This is the grammar of nicknames—the fascinating, unwritten rules of morphology (word structure) and phonology (sound systems) that govern how we show affection and familiarity. Linguists call these forms hypocoristics, and they are a universal feature of human language, a testament to our social nature.

The English Nickname Factory: Clipping, Suffixes, and Strange Rhymes

English has a few reliable tools in its nickname-creation workshop. The most common processes involve shortening names and adding a familiar suffix.

The Art of the Clip

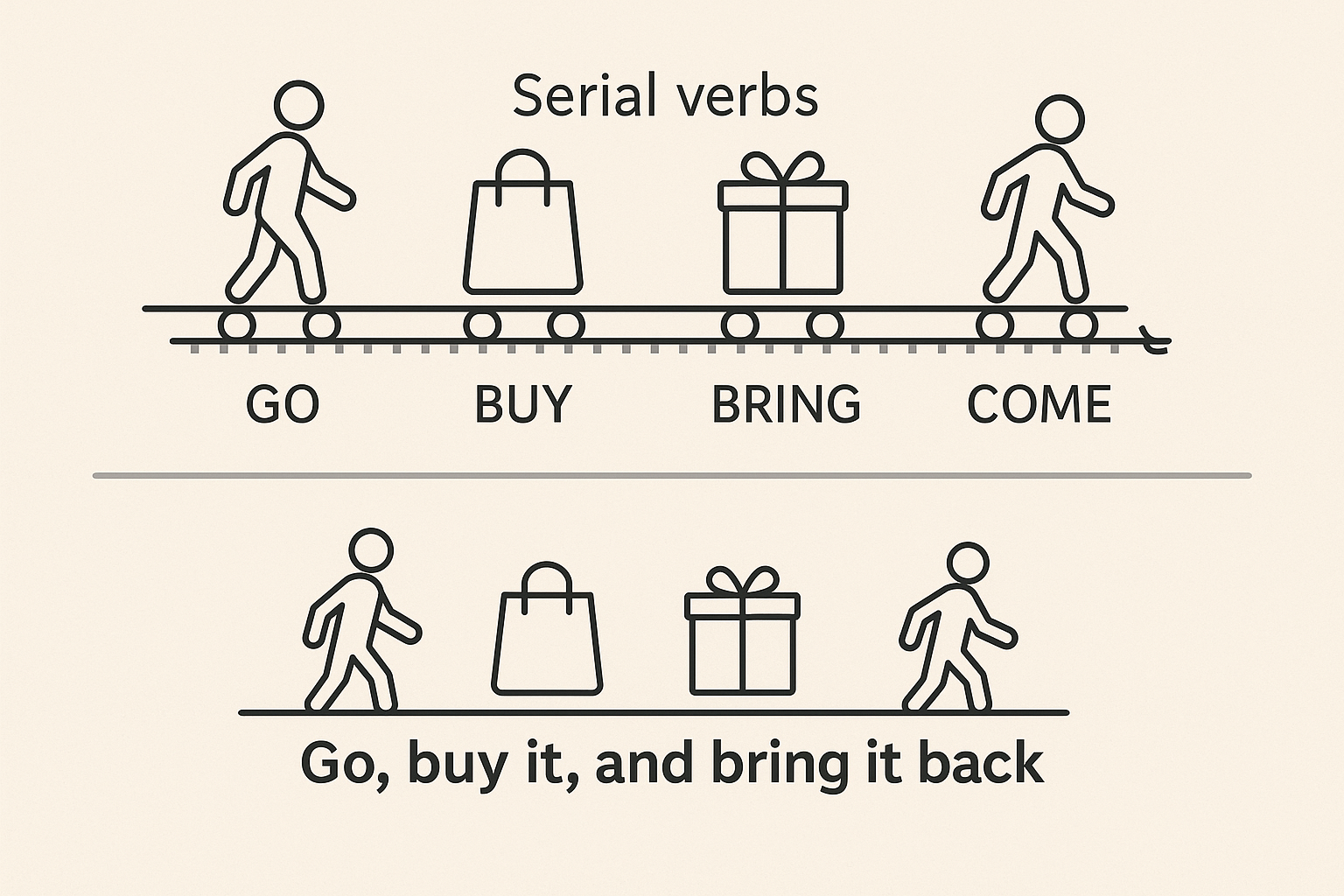

The simplest way to create a nickname is by clipping, or shortening, a longer name. This usually happens in one of two ways:

- Back-clipping: The end of the name is dropped. This is the most common form in English. (William → Will, Cynthia → Cynth, Robert → Rob)

- Fore-clipping: The beginning of the name is dropped. This is less common but still prevalent. (Elizabeth → Beth, (Al)fredo → Fredo)

The “rule” here is phonological: we tend to clip the name down to its first, most stressed syllable. For Re-BEC-ca, the stressed syllable is the second one, which is why she becomes Becca, not Reb.

