If you’ve ever tried to learn French, you’ve likely stared at a word like beaucoup (a lot) or oiseaux (birds) and asked the universe: “Why are all these letters here if I’m not supposed to say them?” It’s a classic frustration. The French writing system seems littered with letters that have apparently given up their day job. They sit there on the page, silent and mysterious.

But what if these letters aren’t silent at all? What if they’re more like ghosts, invisible to the ear but exerting a powerful influence on the world of the living—or in this case, the pronounced? This is the secret of French orthography. These silent letters are not bugs; they are features. They are crucial phonetic and grammatical markers that shape the sound, flow, and structure of the language in profound ways.

The Phantom of the Syllable: The Mighty “E Muet”

At the heart of this spectral system is the most famous ghost of all: the e muet, or “mute e.” Also known as the e caduc (“falling e”), this letter is the unsung hero of French pronunciation. While it’s often unvoiced, its presence—or absence—is anything but insignificant. It performs at least three critical jobs.

Job #1: It Softens the Preceding Consonant

In French, the letters ‘c’ and ‘g’ can have a hard or a soft sound, depending on the vowel that follows them. A, O, and U trigger the hard sounds (/k/ and /g/), while E and I trigger the soft sounds (/s/ and /ʒ/, like the ‘s’ in “measure”).

The silent ‘e’ is the key to forcing a soft sound at the end of a word or before a “hard” vowel. Consider the verb manger (to eat). In the nous form, we need to add the “-ons” ending. If we just wrote “mangons,” the ‘g’ would be followed by an ‘o’, forcing a hard /g/ sound (“man-gons”). To preserve the soft /ʒ/ sound of the root verb, French orthography inserts a silent ‘e’: nous mangeons (noo mahn-zhong). That ‘e’ is completely silent, yet it protects the sound of the ‘g’. It’s a phonetic shield.

Job #2: It Wakes Up the Final Consonant

This is perhaps the e muet‘s most dramatic role. Many French consonants are silent at the end of a word. But add a final ‘e’—often to mark the feminine form of an adjective or noun—and that sleeping consonant suddenly springs to life.

Observe this magic in action:

- The masculine adjective for “small” is petit. The final ‘t’ is silent: /pə.ti/.

- The feminine form is petite. The ‘e’ is silent, but its presence forces you to pronounce the ‘t’: /pə.tit/.

This pattern is everywhere:

- grand /ɡʁɑ̃/ vs. grande /ɡʁɑ̃d/ (big)

- vert /vɛʁ/ vs. verte /vɛʁt/ (green)

- français /fʁɑ̃.sɛ/ vs. française /fʁɑ̃.sɛz/ (French)

The silent ‘e’ acts as a trigger, a signal to the reader that the preceding consonant is no longer off-duty. It’s a grammatical marker with a direct phonetic consequence.

Job #3: It Upholds the Rhythm of the Language

French is a syllable-timed language, which contributes to its musical, flowing quality. The e muet plays a vital role here, acting as a potential syllable that can be included or dropped to maintain the rhythm.

In everyday, casual speech, the e muet is almost always dropped. For example, samedi (Saturday) is pronounced “sam-di.” But in more formal speech, poetry, or song, it can be pronounced to add a syllable and avoid awkward consonant clusters. The famous line from the French national anthem, “Le jour de gloire est arrivé,” is sung with a distinct ‘e’ in “gloire” (glwa-ruh) to fit the musical meter.

Similarly, a phrase like notre dame is much easier to pronounce as two smooth syllables (/nɔ.tʁə/) than one crunchy one (/nɔtʁ/). The e muet in notre acts as a buffer, ensuring the language flows without tripping over its own consonants.

Beyond the ‘E’: The Company of Consonant Ghosts

The e muet may be the star, but it’s not the only ghost on the French stage. The legions of silent final consonants (-s, -t, -d, -p, -x, -z) also have hidden jobs, primarily related to grammar and the elegant phonetic dance known as liaison.

