The short answer is: we all do. And no one does.

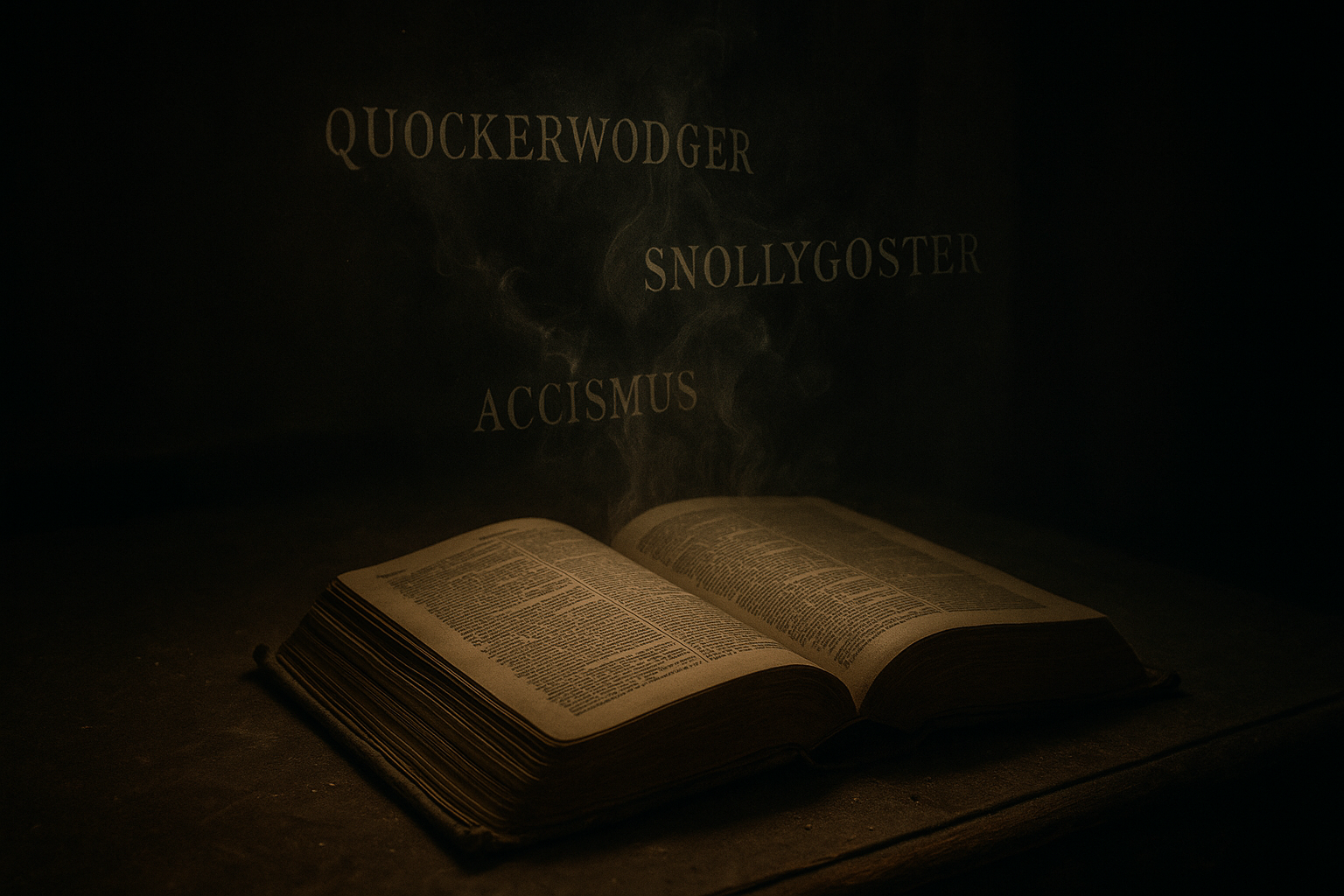

Unlike a formal ceremony, a word’s demise is a slow, organic process of collective neglect. There is no single authority, no linguistic coroner who signs a death certificate. Instead, a word’s journey into obsolescence is a story told through data, cultural shifts, and the simple act of being forgotten.

The Natural Life Cycle of a Word

To understand word death, we must first appreciate word life. Words are not static; they are born, they mature, they evolve, and sometimes, they die. A word might be born as a neologism (a newly coined term), borrowed from another language, or created by blending two existing words (like smog from smoke and fog).

