A Child in the Attic, A Question for Science

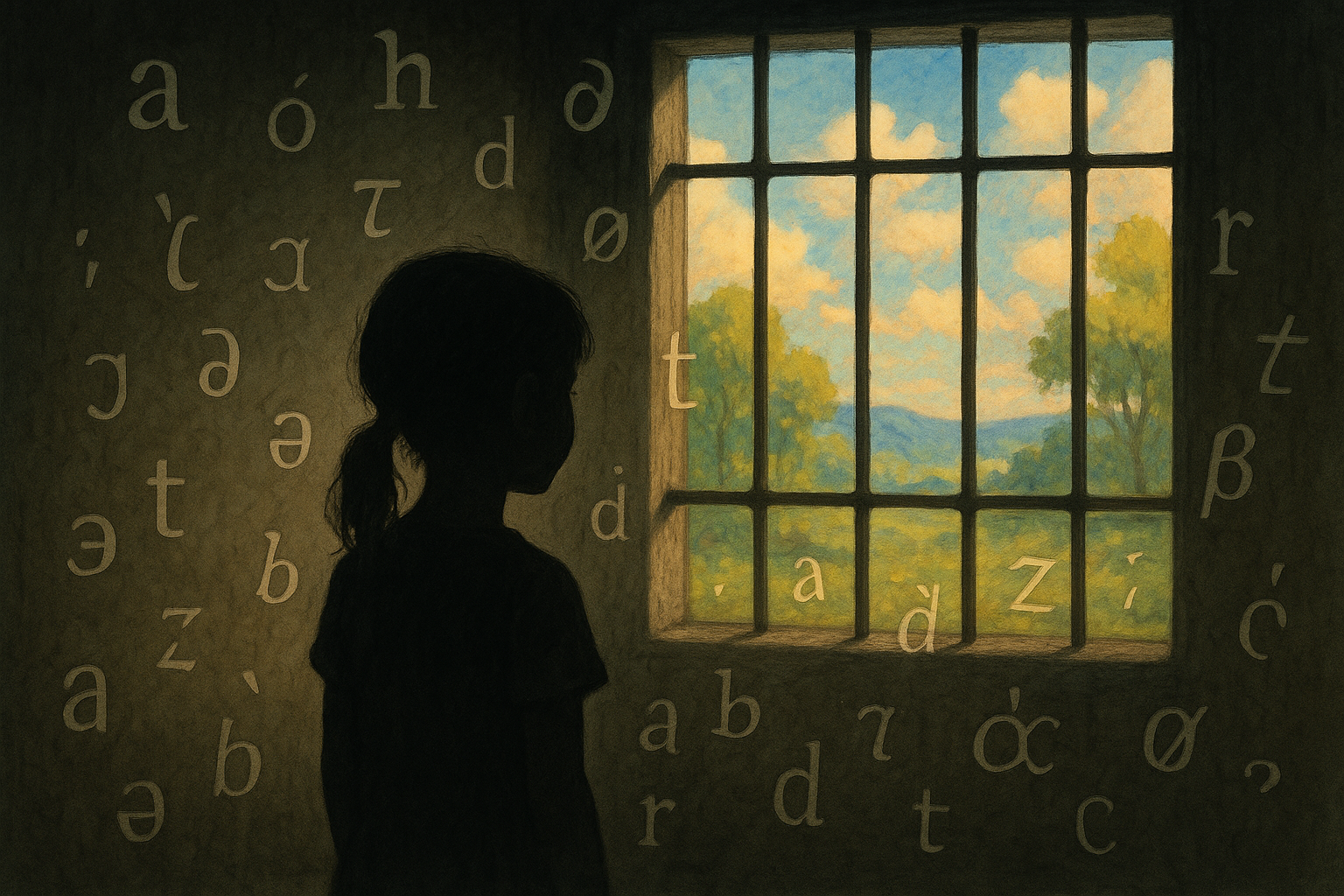

In November 1970, a social worker in a quiet Los Angeles suburb stumbled upon one of the most shocking cases of child abuse in modern history. Following up on a case, she discovered a 13-year-old girl who weighed only 59 pounds and stood just 54 inches tall. The child couldn’t straighten her arms or legs, couldn’t chew solid food, and couldn’t speak. She made no sounds at all. She had spent more than a decade of her life in near-total isolation, often strapped to a potty chair in a silent, darkened room. This child, known to the world by the pseudonym “Genie,” had been deprived of nearly all human contact and, crucially, language.

