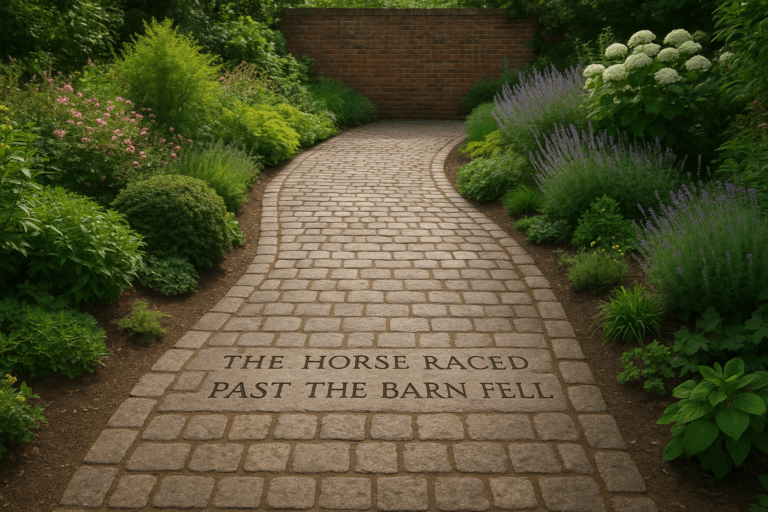

“The test came back positive.”

In almost any other context, these words are a cause for celebration. A positive attitude, a positive outcome, a positive review. But in the sterile quiet of a doctor’s office, “positive” can be one of the most terrifying words in the English language. It can mean the presence of disease, a marker for a frightening condition, or the confirmation of your deepest fears.

This single word is the perfect entry point into the doctor-patient language gap—a high-stakes communication chasm where shared words carry unshared meanings. This isn’t just about big, scary medical terms; it’s about the subtle, everyday language that can breed confusion, anxiety, and non-compliance. Welcome to the sociolinguistics of the medical consultation, where the wrong word choice can have consequences far beyond a simple misunderstanding.

The Jargon Wall: When “Unremarkable” is a Remarkable Relief

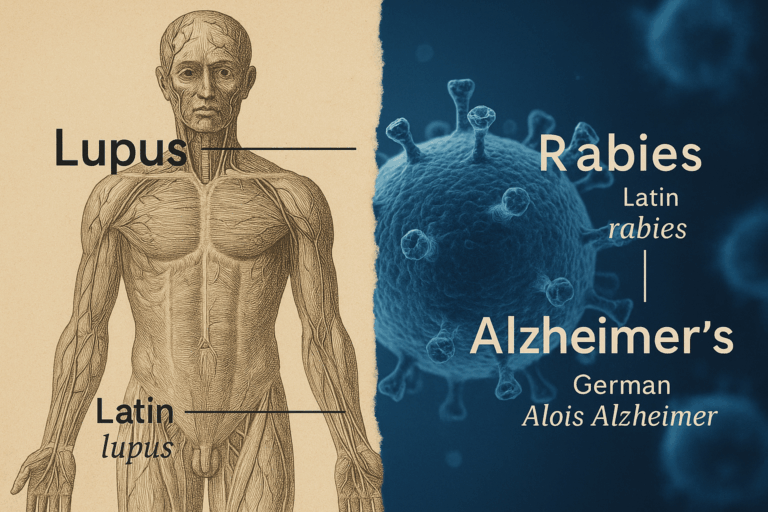

Every profession develops its own specialized vocabulary, a linguistic shorthand known as jargon. For medical professionals, this register is essential for communicating complex information with precision and speed to their colleagues. The problem arises when this same language is used, often unconsciously, with patients who are not part of that linguistic community.

The result is what we can call the “jargon wall,” an intimidating barrier built of unfamiliar terms. Consider these common examples:

- Positive vs. Negative: As we’ve seen, doctors use these terms to indicate the presence or absence of a specific biological marker they were testing for. For the patient, the words are irrevocably tied to their everyday connotations of “good” and “bad.”

