You’re in a meeting, and a colleague presents their findings: “So, the data shows a clear upward trend? And our target demographic is responding positively to the new campaign?” They’re stating facts, but each sentence lilts upwards, transforming a declaration into something that sounds suspiciously like a question.

If you’ve noticed this pattern, you’re not alone. Welcome to the world of High Rising Terminal (HRT), more famously known as “uptalk” or the “High Rising Intonation.” It’s a linguistic feature that has been stereotyped, criticized, and misunderstood for decades. But is it really just a sign of insecurity, or is something much more sophisticated happening in our conversations? Let’s dive into the surprising linguistics of the question that isn’t a question.

What Exactly is Uptalk?

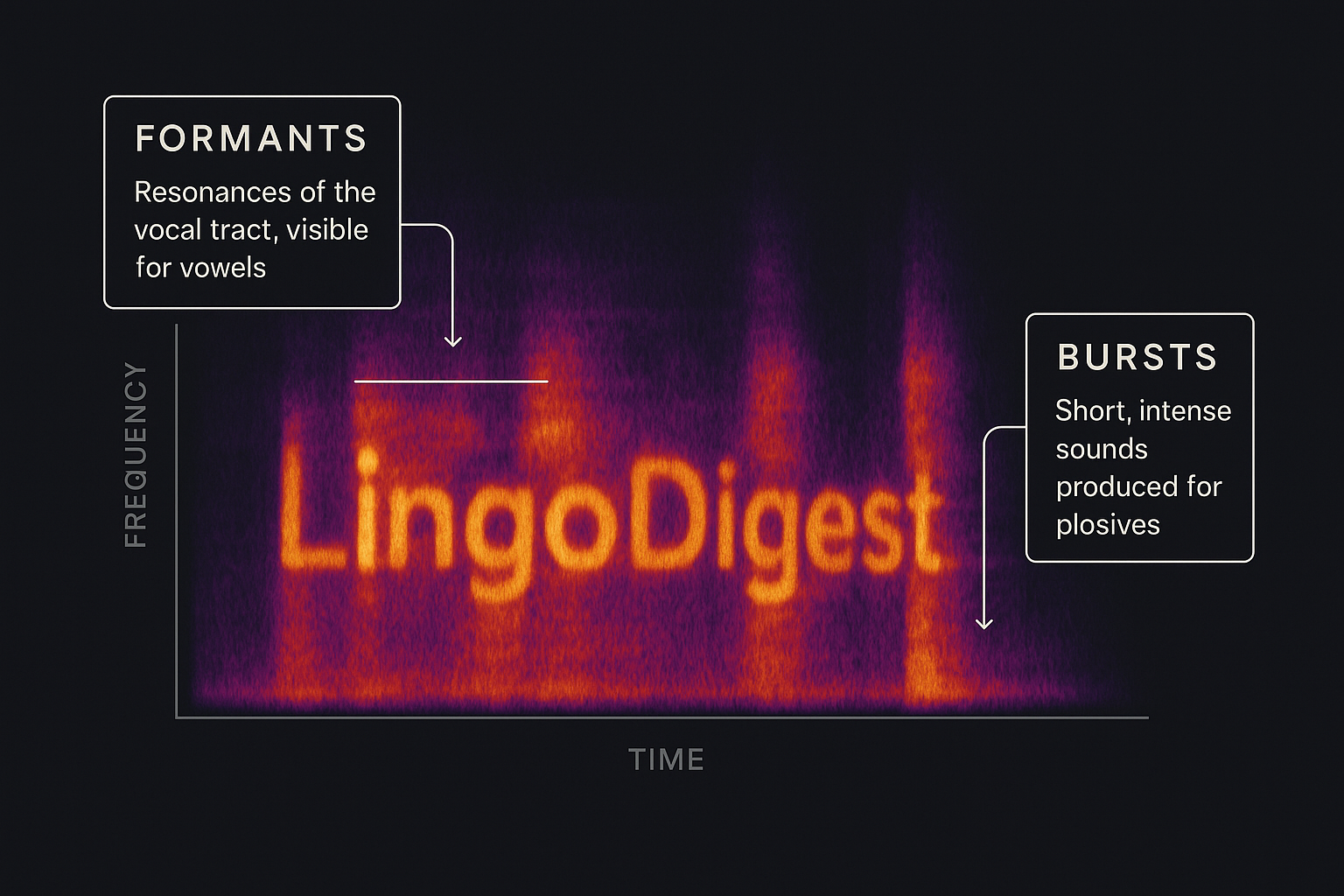

In standard American and British English, intonation follows a predictable pattern. Declarative statements, which state facts, end with a falling pitch. Questions, on the other hand, typically end with a rising pitch.

