This single event is the primary reason why English, German, Dutch, and the Scandinavian languages sound so distinct from their relatives like French, Spanish, Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit. It’s the secret code that connects the English word father to the Latin pater, and heart to the Latin cor.

Before the Shift: A Quick Trip to PIE

To understand the shift, we need to go back in time—way back, to around 4500-2500 BCE. We arrive at a place with no written records, only a ghost of a language painstakingly reconstructed by linguists. This is Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the theoretical common ancestor of a vast family of languages spoken from India to Europe.

PIE had a specific inventory of sounds. For our story, we’re interested in its “stops”—consonants made by briefly stopping the airflow in the mouth, like /p/, /t/, and /k/. PIE had three main series of these stops:

- Voiceless stops: *p, *t, *k

- Voiced stops: *b, *d, *g

- Voiced aspirated stops: *bʰ, *dʰ, *gʰ (imagine a /b/ or /d/ followed by a puff of air)

As speakers of PIE migrated across Europe and Asia, their dialects drifted apart. The group that settled in northern Europe began speaking in a way that would have sounded very strange to their cousins. They were systematically changing all their stop consonants. This dialect would become Proto-Germanic, the direct ancestor of English.

The Fairytale Collector Who Cracked the Code

For centuries, scholars noticed similarities between words in different languages, but the connections seemed haphazard. Then, in the early 19th century, a German philologist and fairytale collector named Jakob Grimm (yes, one of those Brothers Grimm) noticed the chaos had a pattern. He wasn’t the very first to spot it, but he was the one who formulated it as a cohesive, predictable set of “laws.” He demonstrated that the consonants in the Germanic languages had shifted away from their PIE origins in a stunningly regular chain reaction.

The Three Acts of the Great Sound Shift

Grimm’s Law can be broken down into a three-part chain shift. Think of it as a game of musical chairs with sounds. When one sound moved, it kicked another sound out of its place, which then took over a third spot.

