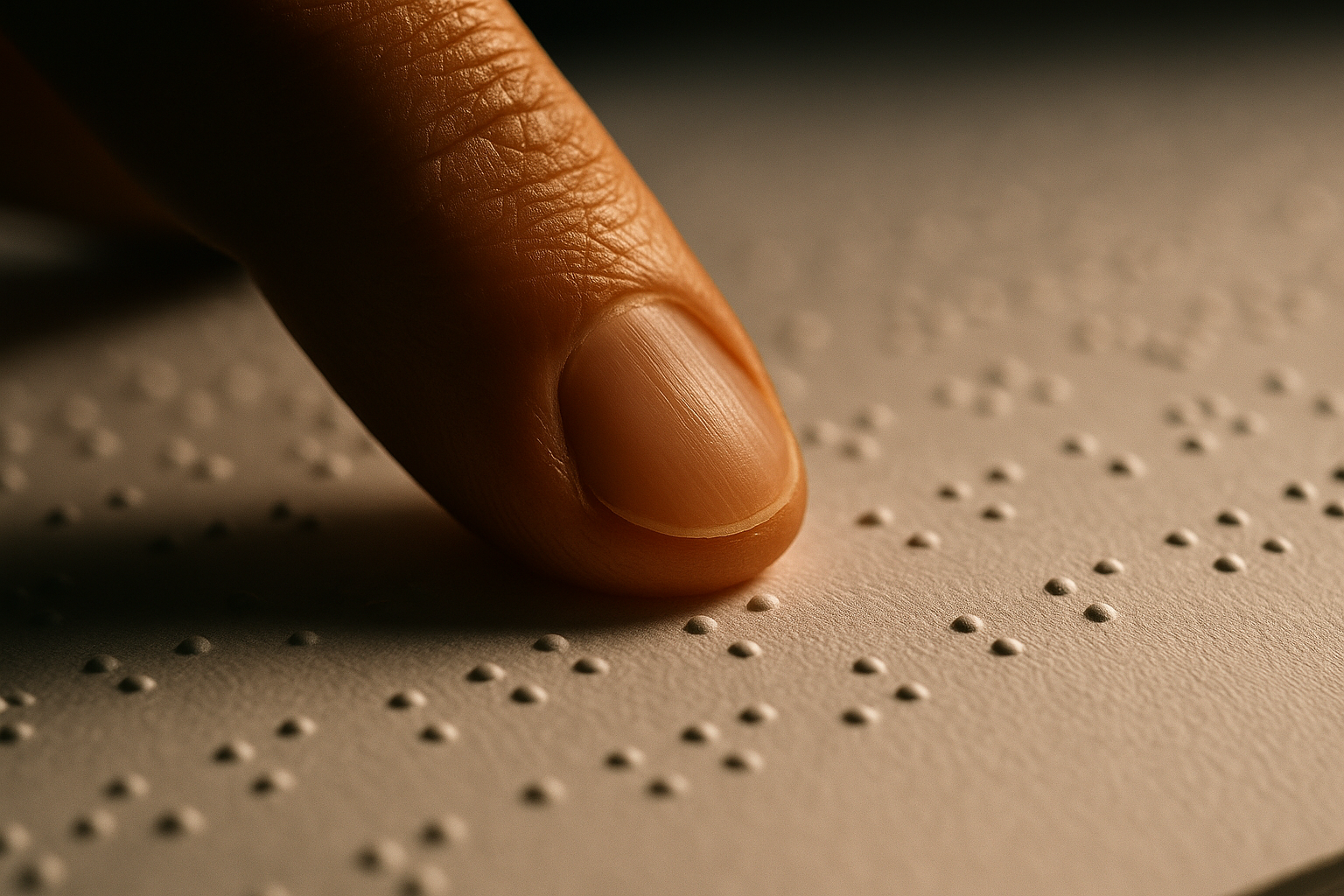

In the vast tapestry of human communication, we often focus on the languages we speak and the scripts we see. But what if a language wasn’t meant for the eyes or the ears, but for the fingertips? This is the story of Braille, a revolutionary tactile writing system that is far more than a simple substitution for the Latin alphabet. It is a work of linguistic genius, a code of touch that granted literacy, independence, and a universal voice to millions.

To understand the profound impact of Braille, we must first imagine a world without it. For centuries, blindness was almost synonymous with illiteracy, a sentence to a life of dependence and intellectual isolation.

A World Before Braille: The Darkness of Illiteracy

Before the 19th century, attempts to create reading systems for the blind were clumsy and impractical. The most common method, championed by Valentin Haüy, involved embossing Latin letters onto heavy paper. Imagine trying to read by tracing the familiar shapes of A, B, and C with your fingers. It was slow, cumbersome, and incredibly difficult to distinguish between similar shapes like ‘O’ and ‘Q’ or ‘M’ and ‘N’.

