“What will you do tomorrow?”

It’s a simple question, but the little word “will” is doing some heavy lifting. It acts as a grammatical time machine, instantly teleporting the conversation from the present to the future. For English speakers, this distinction is automatic, baked into the very structure of our language. But what if it wasn’t? What if your language treated tomorrow just like today?

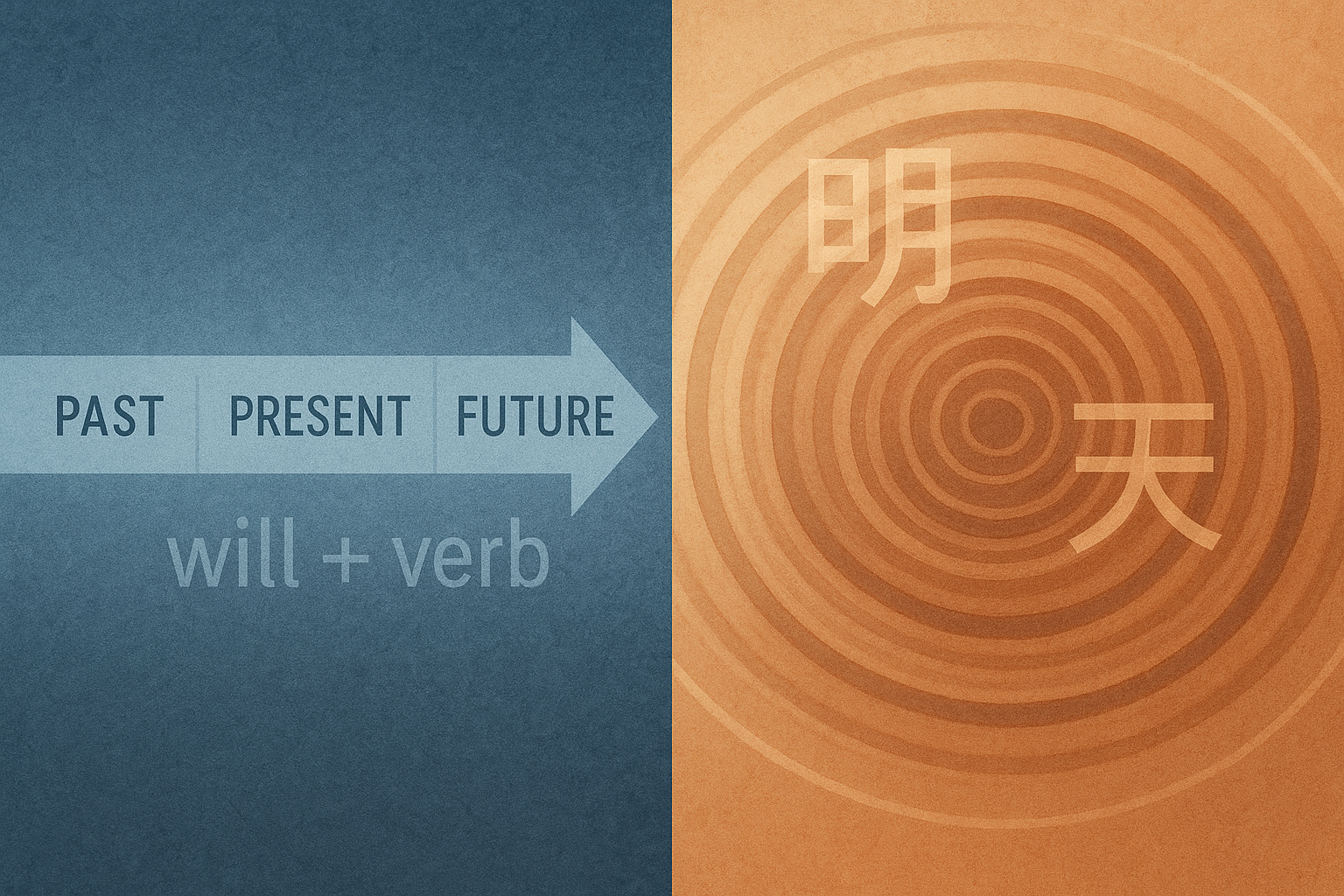

This isn’t a thought experiment. A vast number of the world’s languages, including giants like Mandarin Chinese and regional powerhouses like Finnish and German, lack a dedicated grammatical future tense. They don’t have a direct equivalent of “will” or “shall.” This fascinating linguistic feature raises a profound question: if your language doesn’t grammatically fence off the future, does it change how you think about it, plan for it, and live in it?

What Does “No Future Tense” Actually Mean?