- Acute vs. Chronic: A layperson hears “acute” and thinks “severe” or “intense.” In medicine, it simply means “of recent onset.” An “acute case of gastritis” sounds terrifying, but it just means your stomach lining suddenly became inflamed. “Chronic,” on the other hand, refers to duration (long-lasting), not necessarily severity.

- Unremarkable / Nonspecific: If a friend described your new haircut as “unremarkable,” you’d be offended. But when a radiologist reports that your MRI is “unremarkable,” it’s the best news you could possibly get. It means everything looks normal and healthy. Similarly, “nonspecific” findings mean there’s nothing that points to a specific, concerning disease.

- Idiopathic: This is a sophisticated-sounding word that simply means “of unknown cause.” While medically precise, to a patient it can sound evasive or even dismissive, as if the doctor is withholding information or has given up.

When a patient doesn’t understand these terms, they are left with two bad options: nod along and pretend to understand, leaving the office confused and scared, or interrupt and ask for clarification, which can feel intimidating or embarrassing.

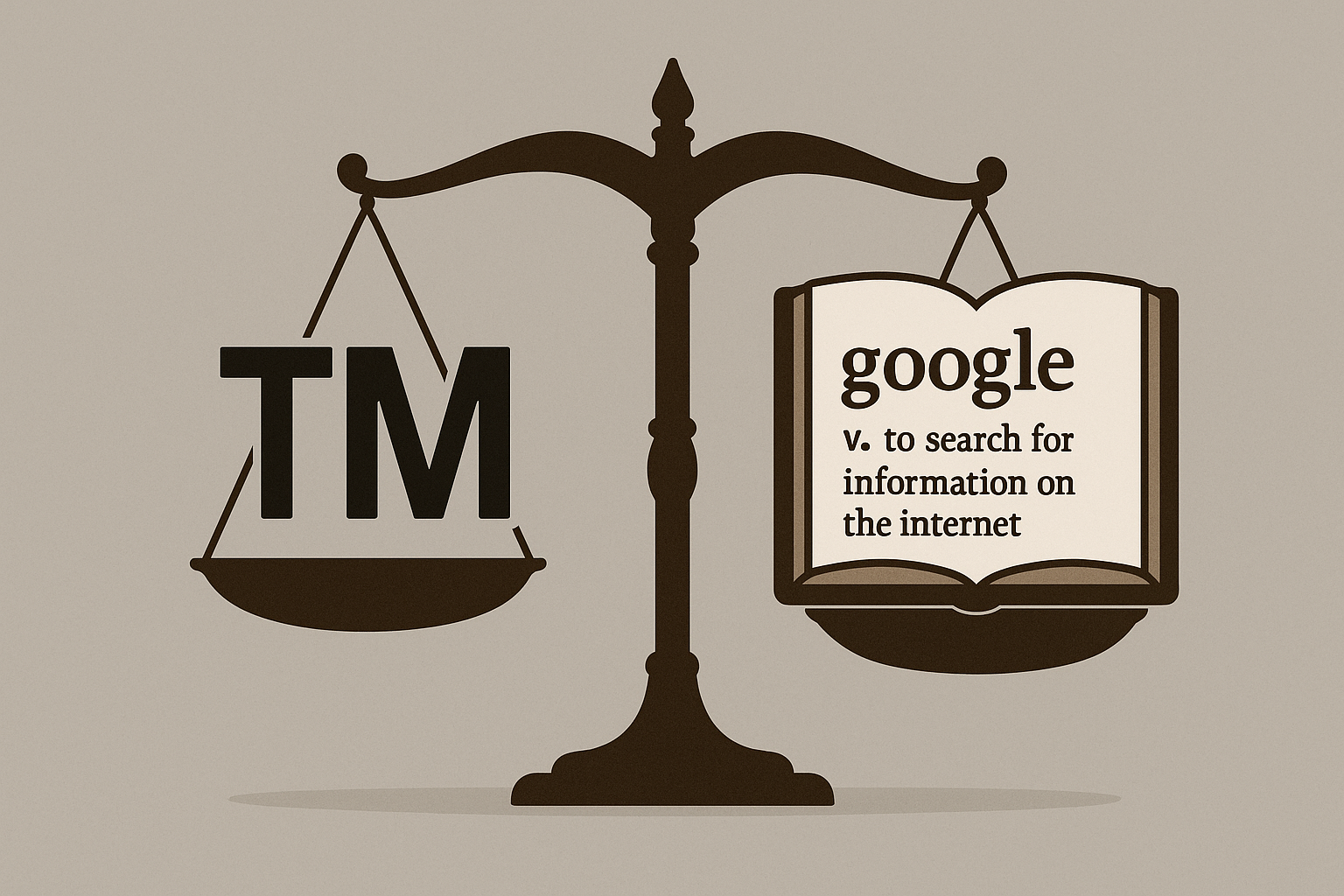

The Euphemism Treadmill: Softening the Blow or Obscuring the Truth?

If jargon is an accidental barrier, euphemism is often an intentional one. Doctors are human. They want to protect their patients from fear and distress. This noble intention leads to the use of softer, less direct language to deliver bad news. This is the “euphemism treadmill,” where language is softened to the point of becoming dangerously vague.

A doctor might talk about a “lesion,” a “mass,” or a “spot” on an x-ray, carefully avoiding the word “tumor” or the even more frightening “cancer.” They may describe a painful procedure as causing “some discomfort.” Instead of saying a treatment failed, they might say the patient “did not respond as we’d hoped.”

While this comes from a place of kindness, it can lead a patient to gravely underestimate the seriousness of their situation. The patient who is told “we found a small spot we need to keep an eye on” might not grasp the urgency of a follow-up appointment. The family who is told their loved one had an “adverse event” during surgery may not realize a critical error occurred. Clarity, even when it’s brutal, is often kinder than ambiguity.