Act I: Voiceless Stops Go Breathable

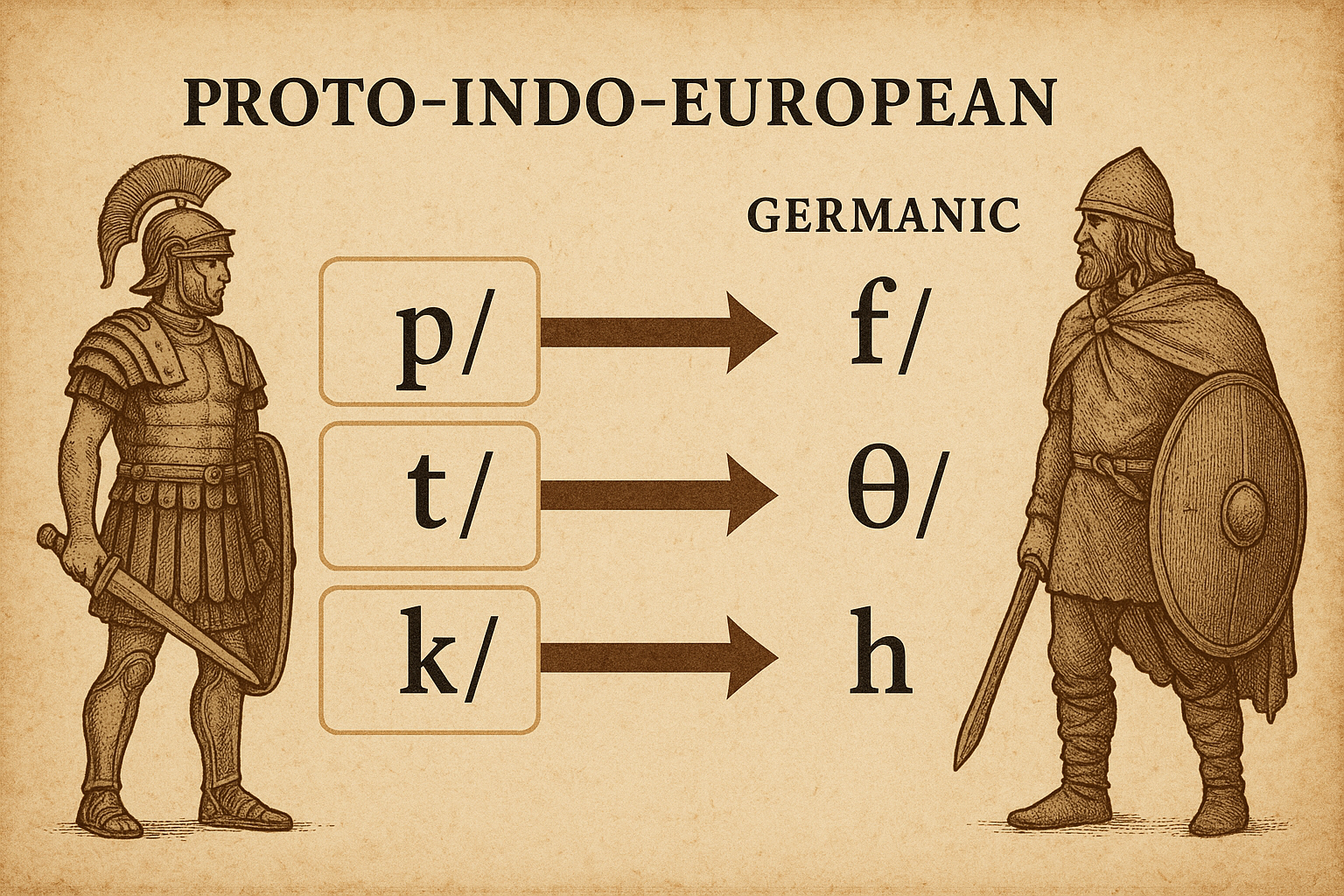

The first change was that PIE’s voiceless stops (*p, *t, *k) became “fricatives” in Proto-Germanic. Fricatives are hissy, breathy sounds made by forcing air through a narrow channel (like /f/, /s/, or the “th” in thin).

- *p → *f

- *t → *θ (the “th” sound in thin)

- *k → *x (a sound like the “ch” in Scottish loch, which later became /h/ in English at the beginning of words)

This single change explains some of the most fundamental differences between Germanic and Romance languages.

| PIE Root | Non-Germanic Cognate (un-shifted) | Germanic Cognate (shifted) |

|---|---|---|

| *pṓds (“foot”) | Latin: pēs, Greek: poús (as in podiatrist) | English: foot, German: Fuß |

| *tréyes (“three”) | Latin: trēs (as in trio) | English: three, Swedish: tre |

| *ḱerd- (“heart”) | Latin: cor (as in cardiac) | English: heart, German: Herz |

Act II: Voiced Stops Lose Their Voice

With the /f/, /θ/, and /h/ sounds now taken, the original voiced stops (*b, *d, *g) moved in to fill the newly vacant voiceless slots (*p, *t, *k).

- *b → *p

- *d → *t

- *g → *k

| PIE Root | Non-Germanic Cognate (un-shifted) | Germanic Cognate (shifted) |

|---|---|---|

| *drew- (“tree, wood”) | Slavic: drevo (as in dryad) | English: tree |

| *déḱm̥ (“ten”) | Latin: decem (as in decimal) | English: ten, Gothic: taihun |

| *ǵénu (“knee”) | Latin: genū (as in genuflect) | English: knee, German: Knie |

Act III: Aspirated Stops Lose Their Breath

Finally, the original voiced aspirated stops (*bʰ, *dʰ, *gʰ) needed a new home. They simplified, losing their breathy aspiration and settling into the now-empty voiced stop slots (*b, *d, *g).

- *bʰ → *b

- *dʰ → *d

- *gʰ → *g

| PIE Root | Non-Germanic Cognate (un-shifted) | Germanic Cognate (shifted) |

|---|---|---|

| *bʰrā́ter- (“brother”) | Sanskrit: bhrā́tā, Ancient Greek: phrā́tēr | English: brother, German: Bruder |

| *dʰwer- (“doorway”) | Sanskrit: dváraḥ, Ancient Greek: thura | English: door, German: Tür |

| *gʰóstis (“stranger, guest”) | Latin: hostis (“enemy, stranger”) | English: guest, German: Gast |

A Defining Moment in Language History

The beauty of Grimm’s Law is its chain-reaction logic. The sounds didn’t just change randomly; they pushed each other along so that the language could maintain distinctions between its core sounds. This systematic shift is the defining feature, the genetic fingerprint, of the Germanic language family.

Of course, it’s not a “law” in the scientific sense. There are exceptions. Another linguist, Karl Verner, later explained many of these exceptions by showing they were conditioned by the position of the stress in the original PIE word (a discovery now called Verner’s Law). But the overarching pattern established by Grimm holds true.

The next time you see a word pair like the French père and the English father, or the Spanish diente and the English tooth, you’re not just looking at two different words. You’re seeing the ancient, echoing legacy of the Great Germanic Sound Shift—a linguistic revolution that carved out a new identity for our language, thousands of years before the word “English” even existed.