Picture a 16th-century galleon slicing through the waves of the Mediterranean. On its deck, a Greek sailor shouts to a Spanish officer, who relays an order to a Tunisian deckhand. None of them share a mother tongue, yet they understand each other perfectly. How? They are speaking the language of the sea—a functional, stripped-down, and vital form of communication known as a maritime pidgin.

Long before English became the world’s default lingua franca, the oceans were a linguistic laboratory. In the confined, high-stakes environment of a ship or a bustling port, the human drive to connect and cooperate gave birth to dozens of these unique contact languages. They weren’t “broken” versions of other languages; they were purpose-built tools, elegant in their simplicity, that laid the very first cables of global communication.

The Original Lingua Franca: Sabir

The story of maritime pidgins begins in the cradle of Western civilization: the Mediterranean Sea. For centuries, this body of water was not a divider but a superhighway for commerce, conflict, and culture. From the Middle Ages until the 19th century, its common tongue was Sabir, a language so influential that its alternative name, Lingua Franca, became the generic term for any language used to bridge a communication gap.

Sabir was a beautiful mess, a testament to the diverse peoples who used it. Its vocabulary was primarily drawn from the Romance languages of the northern coasts—Genoese, Venetian, Spanish, and Portuguese—but it was peppered with words from Arabic, Turkish, and Greek. Its grammar was radically simplified. There were no complicated verb conjugations or gendered nouns. Communication was direct and to the point.

Consider the very name, “Sabir,” which comes from the Romance word for “to know.” A speaker might say “Mi sabir” for “I know” and “Ti sabir” for “you know.” It was a language built for the immediate needs of the dockside marketplace and the ship’s deck: bargaining for goods, giving sailing orders, and sharing news. It was the language of sailors, pirates, merchants, and even slaves, allowing a level of interaction that would have otherwise been impossible.

Riding the Waves of Exploration: Pidgins Go Global

As European powers launched the Age of Exploration, the model of Sabir went global. The same need for a functional, on-the-spot language arose in ports from the Caribbean to the South China Sea. Sailors, already accustomed to linguistic flexibility, became carriers of these pidgins, adapting them to new environments.

Several key maritime-based pidgins emerged during this era:

- Nautical Pidgin English: As the British Empire’s naval power grew, English became a dominant base for many new pidgins. A shared nautical jargon, full of words like “savvy” (from the Portuguese/Spanish sabe, “you know,” likely via Sabir), “starboard,” and “deck,” formed a proto-pidgin used on multi-ethnic ships.

- Chinese Pidgin English: Developed in the 18th century in the port of Canton (modern Guangzhou), this was a classic trade pidgin. British traders and Chinese officials needed a way to do business, and this language was the result. It gave us phrases that have unexpectedly seeped into modern English, most famously “long time no see,” a direct translation of the Chinese phrase 好耐冇見 (hǎo nài mǎo jiàn).

- Russenorsk: A fascinating and rare example, this pidgin was a blend of Russian and Norwegian used by fishermen and traders in the Arctic for over 150 years. It had a tiny vocabulary of only a few hundred words, yet it was stable and effective enough to facilitate a thriving trade in fish and grain. Phrases like “moja på tvoja” (“I speak your language”) show the characteristic blending of grammars.