- Statement (falling pitch): “We are launching the product on Tuesday.”

- Question (rising pitch): “Are we launching the product on Tuesday?”

Uptalk flips this on its head. It applies a rising, question-like intonation to a declarative statement.

- Uptalk (rising pitch): “We are launching the product on Tuesday?”

This final example is grammatically a statement, but the rising pitch changes its pragmatic function—how it’s used and interpreted in a social context. This disconnect between grammar and intonation is what makes uptalk so fascinating and, for some listeners, so jarring.

From the Valley to the World: The Origins of Uptalk

For many, the word “uptalk” conjures a very specific image: the “Valley Girl” of 1980s Southern California. Popularized by Frank Zappa’s song “Valley Girl” and immortalized by films like Clueless, this speech pattern became a powerful stereotype. It was associated almost exclusively with young, affluent, and supposedly air-headed women. The rising intonation was interpreted as a sign of ditziness and a chronic lack of confidence, as if the speaker were constantly seeking approval for her own thoughts.

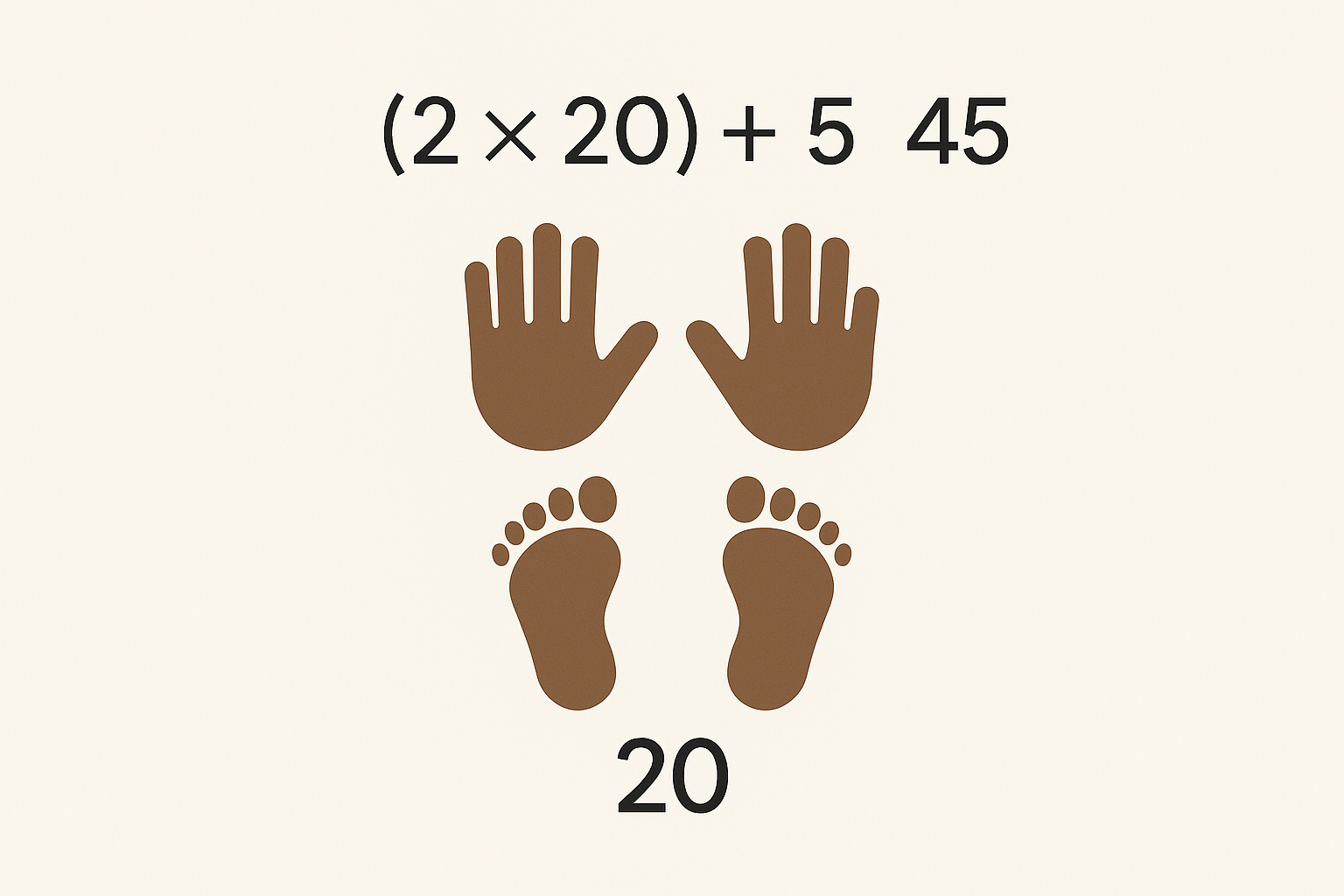

But the real story is much more complex. While the “Valleyspeak” phenomenon certainly propelled uptalk into the global consciousness, linguists have found similar intonational patterns in other dialects of English that predate the 1980s. Notably, Australian and New Zealand English have long featured what’s known as the “Australian Questioning Intonation” (AQI), which functions in a similar way.

Over the past few decades, uptalk has broken free from its geographical and demographic confines. It’s no longer just a feature of young women in California. You can hear it from men and women of all ages, in boardrooms in New York, cafés in London, and call centers in Manila. Its journey from a regional stereotype to a global linguistic feature suggests it’s doing important conversational work.

So, Like, What Does It Mean? The Functions of HRT

If uptalk isn’t just about being uncertain, what is it for? Linguists have identified several key functions that reveal its utility as a sophisticated conversational tool.

1. The Politeness and Inclusion Strategy

Perhaps the most important function of uptalk is to foster a collaborative and non-confrontational atmosphere. By ending a statement with a rising pitch, a speaker can soften a potential command or a bold assertion. Compare these two sentences:

Assertive: “You need to file this report by noon.” (Falling pitch)

Inclusive: “You need to file this report by noon?” (Rising pitch)

The first sounds like a direct order. The second, with its rising intonation, invites confirmation and makes the interaction feel more like a cooperative agreement than a command. It implicitly asks, “Is that okay with you? Do you have any issues with that?” This can be an incredibly useful tool for navigating workplace hierarchies and maintaining social harmony.