First, let’s clear up a common misconception. Speakers of these languages can, of course, talk about the future. The sky doesn’t fall if a Finn wants to make plans for next week. The difference is not in what they can express, but how they express it.

Instead of conjugating a verb into a future form, these languages—which linguists sometimes call “futureless” languages—rely on other clues. The most common tools are context and temporal adverbs.

Consider the difference:

- English (Futured Language): “I will go to the store tomorrow.” The verb phrase “will go” clearly marks the action as futuristic.

- Mandarin Chinese (Futureless Language): 我明天去商店 (wǒ míngtiān qù shāngdiàn). This translates literally to: “I tomorrow go store.” The verb 去 (qù, “to go”) is the same whether the action is happening now or tomorrow. The word 明天 (míngtiān, “tomorrow”) does all the work.

- Finnish (Futureless Language): “Menen huomenna kauppaan.” This translates to: “I go tomorrow to the store.” The verb “menen” is in the present tense. Again, “huomenna” (“tomorrow”) signals the future time frame.

In these languages, the future is treated as a continuation of the present, simply shifted by an adverb. For speakers of “futured” languages like English, French, and Spanish, the future is a distinct grammatical territory that requires a special passport to enter.

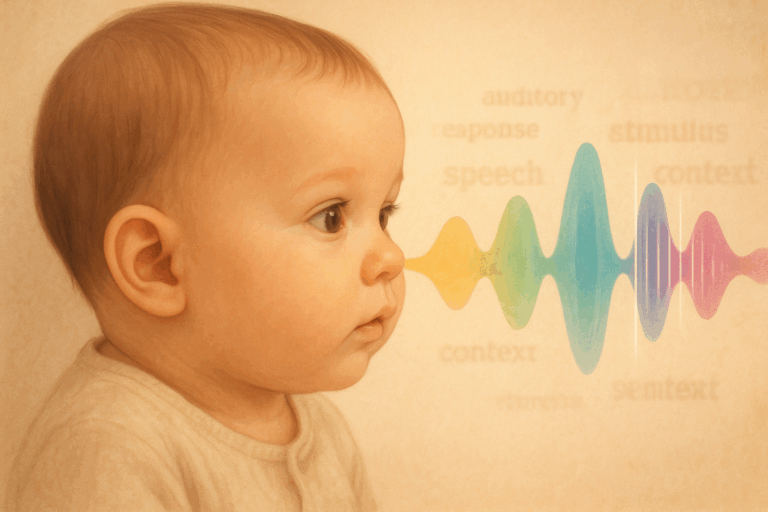

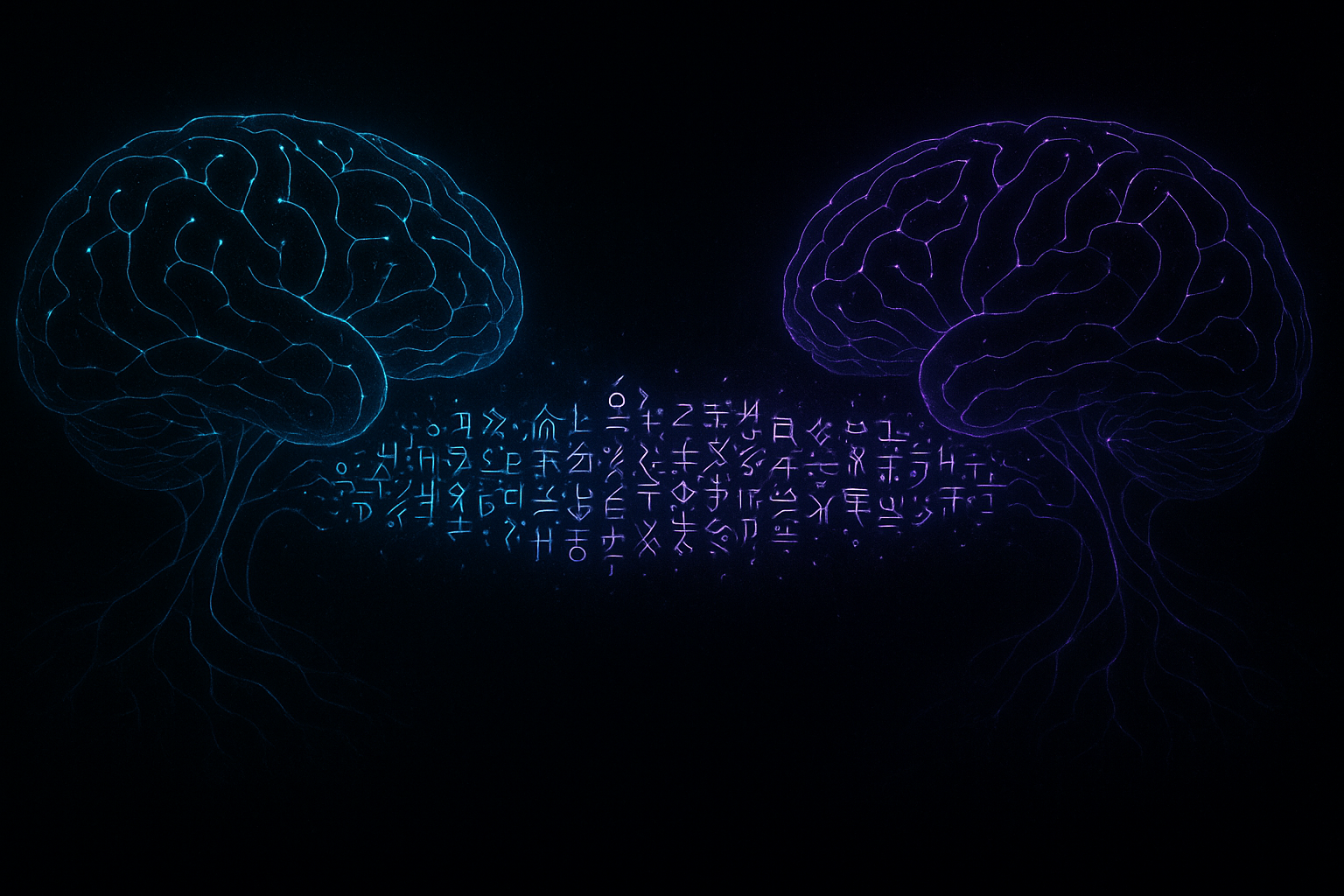

Linguistic Relativity and the Perception of Time

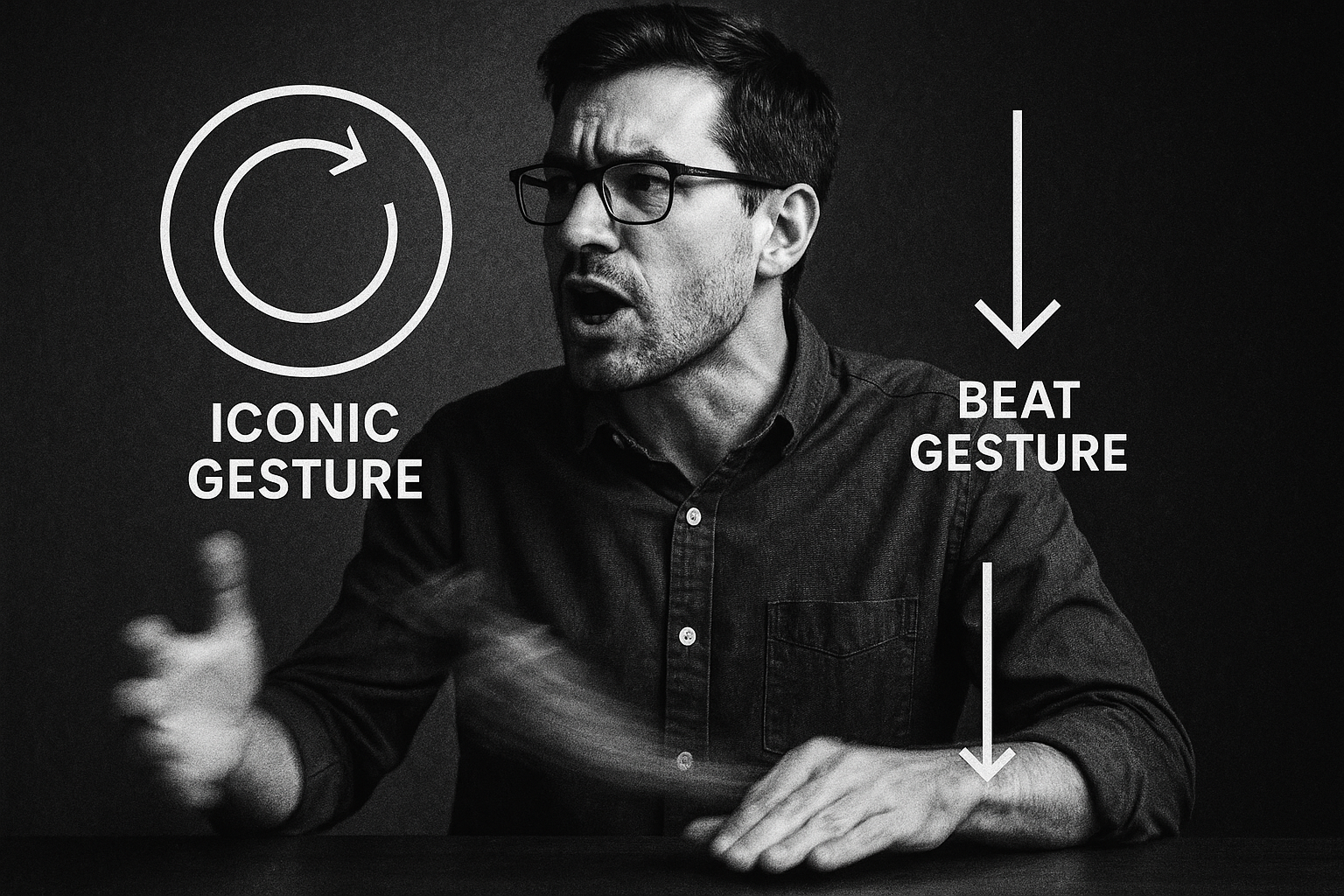

This grammatical divide is where things get really interesting. The idea that language can influence thought, known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis or linguistic relativity, suggests that the structures of our language can shape our perception of reality.

