Take a simple sound, like the ‘p’ in “pot.” You push air from your lungs, your lips pop open, and a little puff of breath follows. It’s one of the first sounds we learn as children. Now, imagine a version of that ‘p’ that’s sharper, crisper, and made not with a gentle puff of air from the lungs, but with a contained, pressurized burst right from your throat. It’s a sound with an edge, a pop that feels more like a cork leaving a bottle than a simple consonant.

Welcome to the world of ejectives, the pressure-cooker consonants of human language. Far from being a linguistic oddity, these emphatic sounds are a key feature in roughly 20% of the world’s languages, dotting the map from the rugged Caucasus mountains to the highlands of the Americas and across parts of Africa. They are a powerful reminder that the air we use to speak doesn’t always have to come from our lungs.

So, What Exactly *Is* an Ejective?

To understand an ejective, let’s first think about how we normally make a consonant like ‘p’, ‘t’, or ‘k’. The technical term for this is a pulmonic egressive sound. Pulmonic means it uses air from the lungs, and egressive means the air is flowing outwards. It’s the default power source for speech in English and most other European languages.

Ejectives flip the script. They use a glottalic egressive airstream mechanism. Let’s break that down:

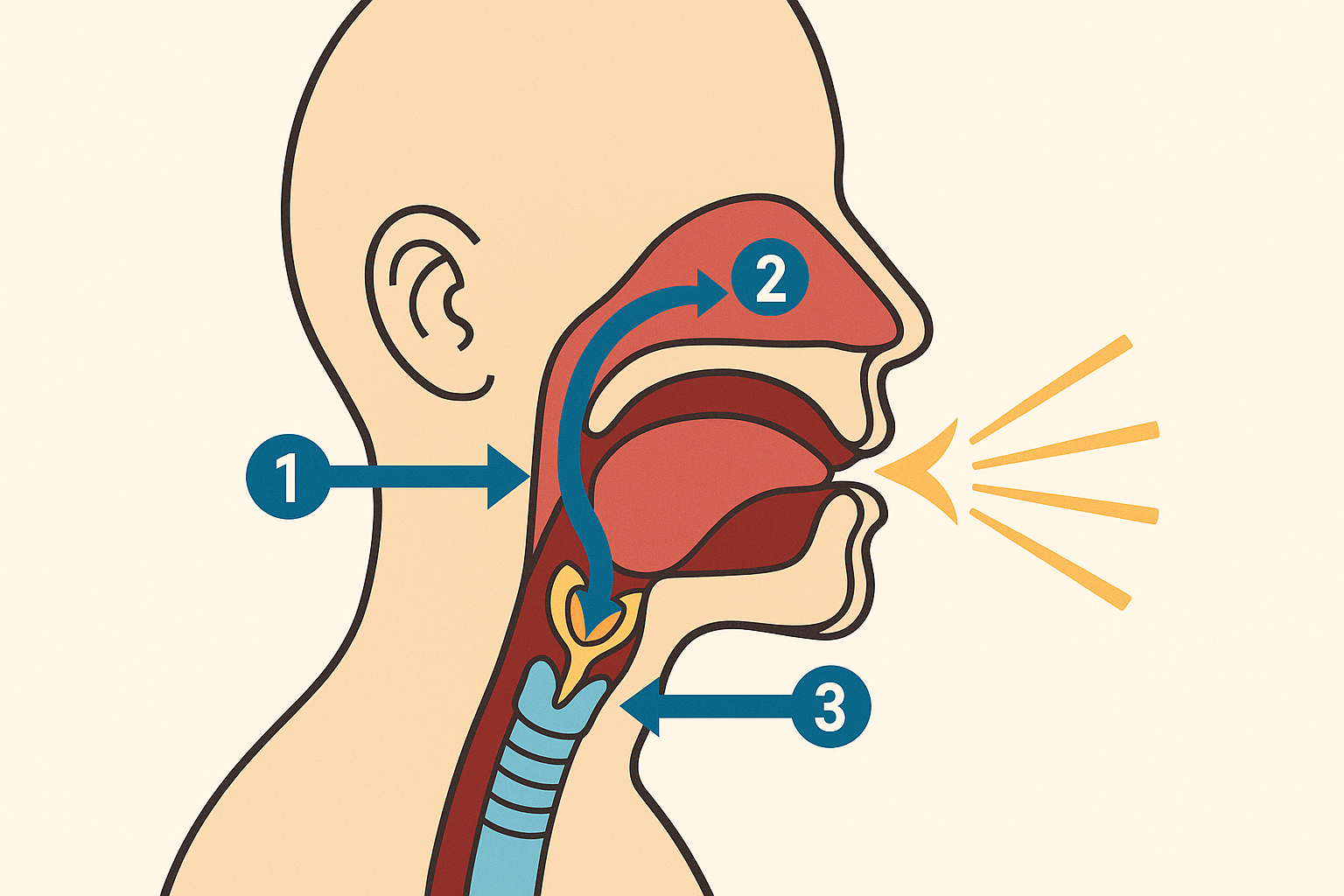

- Glottalic: The action starts at the glottis—the space between your vocal cords in your larynx (or voice box).

