Have you ever found yourself humming along to an Italian opera, feeling the effortless flow of the melody, even if you don’t speak a word of the language? Or have you wondered why so many Swedish, Dutch, and Korean artists choose to write and perform global hits in English? It’s not just about market access; it’s about a fascinating linguistic concept known as “singability.”

The singability of a language is its natural aptitude for being set to music. It’s the reason some languages seem to glide out of a singer’s mouth while others feel more percussive or cumbersome. This quality isn’t magic—it’s rooted in the science of phonetics, the study of speech sounds. Let’s peel back the curtain on the phonetics of pop and explore what makes a language ready for the stage.

The Golden Ratio: Vowels to Consonants

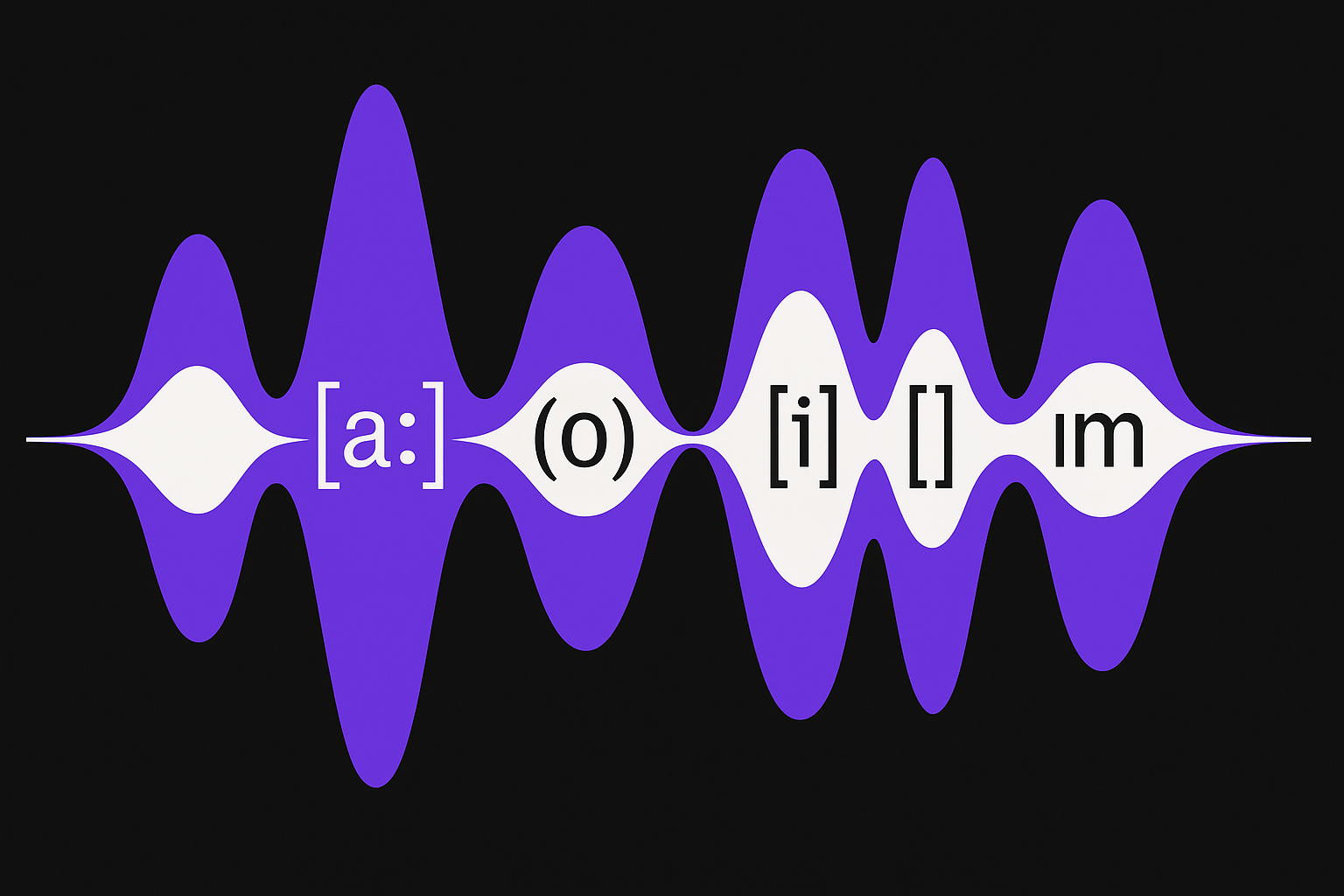

At the heart of singability is the interplay between vowels and consonants. Think of vowels (a, e, i, o, u, and their many variations) as pure, resonant tones. To produce them, your vocal tract is open, allowing air and sound to flow freely. For a singer, vowels are gold. They are the sounds you can sustain, bend, and fill with vibrato. They are the canvas for long, powerful notes—the soul of a melody.

Consonants, on the other hand, are sounds created by obstructing that airflow. Whether it’s the percussive pop of a ‘p’, the hiss of an ‘s’, or the hard stop of a ‘t’, consonants are essentially musical noise. They provide rhythm, definition, and clarity to lyrics, but they interrupt the pure melodic line.