2. The “Floor-Holding” Device

Uptalk is also brilliant for storytelling and holding the listener’s attention during a multi-part narrative. The rising pitch at the end of a clause acts as a conversational placeholder, signaling to the listener, “I’m not finished yet, are you still with me?”

Imagine a friend recounting their day:

“So I get to the airport? and my flight is delayed by two hours? So I decide to go get some coffee? and I run into my old college roommate?”

Each rise keeps the listener engaged and signals that another piece of the story is coming. The story only concludes when the speaker uses a final, falling intonation, which signifies “This is the end of my thought.” It’s a way of checking for comprehension and ensuring the audience is ready for the next beat of the story.

3. The Confirmation Check

Of course, the classic interpretation of uptalk—as a way of seeking validation—is sometimes true. When presenting new information, a speaker might use a rising tone to check if the listener understands or agrees. It’s a way of saying, “Am I making sense?” or “Do you follow?”

In this sense, it’s less about the speaker’s own uncertainty about the facts and more about their uncertainty regarding the listener’s state of knowledge. It’s a tool for building common ground before moving on.

The Gender and Power Dynamics of Uptalk

It’s impossible to discuss uptalk without addressing its gendered perception. Because of its “Valley Girl” origins, uptalk is still heavily associated with women, and the judgments that come with it are often sexist. When women use uptalk, they risk being perceived as insecure, unqualified, or even childish. When men use it, it is often not noticed at all or is interpreted as being collaborative and modern.

This double standard highlights a broader linguistic bias. Speech patterns associated with women are often stigmatized and viewed as deficient, while male-dominated patterns are treated as the norm. However, as linguist Penny Eckert points out, these features are often pioneered by young women because they are often the most sensitive to social dynamics and the most innovative in their use of language to navigate them.

A Feature, Not a Flaw

Language is constantly evolving, and uptalk is a prime example of this evolution in action. What began as a stereotyped quirk of a specific subculture has become a widespread tool for managing social interactions in a nuanced way.

So the next time you hear someone end a statement with a rising pitch, pause before you judge. Are they really asking a question? Or are they skillfully holding your attention, politely framing a directive, or building a bridge of shared understanding? More often than not, you’re witnessing a sophisticated linguistic strategy at play—a sign not of uncertainty, but of a deeply social and adaptable communicator.