Furthermore, writing in this system was virtually impossible for a blind person. The books were enormous, expensive to produce, and offered a reading experience that was more frustrating than enlightening. These systems were designed by sighted people for the blind, failing to consider the unique capabilities of tactile perception. They were a translation of a visual world, not a system native to the sense of touch.

The Spark of Inspiration: From Night Writing to a New Dawn

The revolution began, as it often does, with one brilliant and determined individual: Louis Braille. Blinded in a childhood accident at the age of three, Braille was a gifted student at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris. He experienced the deep frustration of the raised-letter system firsthand and yearned for a way to read and write as fluidly as his sighted peers.

In 1821, a French army captain named Charles Barbier de la Serre visited the institute. He presented his invention, “night writing” (sonographie), a system designed for soldiers to communicate silently in the dark without a light source. Barbier’s system used a grid of 12 raised dots to represent phonetic sounds, not letters. A single fingertip could, in theory, feel the entire symbol at once.

While the institute’s leaders dismissed the system as too complex, the teenage Louis Braille saw its raw potential. He recognized the genius of using dots instead of lines, but he also identified its fatal flaws. The 12-dot cell was too large to be perceived by a single fingertip without moving it, slowing down reading. Crucially, because it was phonetic, it couldn’t represent orthography—spelling, punctuation, and numbers—which are essential for true literacy.

Cracking the Code: The Genius of the Six-Dot Cell

Over the next few years, working tirelessly with an awl and slate, Braille refined, simplified, and systematized Barbier’s concept. His breakthrough was reducing the 12-dot cell to a simple 2×3 grid of six dots. This compact cell, no taller than a fingertip, could be read instantly. With this foundation, he built an entire logical system.

The 64 possible combinations (2⁶) provided more than enough characters for his purpose. The organization is a model of linguistic elegance:

- The First Decade (Letters A-J): These form the foundation, using only the top four dots (1, 2, 4, 5).

- The Second Decade (Letters K-T): These are simply the first decade with dot 3 added to each character. (e.g., A is dot 1; K is dots 1 and 3).

- The Third Decade (Letters U, V, X, Y, Z): These are the first five letters (A-E) with dots 3 and 6 added.

- The Fourth Decade (W and others): The letter W is a famous outlier as it was not common in the French alphabet of Braille’s time. Its pattern breaks the sequence, reflecting its later addition to the system. The remaining combinations are used for punctuation.

This logical structure wasn’t just aesthetic; it made the system incredibly efficient to learn and use. A numerical sign (dots 3, 4, 5, 6) placed before the letters A-J turns them into the digits 1-0. A capitalization sign (dot 6) precedes a letter to make it uppercase. Braille had created not just an alphabet, but a complete, extensible code for reading and writing.

Beyond the Alphabet: A True Writing System

Louis Braille’s system went even further, evolving to match the speed of thought and touch. This led to the development of different “grades” of Braille, much like how shorthand functions for sighted writers.

Grade 1 Braille is uncontracted, a direct letter-for-letter transcription. It’s perfect for beginners learning the alphabet. However, reading it can be slow, and the books are very bulky.

Grade 2 Braille, the universal standard for publications today, is a masterstroke of efficiency. It employs a system of contractions and abbreviations for common words and letter groups. For example, a single cell represents the word “and,” “for,” or “the.” Common suffixes like “-ing” or “-ed” also have their own single-cell representations. This dramatically increases reading and writing speed and significantly reduces the size of Braille books, making knowledge more portable and accessible.

This system of contractions is a sophisticated linguistic layer. It recognizes letter frequency and common patterns, optimizing the written form for the tactile medium, just as spoken languages evolve for phonetic efficiency.

From Paris to the Planet: The Fight for a Universal Standard

Despite its clear superiority, the adoption of Braille was not immediate. The sighted directors of the Paris institute were resistant, clinging to their embossed-letter traditions. For years, Braille’s system was an underground code, taught and used in secret by the students who knew its power.

Louis Braille died in 1852, just two years before his system was officially adopted by the French government. From there, its influence spread across the globe. The journey to a global standard wasn’t always smooth—in the English-speaking world, a “war of the dots” raged for decades between different competing tactile systems. But eventually, the logical supremacy of the six-dot cell won out, leading to the adoption of standards like Unified English Braille (UEB).

Today, Braille has been adapted for hundreds of languages, from Chinese and Arabic to Hebrew and Spanish. Its fundamental logic is so robust that it can elegantly represent different character sets, mathematical equations (Nemeth Code), and even complex musical notation. It is a testament to its design that a system created by a French teenager in the 1820s remains the undisputed global standard for non-visual literacy in the 21st century.

Braille is not a language in itself, but a writing system—a tactile code that unlocks any language. It is the invention that transformed blindness from a barrier to a characteristic. With six simple dots, Louis Braille didn’t just teach the blind to read; he gave them the tools for education, the means for employment, and the power of a voice written by their own hands.