The Grammar of Necessity

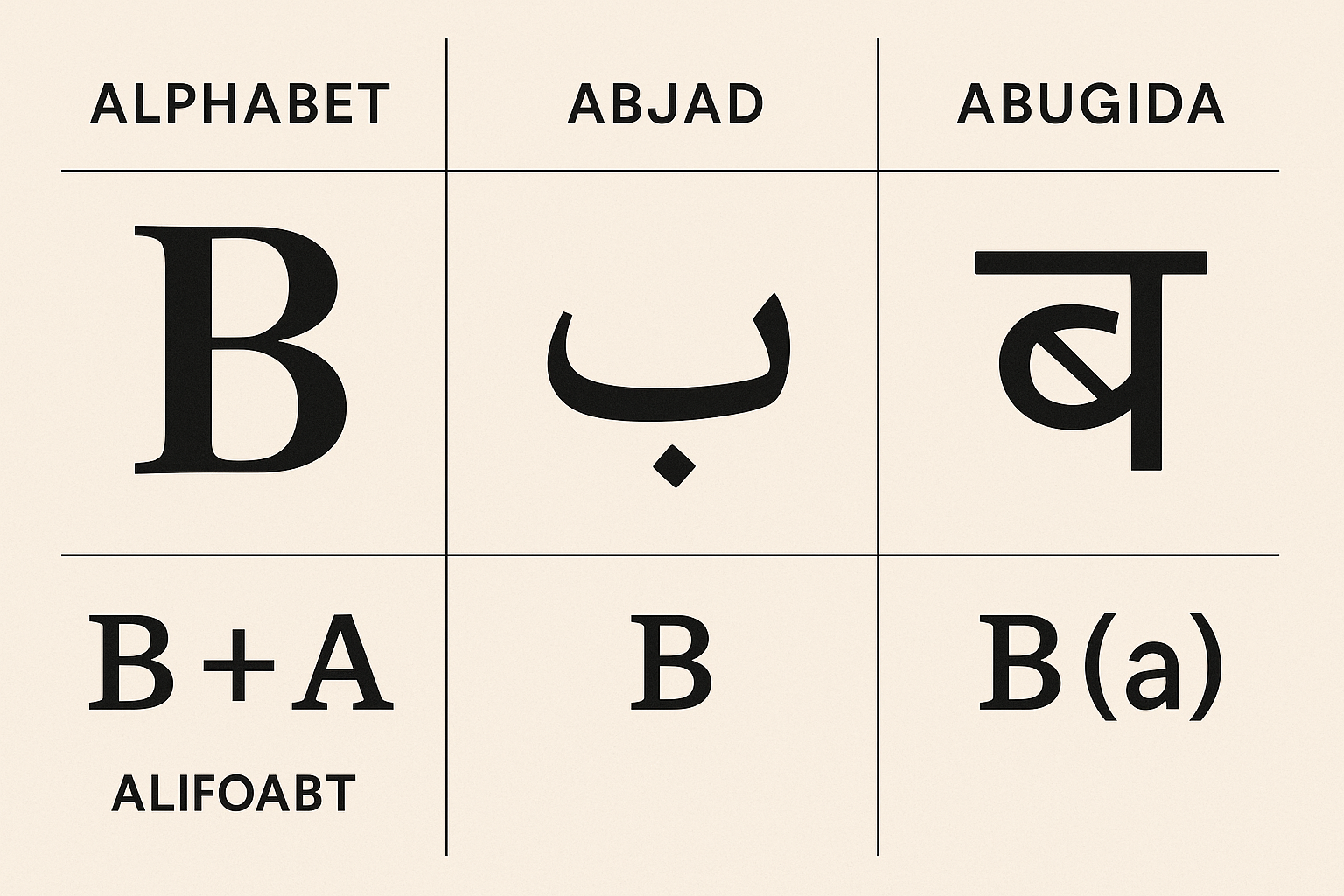

What makes a pidgin a pidgin? These languages are defined by their structure, which is a masterclass in efficiency.

Typically, a pidgin’s vocabulary (its lexicon) is supplied by the socially dominant language, known as the superstrate (e.g., English, Portuguese, French). However, its word order and grammar are often influenced by the native languages of the other speakers, the substrates.

The result is a language stripped of all non-essential features:

- No complex tenses: Time is often indicated with adverbs like “yesterday,” “now,” or “tomorrow” rather than changing the verb itself.

- Reduced pronouns: Instead of “I, me, my,” a pidgin might just use “me” for all three.

- Simplified negatives: A simple “no” placed before a verb often suffices (e.g., “He no go”).

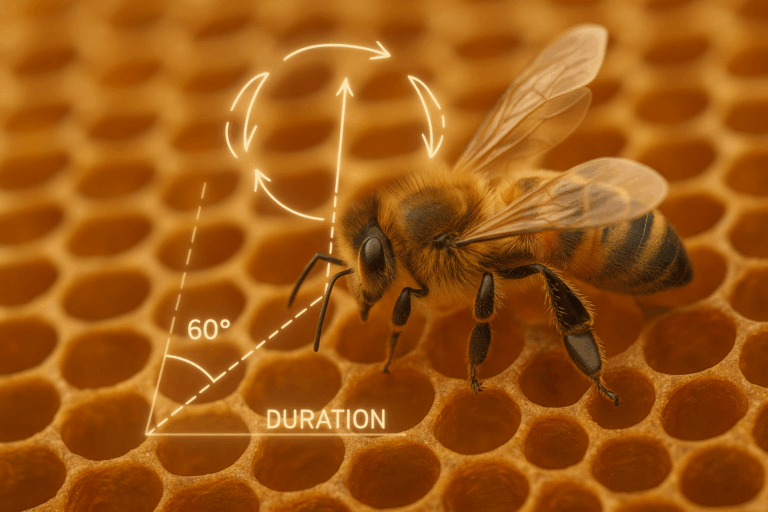

Far from being primitive, this structure reveals a universal human capacity to distill language to its core function: the clear and successful transmission of an idea. They are a monument to cognitive ingenuity, created on the fly by people with an urgent need to understand one another.

From Makeshift Bridge to Mother Tongue

For most of history, pidgins were temporary, utilitarian tools. But what happens when a pidgin becomes so vital that a community uses it for generations? What happens when children are born into an environment where the pidgin is the main language of daily life?

When this occurs, the pidgin undergoes a remarkable transformation. It becomes a creole.