- Egressive: The air still flows outwards.

Making an ejective is like performing a tiny, precise phonetic stunt inside your mouth. It involves a sequence of four key steps:

- Closure in the Mouth: First, you make the shape for a regular consonant. For an ejective p’, you close your lips. For a t’, you place your tongue against the ridge behind your teeth. For a k’, you raise the back of your tongue to the soft palate.

- Closure in the Throat: At the same time, you close your glottis, sealing your vocal cords shut. This traps a pocket of air in the space between your throat and your mouth. This is the crucial step—no air can get in from the lungs, and no air can escape.

- Building the Pressure: Now for the “pressure-cooker” part. You rapidly raise your entire larynx (you can feel your Adam’s apple move up if you try this). Since the air is trapped in a fixed space, this upward movement dramatically compresses it.

- The Release: Finally, you release the closure in your mouth (your lips for p’, your tongue for t’ or k’). The highly pressurized air bursts out with a distinctively sharp, popping sound. Only after this pop does the glottis open to allow normal airflow to resume.

The result is a sound that has no voicing (the vocal cords aren’t vibrating) and no aspiration (that puff of lung air). It’s just a clean, sharp crackle of sound. In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), ejectives are marked with an apostrophe-like modifier, like pʼ, tʼ, and kʼ.

Hearing the Difference: A Sonic Showcase

Describing an ejective is one thing; hearing it is another. The difference between a regular stop consonant and its ejective cousin is stark. Let’s compare the ‘k’ sound in a few contexts.

The ‘k’ Family:

- Aspirated [kʰ]: The ‘k’ in the English word “key.” You can feel a significant puff of air if you hold your hand in front of your mouth. [Listen Here]

- Unaspirated [k]: The ‘k’ in the English word “sky.” The ‘s’ sound before it removes the aspiration. There’s no puff of air. [Listen Here]

- Ejective [kʼ]: The classic ejective. It has a sharp, almost “clicky” quality to it, completely different from the other two. It’s the sound you might make to imitate a water droplet. [Listen to kʼ]

This principle doesn’t just apply to stops. Many languages also have ejective affricates (like the ‘ch’ in “church,” but ejective: tʃʼ) and even ejective fricatives (like an ejective ‘s’: sʼ), which sound like a sharp hiss overlaid with a pop.

A World Tour of Ejectives

While you won’t find ejectives in Spanish, French, or Japanese, they are linguistic superstars in other parts of the world.

The Caucasus: Ground Zero for Ejectives

The languages of the Caucasus region (like Georgian, Chechen, and Circassian) are famous for their complex consonant systems, and ejectives are the main event. Georgian is a perfect example, as it features a three-way distinction for many of its stops: voiced (like b), voiceless aspirated (like pʰ), and ejective (like pʼ).

This creates sets of words that are distinguished *only* by this feature:

- ბარი (bari) – a voiced /b/, means “a flat plain”

- ფარი (pari) – an aspirated /pʰ/, means “a shield”

- პარი (pʼari) – an ejective /pʼ/, means “a flutter” or “to fly”

To a native Georgian speaker, these three sounds are as different as ‘b’, ‘p’, and ‘f’ are to an English speaker.

The Americas: A Continental Feature

Ejectives are extremely common throughout the indigenous languages of North, Central, and South America. They are found in the Na-Dene languages (like Navajo), Salishan languages of the Pacific Northwest, and Mayan languages.

In the Andes, Quechua (the language of the Inca Empire) also uses ejectives to create crucial distinctions. The word for “bread” is tʼanta, with a sharp ejective tʼ. This contrasts with tanta, with a plain ‘t’, which means “a meeting” or “a pile.” Mixing them up could lead to some confusing conversations at the market!

Africa and Beyond

In Africa, ejectives are a defining feature of the Ethio-Semitic languages, including Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia. They are also prominent in Hausa, a major language of West Africa, and in many of the Khoisan languages of Southern Africa, where they coexist alongside the famous click consonants.

The ‘Feel’ of an Ejective Language

Beyond the technical details, the presence of ejectives gives a language a distinct aesthetic texture. Languages rich in ejectives often sound more percussive and punctuated than languages without them. While a language like Italian might flow with a smooth, sonorous quality, a language like Kʼicheʼ (a Mayan language) has a crisp, popping rhythm.

This isn’t a value judgment—it’s a reflection of the different phonetic tools each language employs. Ejectives expand a language’s inventory of sounds, allowing for more contrasts without having to resort to different vowels or tones. They add a layer of complexity and expression that is fascinating to listen to, even if you don’t understand the words.

So, the next time you’re exploring the sounds of the world’s languages, listen for that sharp pop. It’s more than just an exotic sound; it’s the mark of a completely different way of powering speech. It’s the sound of the pressure being released, a tiny, perfectly controlled explosion that helps shape the identity of thousands of linguistic communities across the globe.