Languages with a high vowel-to-consonant ratio are often perceived as more melodious. This is the secret to Italian’s reign in opera. Words like amore (a-mo-re) or canzone (ca-nzo-ne) are dominated by open vowel sounds, allowing singers to sustain notes beautifully. Compare that to a German word like Streichholzschächtelchen (a little matchbox), which is packed with consonant clusters that are tricky to articulate, let alone sing with soaring power.

This isn’t a judgment on the beauty of a language—German is fantastic for the crisp, rhythmic delivery required in lieder or the aggressive punch of industrial metal—but for legato-style singing, the more vowels, the better.

Building Blocks of Rhythm: Syllable Structure

Beyond individual sounds, we have to look at how they’re put together. This is the domain of phonotactics—the rules governing how sounds can be combined to form syllables in a given language. Some languages prefer very simple structures, while others embrace complexity.

The most basic and common syllable structure across all languages is CV (Consonant-Vowel). It creates a clear, predictable, and rhythmic flow. Again, Italian and Spanish excel here, with many words following a simple CV-CV pattern, like casa (ca-sa) or musica (mu-si-ca). Japanese is even more rigid in this respect. Most of its syllables are either a lone vowel or a CV pair, as in ka-ra-o-ke. This structure gives Japanese music a distinct, staccato-like clarity that works perfectly for pop and anime themes.

English, however, is a phonotactic free-for-all. It allows for incredibly complex syllables with dense consonant clusters. Take the one-syllable word strengths (CCCVCCC). Trying to sing that word clearly while holding a note is a phonetic workout. These clusters can break up a smooth melodic line, forcing singers to deliver them quickly and percussively.

This very complexity, however, is also a secret to English’s versatility. While challenging for opera, these consonant-heavy words are perfect for genres like hip-hop and rock, where rhythmic punch and lyrical density are prized over smooth, flowing melodies.

The Music Within: Prosody and Intonation

Every language has its own inherent music, a pattern of rhythm, stress, and pitch known as prosody. This is why some languages are described as “sing-songy” even when spoken.

Languages are often categorized by their rhythmic patterns:

- Syllable-timed languages (like Spanish, Italian, and French) give roughly equal time to each syllable, creating a steady, machine-gun-like rhythm. This predictable cadence makes it very easy to set lyrics to a consistent musical beat.

- Stress-timed languages (like English, German, and Russian) give more time to stressed syllables, while unstressed syllables are shortened and squashed together. This creates a more uneven, “Morse code” rhythm (DA-da-da-DA-da-DA). This syncopated feel aligns perfectly with the backbeat-driven rhythms of pop, rock, and blues.

Then there’s the challenge of tonal languages like Mandarin, Cantonese, and Vietnamese. In these languages, the pitch contour of a word determines its meaning. For example, in Mandarin, mā (high level tone) means “mother,” while mǎ (falling-rising tone) means “horse.” A songwriter can’t simply create a melody and fit the words to it; the melody must respect the lexical tones of the lyrics, or risk changing their meaning entirely. This is a profound constraint, but one that can lead to a beautiful and intricate fusion of linguistic and musical melody.

Language Spotlights: Who “Sings” Best?

The Pop Chameleon: English

English dominates the global music charts for many reasons, including cultural and economic history. But phonetically, it’s a “Goldilocks” language. It has a rich inventory of about 20 vowel sounds, allowing for melodic variety. Its mix of simple and complex syllables makes it versatile for both ballads and rap. And its large vocabulary of short, punchy, monosyllabic words (love, heart, beat, fire, stop, feel) is perfect for crafting unforgettable pop hooks. Its stress-timed rhythm is the bedrock of Western pop music.

The Opera Star: Italian

As we’ve seen, Italian is practically designed for classical singing. Its high vowel count, pure vowel sounds (no complex diphthongs like the “oi” in English “boy”), and simple CV syllable structure make it the ideal vehicle for the long, powerful, and emotive lines of opera.

The Pop-Writing Powerhouse: Swedish

This one is a bit of a curveball. Artists like ABBA and songwriters like Max Martin have made Sweden a pop music factory, but they write in English. Why? Beyond excellent English education, Swedish itself is a very musical language, with a distinct “pitch accent” that gives it a sing-song quality. It’s theorized that being a native speaker of such a prosodically rich language attunes one’s ear to crafting strong, memorable melodies—a skill they then apply to the global lingua franca of pop, English.

Conclusion: A Chorus of Possibilities

Ultimately, no language is phonetically “superior” to another. “Singability” is entirely dependent on the musical context and genre. The consonant clusters of Polish might be perfect for a death metal band. The rhythmic flow of Swahili can create incredible hip-hop. The tonal subtleties of Thai can inspire breathtakingly intricate folk music.

The phonetics of a language don’t limit its musical potential; they define its unique voice. So the next time you listen to a song in a language you don’t know, pay attention not just to the melody of the instruments, but to the music of the words themselves. You’ll discover a whole new layer of artistry, rhythm, and soul.