Picture a language where the nouns belong to one family, but the verbs belong to another, entirely different one. A language where you might say “the man” in a way derived from French, but “is walking” in a way derived from Cree. This isn’t a linguistic thought experiment; this is Michif, the traditional language of the Métis people and one of the most structurally unique languages on Earth.

Michif is more than just a curiosity for linguists. It is the spoken soul of a nation, a living testament to a history of cultural fusion, and a powerful symbol of a proud, distinct identity forged on the plains of North America.

A Language Born from a New Nation

To understand Michif, you must first understand the Métis. The Métis people emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries from the relationships between European fur traders (primarily French-Canadian voyageurs) and First Nations women (most often Cree, but also Saulteaux/Ojibwe and others). They were not considered European, nor were they First Nations. They were a new people, a distinct Indigenous nation with its own culture, traditions, and, eventually, its own language.

The Métis homeland, stretching across the Canadian Prairies and into the northern United States, became a crucible of cultures. French, Cree, English, and Ojibwe were all spoken. From this linguistic melting pot, Michif arose, not as a simplified trade pidgin, but as a full-fledged, complex language that perfectly mirrored the dual ancestry of its speakers.

The Unconventional Blueprint: Weaving French and Cree

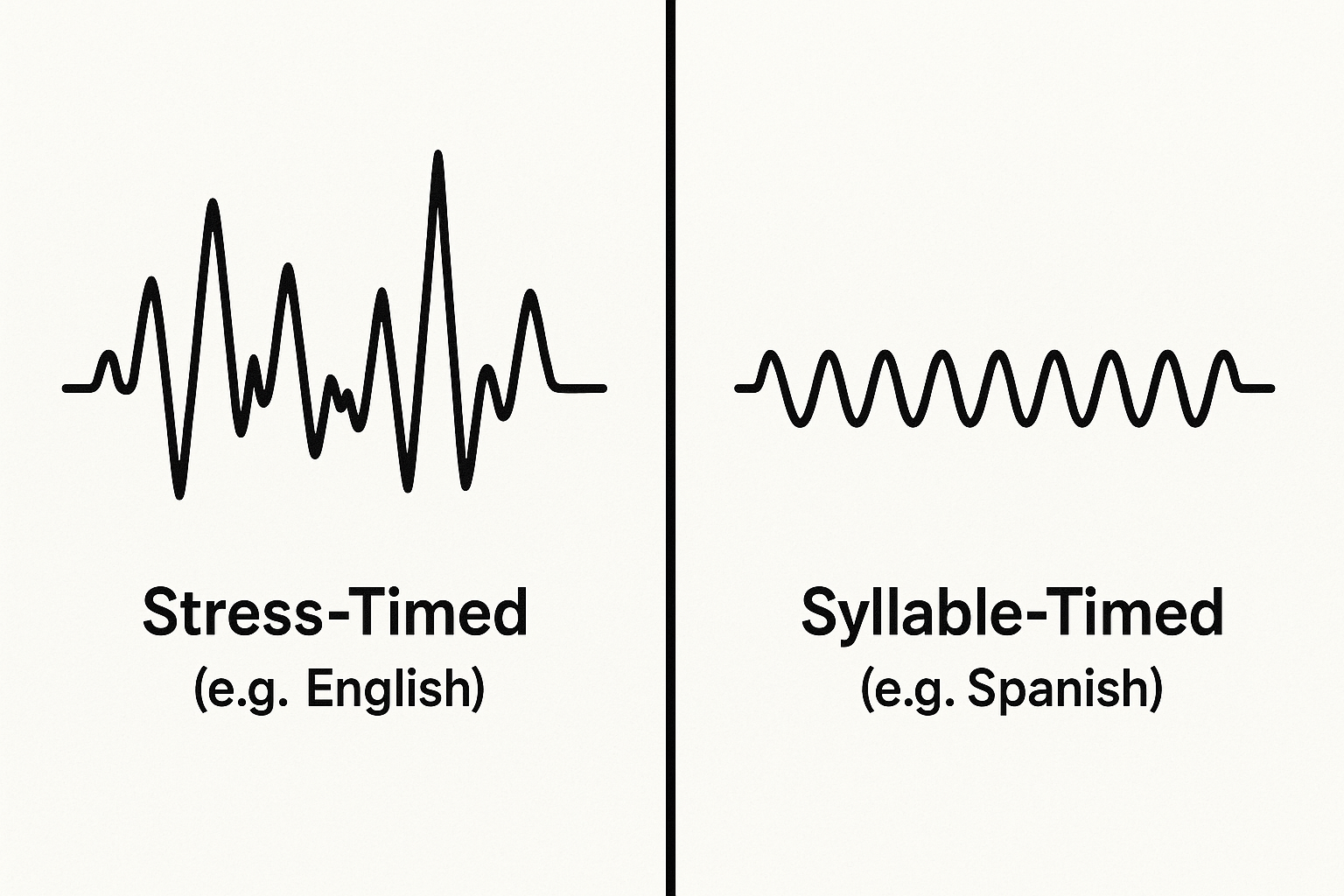

What makes Michif so fascinating to linguists is its highly systematic and unusual structure. Most mixed languages borrow vocabulary or grammatical features, but Michif splits its core components right down the middle, drawing from two different language families: Algonquian (from Plains Cree) and Indo-European (from Canadian French).

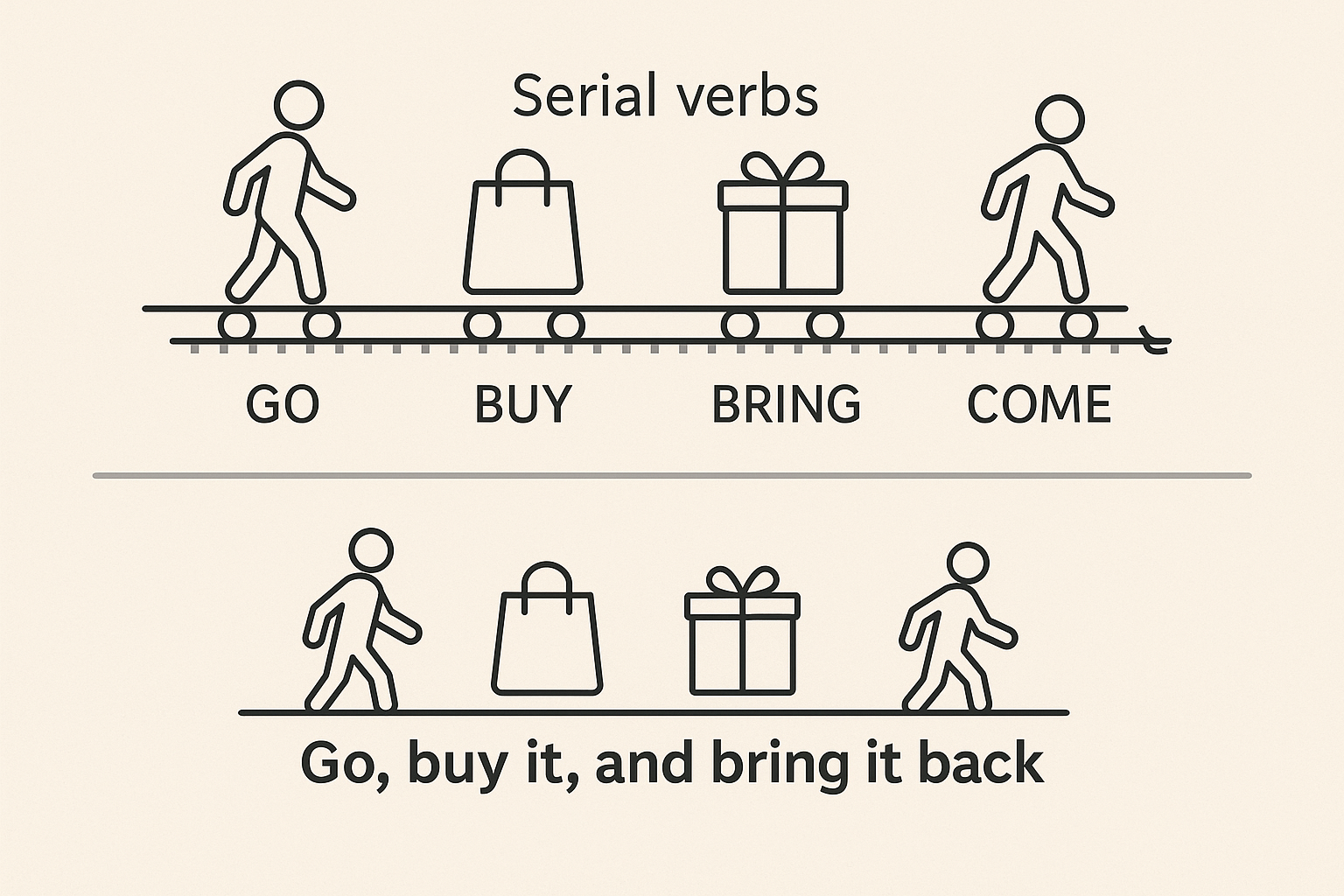

The division of labour is remarkably consistent:

- The Noun System is French: Nearly all nouns, articles (li for “the” masculine, la for “the” feminine), adjectives, and possessives are derived from French.