Her discovery was a human tragedy, but for scientists, it presented a harrowing and unprecedented opportunity. Genie was a real-life “feral child,” a human raised outside the bounds of society. Her case became a living experiment, forcing linguists, psychologists, and neuroscientists to confront a fundamental question: Is there a point of no return for learning to speak? Genie’s struggle would become the most powerful—and ethically fraught—test of a crucial theory in linguistics: the critical period hypothesis.

The Critical Period: A Biological Clock for Language

The critical period hypothesis, most famously articulated by linguist and neurologist Eric Lenneberg in 1967, proposes that the human brain is biologically primed to acquire language, but only for a limited time. This “window of opportunity” is thought to open in infancy and close sometime around puberty. During this period, a child’s brain is remarkably plastic, able to absorb the complex rules of grammar and sound with seemingly little effort. After this window closes, the theory goes, the brain’s ability to build the fundamental architecture for language is severely diminished, if not lost entirely.

Think of it like this:

- Learning a first language as a child: It’s like growing a limb. It happens naturally, organically, as part of your biological development, given the right “nutrients” (i.e., exposure to speech).

- Learning a second language as an adult: It’s more like building a prosthetic limb. You can make it functional, even excellent, but it requires conscious effort, study, and it may never feel as natural or be as perfectly integrated as the original.

Before Genie, the evidence for this hypothesis was indirect—gleaned from second-language learners or studies of deaf children who were not exposed to sign language early on. Genie, having had virtually no linguistic input during this entire critical period, was a unique, tragic test case. Could she learn to talk now that she was free?

Words Without Grammar

After being rescued, Genie became the focus of an intensive, multidisciplinary study. A team of researchers, led by psychologist David Rigler and including linguist Susan Curtiss, worked tirelessly to rehabilitate her and, in the process, document her development. Initially, the progress was astounding.

Genie was curious, intelligent, and desperate to communicate. She quickly began to learn words. She learned the names of colors, objects, and people in her new life. Within months, she had a significant vocabulary and could express her needs and feelings. She could point to a picture and say “blue” or “mother.” She loved music and would spell out words she heard on the radio with her fingers. This lexical explosion showed that the ability to learn and store words is not strictly limited by age.

But as the months turned into years, a crucial piece of the linguistic puzzle remained missing: grammar.

While she could string words together, her speech remained telegraphic and unstructured. She never mastered the rules of syntax that govern how words are combined to form meaningful sentences. For example, she might say:

- “Applesauce buy store.”

- “Mike paint.”

- “I like hear music.”

Her speech lacked function words (like ‘a’, ‘the’, ‘in’), grammatical morphemes (the ‘-s’ for plurals or ‘-ed’ for past tense), and the ability to form complex questions or negative sentences correctly. She could convey a message, but she couldn’t wield the intricate machinery of grammar that children typically master by age five. It was as if she had a box full of beautiful Lego bricks (words) but no instructions on how to build a castle (a sentence).

What Genie’s Struggle Revealed

Genie’s lopsided development provided powerful, if heartbreaking, evidence for the critical period hypothesis. Her case suggested a profound distinction between different components of language:

- Lexical Learning (Vocabulary): The ability to learn words seems to be a resilient skill that can be developed throughout life.

- Grammatical Learning (Syntax): The ability to unconsciously acquire the complex rule system of a language appears to be highly dependent on exposure during the critical window of childhood.

Neurological tests added another layer to the story. In most right-handed people, language is heavily processed in the brain’s left hemisphere. Scans of Genie’s brain, however, showed that she was processing language primarily in her right hemisphere. One theory is that without stimulation during the critical period, the language centers in her left hemisphere had “atrophied” or failed to develop, and her brain was trying to compensate by using the less-specialized right hemisphere. This could explain her difficulty with the logical, rule-based system of grammar.

An Ethical Quagmire and a Tragic End

Genie’s story is not just a scientific case study; it’s a cautionary tale. The line between therapy and research became dangerously blurred. After four years, the National Institute of Mental Health, which funded the project, cut its funding amid concerns that the research had become disorganized and was prioritizing scientific inquiry over Genie’s own well-being. A bitter custody battle ensued, and Genie was moved from the care of the research team.

Tragically, her life after the project was a series of placements in abusive and neglectful foster homes. In one, she was severely punished for vomiting and, as a result, retreated back into the silence from which she had so bravely emerged. She stopped speaking almost entirely. Today, Genie lives in an adult care facility in California. Her location is private, a final, small protection for a life marked by unimaginable exploitation and suffering.

Her case leaves us with a profound lesson. Language is more than a tool for communication; it is a biological birthright that requires nurturing to flourish. The tragic silence that defined Genie’s childhood and returned in her adulthood underscores that the intricate dance between our biology and our environment is what makes us fully human. Her story is a testament to the tragic limits of our own development and a stark reminder that some windows, once closed, may never be opened again.