In 2013, behavioral economist Keith Chen at UCLA published a controversial but captivating paper exploring this very idea. Chen proposed that languages that grammatically separate the present and future (futured languages) lead their speakers to subconsciously perceive the future as a more distant, distinct entity. If the future is “another place,” it becomes easier to put off preparing for it. It feels less connected to the “me” of today.

In contrast, speakers of futureless languages, by discussing the present and future with the same grammatical toolkit, are led to perceive the future as an immediate extension of the present. The “me” of tomorrow is not a stranger; they are just “me,” tomorrow.

The Economic Connection: Saving, Health, and Planning

Chen took this hypothesis and tested it against massive global datasets of economic and social behavior. The correlations he found were startling. After controlling for a wide range of factors like GDP, demographics, and cultural history, he discovered that speakers of futureless languages consistently demonstrated more future-oriented behavior.

Compared to speakers of futured languages, they were:

- 30% more likely to save money in any given year.

- Likely to have accumulated 25% more in retirement savings.

- Less likely to smoke and more likely to exercise regularly.

- More likely to practice safe sex.

The logic is compelling. If your language makes “saving money next year” sound grammatically identical to “saving money now,” the psychological barrier to saving is lower. The future pain of poverty feels more immediate, and the immediate pain of forgoing a purchase feels more manageable because the future reward is conceptually closer. It’s the difference between planning for a storm that will happen and one that is happening tomorrow.

A World of Caveats and Counterarguments

As compelling as Chen’s theory is, it’s essential to approach it with a healthy dose of skepticism. The world of linguistics and economics is rarely so simple. Critics were quick to point out several crucial caveats.