- The Verb System is Cree: The verbs—the action and grammatical engine of the language—are almost entirely from Plains Cree. This is significant because Cree has a highly complex polysynthetic verb structure, where a single verb can be a complete sentence, packed with information about the subject, object, tense, and mood.

Let’s look at a simple example to see this in action:

Michif: La fiy dâñs-iw.

Meaning: The girl is dancing.

Here, “La fiy” (“the girl”) is clearly from the French “La fille.” But the verb “dâñs-iw” is a Cree construction. It takes the root “dance” (borrowed from French) and applies a classic Cree verb ending (-iw) that indicates a third-person singular subject (“he/she/it is dancing”).

Consider another sentence:

Michif: Chi-wâpam-âw li vyeu.

Meaning: You see the old man.

Here, the noun phrase “li vyeu” (“the old man”) comes from French “le vieux.” The verb, however, is pure Cree grammar. “Chi-wâpam-âw” breaks down into Cree components: chi- (you), -wâpam- (the root for “see”), and -âw (an ending indicating you are seeing a living third person). The entire grammatical framework for the action is Cree, while the object being acted upon is French.

This isn’t random mixing. It’s a stable, rule-governed system. Question words (like tânte, “where?”), demonstratives (like awa, “this”), and personal pronouns are typically Cree, while numerals and prepositions are often French. Michif didn’t simplify its parent languages; it preserved the immense complexity of Cree verb morphology and the gendered noun system of French, weaving them together into a new, intricate whole.

More Than Words: A Symbol of Identity

For the Métis people, Michif is the “language of two souls.” It is the audible manifestation of their dual heritage. It is not half-French and half-Cree; it is fully Métis. Speaking Michif is a declaration of this unique identity, a connection to ancestors who navigated life between two worlds and created a new one.

The language encapsulates a worldview. The French-derived nouns represent the tangible world of objects and things acquired through the fur trade, while the Cree-derived verbs represent the world of action, relationships, and being—the grammatical heart of Indigenous ways of knowing.

Louis Riel, the great Métis leader, famously said, “My people will sleep for one hundred years, but when they awake, it will be the artists who give them their spirit back.” Today, it is the artists, the elders, the teachers, and the language keepers who are breathing new life into Michif, reawakening that spirit.

The Fight for Survival

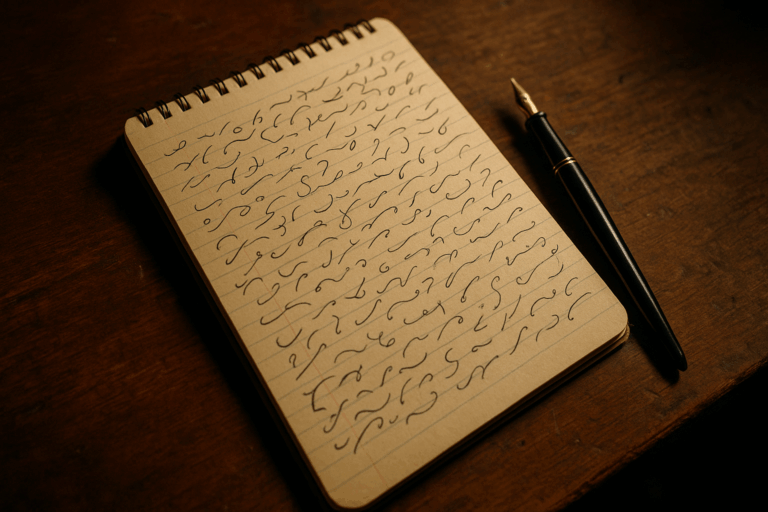

Like so many Indigenous languages, Michif is critically endangered. The number of fluent first-language speakers is tragically low, estimated to be only a few hundred, most of whom are elders. Generations of assimilationist policies, the trauma of residential schools, social stigma, and the dominance of English and French led to a steep decline in its use.

But the story of Michif is not over. Across the Métis homeland, revitalization efforts are underway. Organizations like the Gabriel Dumont Institute and the Louis Riel Institute are developing dictionaries, apps, and educational resources. Communities are hosting language nests and master-apprentice programs, pairing elders with young learners. Every new speaker, every reclaimed word, is a victory.

Michif is a linguistic treasure that challenges our very definition of how languages are formed. It shows us that languages are not static relics but dynamic, living entities that adapt and innovate. More importantly, it stands as the proud, resilient voice of the Métis Nation—a language that speaks of history, identity, and the beautiful complexity of being born of two worlds.