Just Add “-y”: The Diminutive Suffix

Once you have your clipped, single-syllable name, the next step is often to add the quintessential English diminutive suffix: -y or -ie. This suffix carries a powerful social meaning, transforming a simple shortening into a term of endearment, informality, or even childishness.

Think about the difference between Sue and Susie, or Bill and Billy. The “-y” version feels warmer, closer, and more personal. This suffix almost always attaches to a clipped, stressed syllable:

- Susan → Sue → Susie

- Robert → Rob → Robby

- Patricia → Pat → Patty

The Curious Case of Rhyming Slang

Then we have the head-scratchers. How does Richard become Dick? Or William become Bill? This isn’t random; it’s a relic of linguistic history, particularly from Middle English.

Centuries ago, rhyming was a popular way to create name variations. The process went something like this:

- Richard → Rick (clipping) → Dick (rhyming substitution)

- Robert → Rob (clipping) → Bob (consonant swap)

- William → Will (clipping) → Bill (consonant swap)

- Margaret → Meg (clipping) → Peg (consonant swap)

These forms stuck around, becoming so conventional that today we don’t even think of them as rhyming slang. They’re just part of the established “grammar” of English nicknames.

A Nickname Tour of the World

These principles of shortening and adding affectionate suffixes are not unique to English. Let’s take a look at how other languages put their own spin on the grammar of familiarity.

Russian: The Suffix Buffet

Slavic languages, and Russian in particular, have an incredibly rich and nuanced system of diminutives. A single name can have half a dozen variations, each signaling a slightly different level of affection or context. Take Aleksandr:

- The Standard Short Form: Sasha. This common form uses the -sha suffix. Similarly, Maria becomes Masha.

- The Affectionate Diminutive: Sashenka. The -enka suffix adds a layer of tenderness, something a mother might call her child.

- The Cutesy/Childish Form: Sashechka. The -echka suffix is even more endearing and intimate.

Choosing the right form is a complex social dance. Using Sashechka with a work colleague would be bizarre, but using Aleksandr with your own child might sound cold and distant.

Spanish: The World of -ito and -ita

Anyone who has studied Spanish is familiar with the beloved diminutive suffixes -ito (masculine) and -ita (feminine). While they literally mean “little,” their primary function in names is to express affection.

- Juan → Juanito

- Ana → Anita

- Carlos → Carlitos

This pattern is beautifully productive in Spanish, extending far beyond names to almost any noun. A perro (dog) becomes a lovable perrito (doggie), and your abuela (grandmother) becomes your dear abuelita.

Japanese: Honorifics as Intimacy Markers

Japanese takes a different approach. Instead of changing the name itself, intimacy is often shown by attaching an honorific suffix. While not a diminutive in the morphological sense, these suffixes serve the same social function.

- -chan: The ultimate term of endearment. It’s used for children, close female friends, family members, and even pets. If your friend is named Yuki, calling her Yuki-chan signals closeness and affection.

- -kun: Typically used for boys or for men who are junior in age or status. It’s less intimate than -chan but more familiar than the standard, all-purpose -san.

Why Do We Bother? The Social Heart of Nicknames

So why is this a human universal? Why do we expend so much linguistic energy creating these alternative names? The answer lies in our fundamental need for connection.

Nicknames are powerful social tools. They:

- Create In-Groups: Using a nickname is a way of saying, “You and I are in a special club.” The outside world may know him as Jonathan, but to us, he’s Johnny. It builds a boundary of shared experience and intimacy.