Grammatical Clues in Plain Sight

Think about plurals. In English, we hear the difference between “cat” and “cats.” In French, le chat (the cat) and les chats (the cats) sound identical in isolation. The silent ‘-s’ is a purely visual grammatical marker. The same is true for many verb conjugations. Il parle (he speaks) and ils parlent (they speak) are pronounced exactly the same. The silent “-ent” ending is an essential clue for the reader, even if the listener doesn’t hear it.

This might seem inefficient, but it preserves a visual distinction that clarifies meaning, much like the difference between “their,” “there,” and “they’re” in English.

The Art of the Liaison: When Ghosts Speak

Here is where the consonant ghosts truly reveal their purpose. A liaison is the phonetic linking of a word’s normally silent final consonant to the opening vowel sound of the following word. Suddenly, the ghost is no longer a ghost—it’s fully voiced.

This is how silent letters create the seamless, connected sound of spoken French.

les + amis → “les amis” is pronounced /le.za.mi/ (lay-zah-mee)

nous + avons → “nous avons” is pronounced /nu.za.vɔ̃/ (noo-zah-vohn)

un grand + arbre → “un grand arbre” is pronounced /œ̃ ɡʁɑ̃.taʁbʁ/ (un grahn-tarbr)*

*Note: The ‘d’ in grand is pronounced as a ‘t’ in this liaison.

These consonants weren’t really silent; they were just waiting for the right moment. They exist on the page to be activated under specific phonetic conditions. This system allows words to flow together beautifully, eliminating the choppy gaps that would otherwise occur between a word ending in a consonant and one beginning with a vowel.

A Whisper From History

Why did French end up this way? The answer lies in its evolution from Vulgar Latin. The French language went through a period of profound sound change where final consonants and unstressed syllables were gradually dropped from pronunciation. However, the spelling system remained far more conservative.

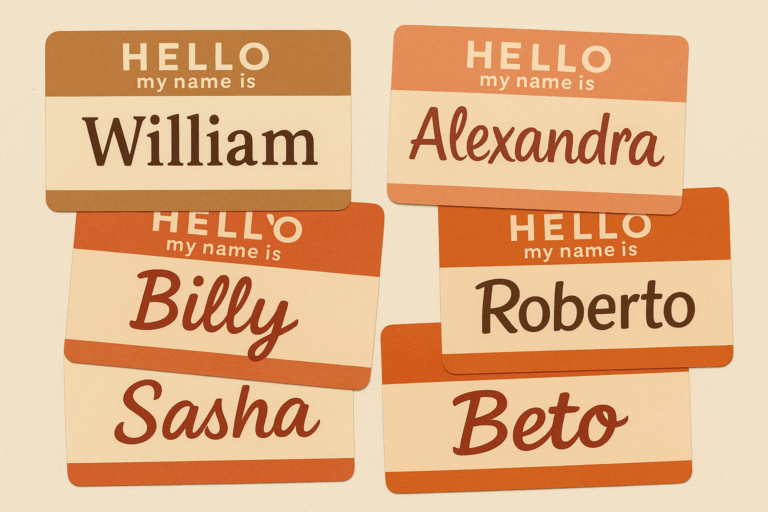

Scribes and later the influential Académie française (which has governed the French language since 1635) chose to retain many of these letters. The reasons were varied: to preserve the etymological link to Latin, to distinguish between homophones (e.g., ver [worm], vert [green], vers [towards], and verre [glass]), and to encode the grammatical and phonetic rules we’ve just explored.

Embracing the Ghosts

For the French learner, these silent letters can feel like a pointless obstacle course. But once you understand their function, a new appreciation emerges. They are not random artifacts but a sophisticated, if complex, system of signals.

They tell you how to pronounce a consonant, when to add a syllable, and where to connect words into a seamless flow. They are the ghosts in the machine of the French language—unseen, unheard, but shaping everything. So the next time you see a word overflowing with silent letters, don’t despair. Instead, listen closely for the whispers of its ghosts; they’re telling you exactly how to speak.