Mismatched Models and Cultural Divides

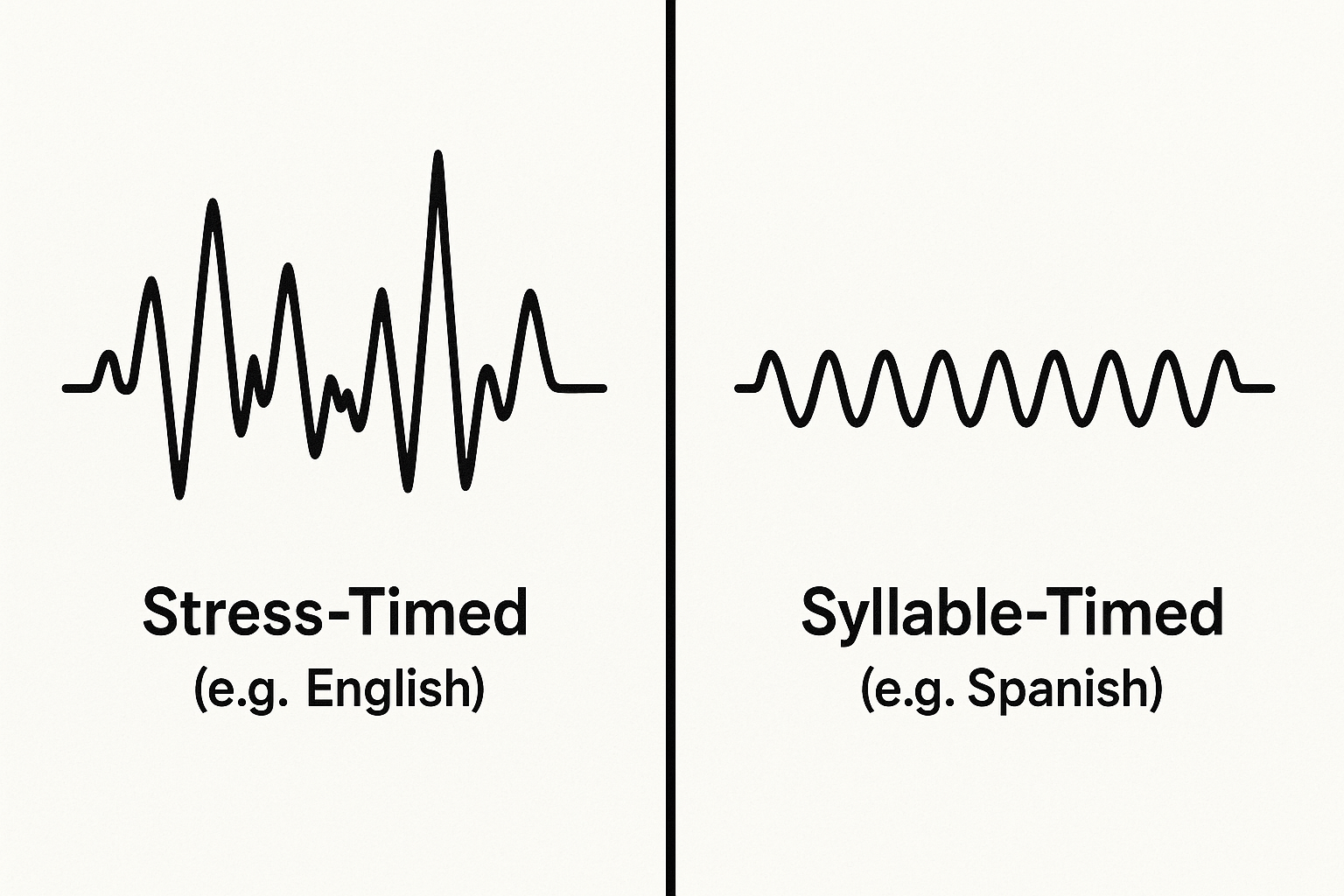

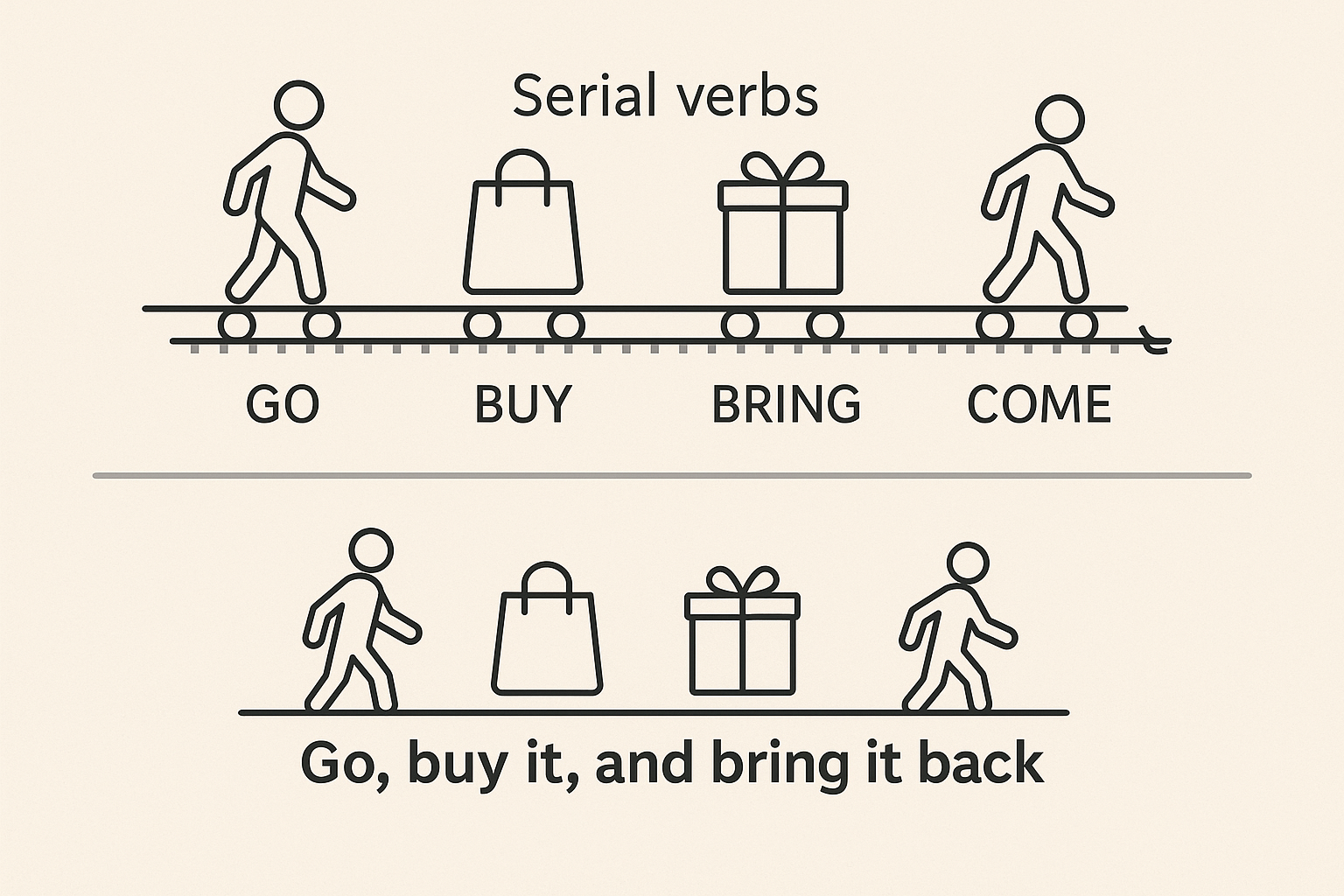

The language gap extends beyond individual words to the very structure of the conversation. Doctors are trained in the biomedical model. They are focused on pathophysiology, data, and biological systems—the disease. Patients, however, operate from a model of lived experience. They are concerned with symptoms, fear, and how their condition impacts their life, work, and family—the illness.

The doctor asks, “On a scale of 1 to 10, what is your pain level?” The patient wants to explain that the pain isn’t just a number; it’s the reason they can’t pick up their grandchild or sleep through the night. The doctor is collecting data; the patient is telling a story. When these two models don’t align, both parties can leave the interaction feeling frustrated and unheard.

Furthermore, cultural communication styles play a huge role. In some cultures, questioning a doctor—an authority figure—is seen as deeply disrespectful. Patients from these backgrounds may never ask for