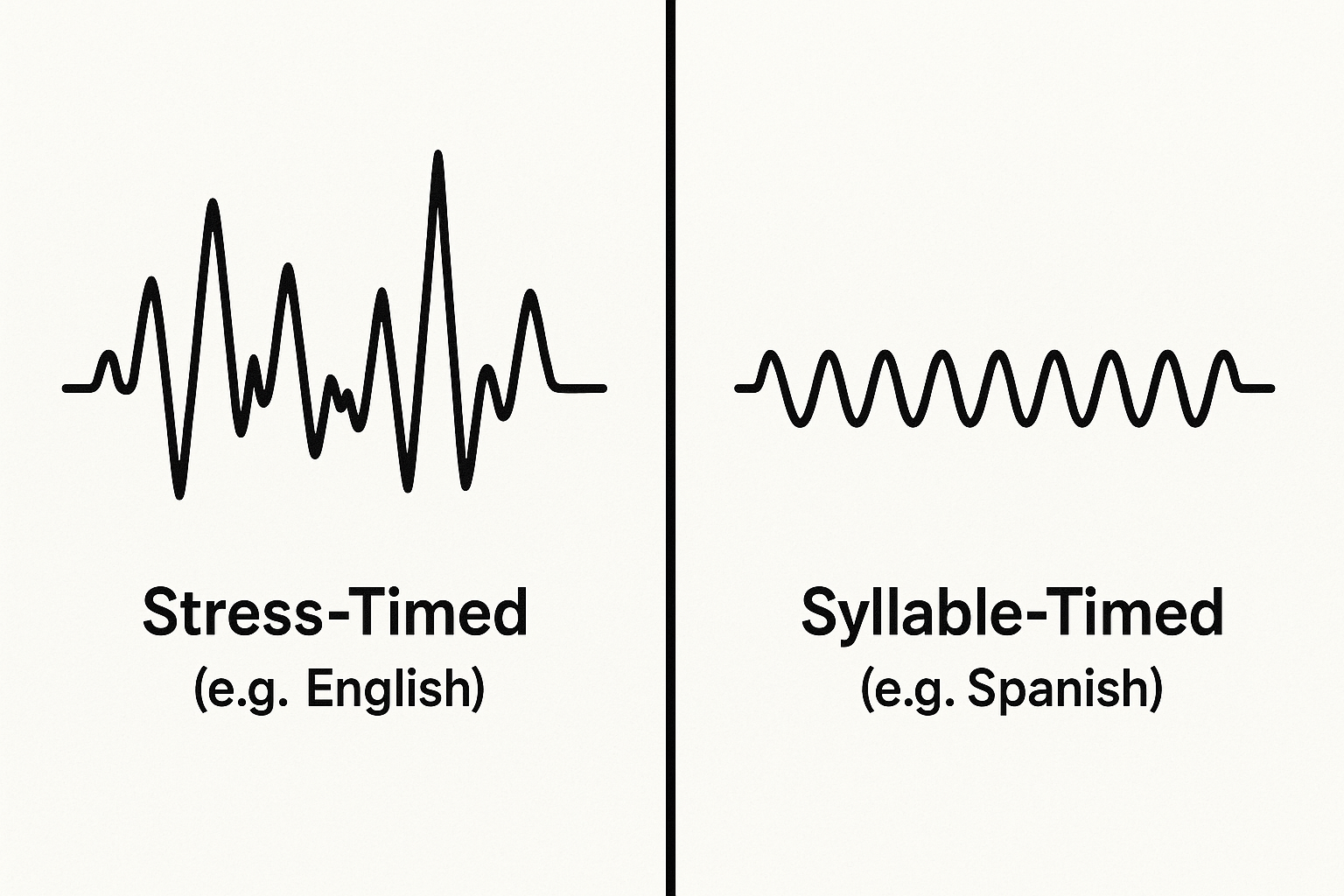

- Signal Affection: The sounds themselves often contribute to the feeling. Many diminutive suffixes, like the English “-y” and Spanish “-ito,” use high, front vowels (like the “ee” sound), which phoneticians have linked to perceptions of smallness and pleasantness across languages—a concept known as sound symbolism.

- Shape Identity: A nickname can be a way to present a different side of oneself. A “Robert” might be a formal professional, while “Bob” is the guy you watch football with. Nicknames allow us to have different personas for different parts of our lives.

The grammar of nicknames is a beautiful example of how language is more than just a tool for conveying information; it’s a system for building and maintaining relationships. The next time you call a friend by their nickname, take a moment to appreciate the complex, unwritten rules you’re following—a secret, shared grammar of the heart.