Old Prussian was a unique Baltic language, a cousin to modern Lithuanian and Latvian, spoken along the southeastern coast of the Baltic Sea in what is now parts of Poland, Lithuania, and the Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia. For centuries, its speakers, the Old Prussians, were a collection of proud, pagan tribes. But their fate, and the fate of their language, was sealed in the 13th century with the arrival of the Teutonic Knights.

The Arrival of the Sword

The Northern Crusades are a lesser-known, but no less brutal, chapter of medieval history. While crusaders marched to the Holy Land, another military-religious order, the Teutonic Knights, turned their attention to the last remaining pagan peoples of Europe. Invited in 1226 by a Polish duke to help subdue the pagan Prussians, the Knights saw a golden opportunity not just for conversion, but for conquest.

What followed was not a gentle mission of evangelism, but a century-long campaign of invasion, subjugation, and colonization. The Knights built imposing brick castles, fortresses that served as bases for their military operations and as symbols of their unyielding power. The Prussian tribes fought back fiercely, but they were ultimately overwhelmed by the superior military organization and technology of the crusading state.

This wasn’t just a political conquest; it was a cultural one. The goal was to replace the Prussian way of life, their pagan beliefs, and their very language with a new German Christian order.

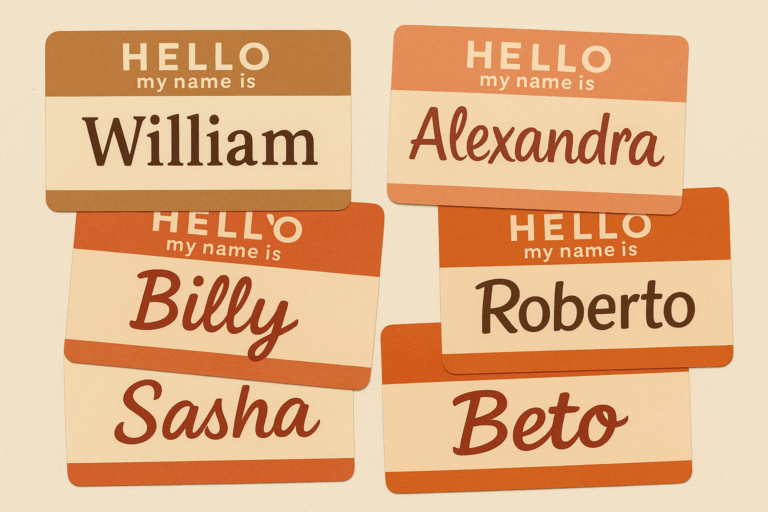

As the Teutonic Order consolidated its power, the Old Prussian language was put under immense pressure. German became the language of the ruling class, of the church, of law, and of commerce. To get ahead—or even just to survive—one had to learn German. Prussian lands were confiscated and given to German-speaking settlers. Speaking Old Prussian became a mark of a conquered, rural, and powerless populace.

For centuries, the language clung on in isolated villages and rural communities. But its fate was sealed. The last native speaker of Old Prussian is thought to have died sometime around the year 1700, extinguishing the language forever.

Whispers from the Past: The Surviving Fragments

How do we know anything about a language that has no speakers and left behind no grand literary works? We piece it together from scraps, from precious fragments that survived the wreckage of history. For Old Prussian, our knowledge comes primarily from a handful of invaluable sources.

The Elbing Vocabulary

Our most important window into the Old Prussian lexicon is the Elbing Vocabulary. Discovered in 1825 in a manuscript belonging to a merchant from Elbing (modern-day Elbląg, Poland), this document is a German-to-Prussian wordlist containing 802 words. Likely compiled around the year 1400 for a German speaker trying to communicate with the locals, it gives us a raw, unfiltered glimpse into the language. It contains words for the everyday world:

- kērmens: body

- tāws: father

- genno: wife/woman

- sāls: salt

- assaran: lake

- swāigstan: star

Without the Elbing Vocabulary, our understanding of Old Prussian would be tragically impoverished. It is the bedrock of all study into this lost language.

The Catechisms

In a profound twist of historical irony, another key source for Old Prussian comes from the very institution that helped destroy its culture: the Church. In the 16th century, during the Protestant Reformation, the new Lutheran Church sought to bring its message to the last remaining Prussian speakers in their native tongue. This led to the translation of three catechisms.

While these texts are invaluable, they are not perfect sources. They are translations, not original compositions, and their grammar and phrasing are heavily influenced by their German source material. The translators themselves sometimes struggled, as evidenced by notes and inconsistencies. Yet, they provide us with the only examples of connected Old Prussian sentences, moving beyond simple wordlists into the realm of grammar and syntax.

A Linguistic Autopsy: What We Lost

Studying these fragments is like performing a linguistic autopsy. What we find is a language that was remarkably archaic, preserving features that had been lost in its sister languages, Lithuanian and Latvian. This makes its extinction an even greater tragedy for historical linguists.

Old Prussian was part of the Western Baltic branch of the language family, while Lithuanian and Latvian form the Eastern Baltic branch. Some of its distinct, conservative features included:

- Retention of the neuter gender: Like Latin or German, Old Prussian had three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter). Both Lithuanian and Latvian later lost the neuter. For example, the Elbing list gives assaran (lake) as a neuter noun.

- Archaic Vocabulary: Many Old Prussian words appear closer to the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root than their modern Baltic counterparts. For instance, the Old Prussian word for ‘fire’ was agnis, strikingly similar to Sanskrit agníḥ and Latin ignis. The Lithuanian equivalent is ugnis.

- Distinct Phonology: It retained the “di” and “ti” sounds that shifted to “dž” and “č” in Lithuanian and “ž” and “š” in Latvian.

Let’s look at a quick comparison to see its place in the family:

| English | Old Prussian | Lithuanian | Latvian |

|---|---|---|---|

| God | deiws | dievas | dievs |

| Hand | rankan | ranka | roka |

| Eye | ackis | akis | acs |

A Ghost in the Family Tree

The story of Old Prussian is a stark and brutal reminder that languages are not just abstract systems of grammar; they are the living breath of a people. Their survival is inextricably linked to the fate of their speakers. The Old Prussians were not assimilated slowly; they were conquered. Their language did not fade away; it was suppressed and ultimately extinguished by force.

Today, Old Prussian exists only as a “ghost” branch on the Baltic language family tree—a collection of whispers pieced together from medieval wordlists and religious translations. It is a testament to a lost world and a chilling lesson in how quickly and completely a unique human voice can be silenced by the sword.