clarification, even when they are completely lost. Conversely, a doctor’s direct, matter-of-fact communication style, prized for its efficiency in some cultures, may be perceived as cold, uncaring, and rude in others that value indirectness and relational harmony.

Bridging the Gap: The Linguistics of Healing

Closing the doctor-patient language gap isn’t impossible. It requires a conscious effort from both sides to turn the medical monologue into a collaborative dialogue.

For healthcare providers, the solution is patient-centered communication:

- Avoid Jargon: Actively translate medical terms into plain language. Instead of “hypertension,” say “high blood pressure.” Instead of “neoplasm,” explain what a “growth” is and what it could mean.

- Use the Teach-Back Method: This is a simple, powerful tool. After explaining a concept, the provider asks, “To make sure I was clear, can you tell me in your own words what you need to do when you get home?” This isn’t a test of the patient’s knowledge, but a check on the clarity of the provider’s explanation.

- Embrace Analogy: A well-chosen metaphor can be incredibly illuminating. “Think of your artery as a garden hose that has a kink in it” is much more effective than describing “reduced luminal diameter.”

For patients, the key is empowerment:

- Ask Questions: You have the right to understand your health. It is always okay to say, “I’m sorry, I don’t understand that word,” or “Could you explain that in a different way?”

- Take Notes: Medical appointments can be overwhelming. Writing down key information, diagnoses, and instructions can help you process it later.

- Bring a Second Listener: A friend or family member can act as an advocate and another pair of ears, helping to catch details you might miss in the moment.

Ultimately, a medical consultation is one of the most important conversations a person can have. By recognizing that it is a linguistic event as much as a medical one, we can begin to dismantle the barriers that stand in the way of true understanding. Better communication doesn’t just reduce fear and confusion; it leads to better health outcomes and restores the human connection at the heart of healing.