The most significant challenge is the age-old maxim: correlation does not equal causation. While the link is there, it’s incredibly difficult to prove that the language causes the behavior. Other powerful forces are at play. For example, many of the futureless-language countries in Chen’s study are in Northern Europe (Germany, the Netherlands, Finland), where cultural values around thrift and planning are already strong. Is it the language, or is it a shared cultural heritage that just happens to coincide with a linguistic feature?

Furthermore, the classification of languages as “futured” or “futureless” can be an oversimplification. German, for instance, has a formal future tense using the verb werden (e.g., “Ich werde gehen” – “I will go”). However, in everyday speech, Germans overwhelmingly prefer using the present tense with an adverb (“Ich gehe morgen” – “I go tomorrow”), making it function like a futureless language. This nuance complicates a clean-cut division.

Beyond Economics: A Philosophical Shift

Putting aside the economic debate, the concept invites us to consider the philosophical implications. If language shapes reality, how does a futureless structure mold the very concept of time?

Perhaps for speakers of these languages, time is not a series of discrete boxes—Past, Present, Future—but a continuous, flowing river. The future isn’t a foreign country you plan to visit one day; it’s simply the part of the river that’s around the next bend. This perspective could foster a worldview grounded in continuity, where present actions and future consequences are inextricably linked in a seamless tapestry.

This isn’t to say one view is better than another, only that they are different. The grammatical scaffolding of our native tongue may provide us with a default way of seeing the world, a lens we rarely notice we’re looking through.

So, the next time you talk about your plans, pay attention to those small words. When you say “I will,” you are performing a subtle but powerful act of cognitive separation. And it’s worth wondering: how might your plans, your savings, and your very perception of tomorrow change if you simply said, “Tomorrow, I do”?