For a while, it thrives. It finds its niche, people use it, and it communicates a clear and useful idea. But then, things can change. The world it described may vanish, a more fashionable synonym might push it aside, or its meaning might drift so far from its origin that it effectively becomes a new word entirely. This is the path to the graveyard.

An Autopsy: The Causes of Word Death

Words don’t die of old age; they die of irrelevance. The reasons for their decline are deeply intertwined with human progress and changing social landscapes.

- Technological Obsolescence: This is the most straightforward cause. When a technology disappears, the words associated with it become relics. Consider the vocabulary of a mid-20th-century office: rolodex, mimeograph, switchboard. Younger generations may have a vague understanding of these terms from old movies, but they have zero practical use for them. Words like wainwright (a wagon-maker) or fletcher (an arrow-maker) died when their professions were rendered obsolete by new technology.

- Cultural Shifts: Society changes, and so do the words we use to describe it. The term charwoman, for a cleaning lady, feels deeply archaic. The word spinster, once a neutral term for a woman who spins thread, became a pejorative for an unmarried woman and is now largely avoided for its negative connotations. As our social norms and values evolve, the language we use to express them must also adapt, leaving older terms behind.

- Semantic Replacement: Sometimes, a word is simply outcompeted. A sleeker, more efficient, or more popular synonym muscles it out of the collective vocabulary. We rarely say forsooth when we can say “indeed,” or perchance instead of “perhaps.” Why use the clunky hitherto when “until now” works just as well? This is linguistic natural selection in action.

The Observers: Who Tracks the Decline?

If no one “decides” a word is dead, who are the people watching it happen? This is the domain of lexicographers—the scholars who compile dictionaries—and data-driven language monitors.

The Role of Lexicographers and Dictionaries

Lexicographers are the historians of language, not its executioners. Their job is to describe how language is used, not to prescribe how it should be used. They don’t kill words; they simply note their passing. In a comprehensive historical dictionary like the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), words never truly disappear. Instead, they are given labels that act as tombstones.

- Archaic: This label signifies a word that is still understood but is rarely used except for stylistic effect (think of words used in poetry or historical fiction, like betwixt or ere).

- Obsolete: This is the official declaration of death. An obsolete word is one that has not been in common usage for a very long time. The OED might mark a word as obsolete if it finds no evidence of its use after a certain date.

How do they know? They use massive digital databases called “corpora,” which contain billions of words from books, newspapers, websites, and transcripts. By tracking a word’s frequency over time, lexicographers can pinpoint the moment its pulse began to fade and when it finally flatlined.

The Language Monitors

Then there are organizations like the Global Language Monitor (GLM), which take a more proactive, media-friendly approach. Using algorithms, the GLM scours the internet, social media, and global news outlets to track word usage in real-time. Each year, they famously release a list of words that have “died.”

Their criteria are specific: a word must have had a significant global presence but then show a sharp and sustained decline in usage. While their pronouncements aren’t “official” in a scholarly sense, they provide a fascinating snapshot of our rapidly changing linguistic fashions.

Ghosts in the Machine: When Words Haunt the Dictionary

The graveyard of words has its share of strange and spooky residents, none more so than “ghost words.” These are words that never truly lived at all. They appeared in dictionaries due to misprints, misunderstandings, or scribal errors and were mistaken for real words.

The most famous example is dord. It appeared in the second edition of Webster’s New International Dictionary in 1934 with the definition “density.” For years, it existed as a legitimate entry until an editor discovered its origin. A slip of paper intended to add the entry “D or d” (as an abbreviation for density) was misread as a single word: “dord.” The ghost was finally exorcised from the dictionary in 1947.

These ghost words are a powerful reminder that dictionaries are human artifacts, susceptible to error, and that a word’s existence is ultimately defined by its use among people, not by its presence on a page.

A Final Farewell?

So, who decides when a word is dead? The answer is a quiet consensus of neglect. A word dies when we, the speakers, stop finding it useful. It perishes when the world it describes no longer exists and when new generations find no reason to resurrect it. Lexicographers are merely the cartographers mapping out the cemeteries.

But this graveyard isn’t a sad place. It’s a testament to the incredible dynamism of language. The death of old words makes way for the birth of new ones, ensuring that our language remains a living, breathing tool, perfectly tailored to describe the world we inhabit today. The next time you use a word, remember the silent history it carries—and the thousands of forgotten words that lie in its shadow.