguǒ) – fruit. The tones are 3 + 3, but it’s always pronounced shuíguǒ (2 + 3).

- 可以 (kěyǐ) – can / may. The tones are 3 + 3, but you’ll hear it as kéyǐ (2 + 3).

- 我想 (wǒ xiǎng) – I want to. The tones are 3 + 3, so it’s pronounced wó xiǎng (2 + 3).

The Plot Thickens: The “Half-Third” Tone

To add another layer to its chameleon nature, a third tone often doesn’t even complete its full “dip-rise” when it stands alone or at the end of a phrase. Instead, it’s pronounced as a “half-third tone”—a low, creaky sound that just dips without the final rise. For example, in the word 我 (wǒ), meaning I, you’ll often just hear the low dip.

This is crucial in longer phrases. Consider 我很好 (wǒ hěn hǎo), meaning I am very good. Here we have a sequence of three third tones!

- The original tones are: wǒ (3) + hěn (3) + hǎo (3).

- Applying the sandhi rule, the middle syllable changes: wǒ (3) + hén (2) + hǎo (3).

- In actual speech, the first wǒ is pronounced as a half-third tone (just the dip), followed by the rising hén, and finally the full third-tone hǎo.

The result is a beautiful, wave-like melodic contour that is far more natural than three consecutive dips and rises. It’s the language optimizing itself for fluency.

Beyond the Double Third: Other Sandhi Surprises

While the third-tone rule is the most prominent, it’s not the only chameleon in the Mandarin zoo. The tones of two of the most common characters in the language, 一 (yī) and 不 (bù), are also famously shifty.

The Many Tones of 一 (yī – one)

- When alone, as a number, or at the end of a word, it’s a first tone (yī).

- When it comes before a fourth tone syllable, it changes to a second tone (yí). Example: 一样 (yíyàng) – the same.

- When it comes before a first, second, or third tone syllable, it changes to a fourth tone (yì). Example: 一天 (yìtiān) – one day.

The Fickle Nature of 不 (bù – not/no)

- Usually, it’s a fourth tone (bù). Example: 不好 (bù hǎo) – not good.

- However, when it precedes another fourth tone, it changes to a second tone (bú) to avoid the awkwardness of two sharp falling tones in a row. Example: 不是 (búshì) – is not.

Unlocking the Musical Logic

At first, tone sandhi can feel like a frustrating layer of complexity for learners. It seems like the language is breaking its own rules. But understanding the “why” behind it transforms it from a tedious rule to memorize into a key that unlocks the language’s inner logic.

Tone sandhi exists for one primary reason: articulatory efficiency. It’s the linguistic equivalent of finding the most comfortable and energy-efficient way to walk. It smooths out the journey, creating a rhythmic and melodic flow that is essential to sounding like a native speaker.

For language learners, the lesson is clear: don’t just learn tones in isolation. Listen to how they are strung together in phrases and sentences. Imitate the flow and melody of native speakers. Once you internalize the rhythm of tone sandhi, you’ll find your own pronunciation becoming more natural, more fluid, and more confident.

For lovers of language and linguistics, tone sandhi is a perfect illustration of how a language’s abstract rules (phonology) are beautifully constrained by the physical realities of producing speech (phonetics). It’s a reminder that language isn’t just a static system of symbols and sounds, but a dynamic, living entity that constantly optimizes itself for communication. The chameleon tone isn’t a quirk; it’s a stroke of phonological genius.