Children who learn a pidgin as their first language naturally expand it. They create more complex grammar, enlarge the vocabulary, and develop the full expressive range of any natural language. The makeshift bridge becomes a permanent, feature-rich highway. Many of the world’s creole languages, such as Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea, Bislama in Vanuatu, and Haitian Creole, have their roots in the pidgins forged by colonialism and trade.

The Echoes of the Sea

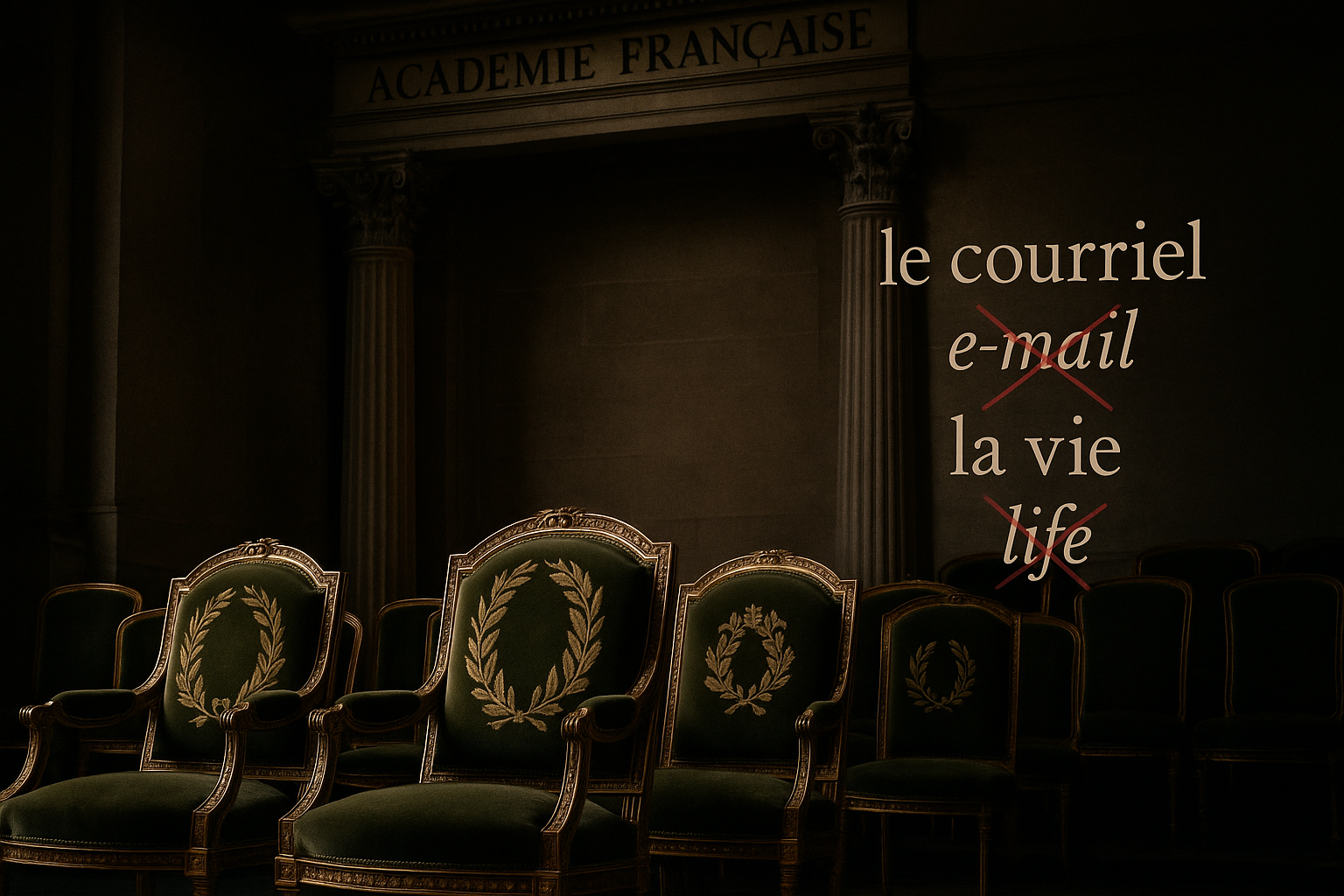

Today, the age of sail and classic maritime pidgins is over. A standardized, globalized form of English, often called “Globish,” has taken their place in international shipping and aviation. Yet, the spirit of the pidgin endures.

Every time we use simplified language to communicate with a non-native speaker, or rely on jargon in a professional field, or even text in shorthand, we are channeling the same linguistic principle: adapt the language to the context to achieve understanding. The maritime pidgins were the original architects of this global mindset.

They are a powerful reminder that language is not a static set of rules but a living, breathing tool for connection. The language of the sea tells a story of human resilience, ingenuity, and our deep, abiding need to communicate—a need so strong that, when faced with a barrier, we will simply invent a new way to speak.