Ever wonder why English, when spoken, seems to have a completely different musical quality than Spanish? Or why Japanese can sound so steady and even-paced? It’s not just about the different sounds or grammar; it’s about something deeper, something fundamental to the language’s very melody: its rhythm.

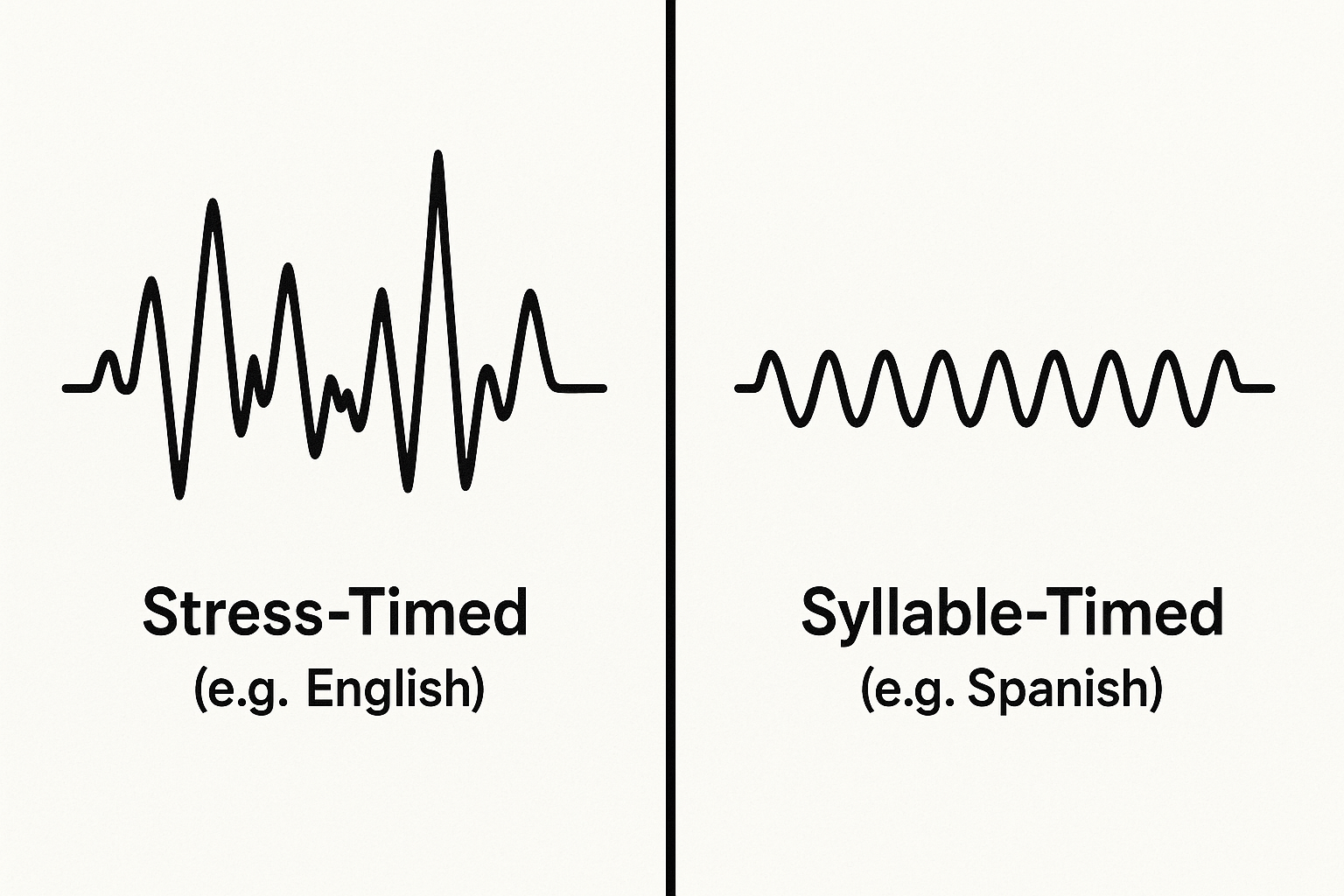

This “beat” of a language is a core concept in phonology, and it helps explain why some languages feel choppy and percussive while others feel smooth and flowing. The primary way linguists categorize this phenomenon is by sorting languages into two main groups: stress-timed and syllable-timed.

What is Linguistic Rhythm?

At its heart, linguistic rhythm is about isochrony (from Greek, meaning “equal time”). The theory of isochrony suggests that languages tend to keep the time between certain phonological units relatively constant. The crucial question is: what unit?

- In stress-timed languages, the interval between stressed syllables is roughly the same.

- In syllable-timed languages, the duration of each syllable is roughly the same.

Think of it like music. A stress-timed language is like a song with a strong, steady drum beat (the stress), with a varying number of quick little notes played in between. A syllable-timed language is more like a metronome, where every single tick is evenly spaced.

Stress-Timed Languages: The Rhythm of the Beat

English is a classic example of a stress-timed language, along with German, Dutch, Russian, and Arabic. In these languages, the stressed syllables are the anchors of an utterance. They are the “beat” of the sentence, and the unstressed syllables are squashed or stretched to fit the time between them.

Consider these two English sentences:

- Cats chase mice. (3 syllables)

- The cats will be chasing the mice. (9 syllables)

Despite the huge difference in syllable count, a native English speaker will say both sentences in a surprisingly similar amount of time. How is this possible?

The Magic of Vowel Reduction

To fit into the rhythmic pattern, unstressed syllables in English are heavily reduced. Vowels often collapse into a weak, neutral sound called a “schwa” (ə), which sounds like the ‘a’ in sofa or the ‘u’ in support. In the second sentence, “the” becomes “thə,” “will be” can become “wəl-bə,” and the “-ing” in “chasing” is quick and light.

This is why an English sentence can sound like a series of peaks (stressed syllables) and valleys (unstressed, reduced syllables). It’s a “da-DUM-da-da-DUM-da-DUM” kind of rhythm.

Syllable-Timed Languages: The Even Pulse

In contrast, syllable-timed languages give each syllable its moment in the sun. Each one receives a roughly equal amount of time, regardless of whether it is stressed or not. This creates a steadier, more staccato rhythm often described as “machine-gun-like.”

Prime examples include the Romance languages (Spanish, French, Italian), as well as Turkish and Cantonese.

Let’s look at a Spanish phrase:

- Me gus-ta el cho-co-la-te. (I like chocolate.)

A Spanish speaker pronounces each of those seven syllables with a clear, consistent duration. There is no major vowel reduction. The ‘o’s and ‘a’s and ‘e’s retain their full, crisp sound. This creates that distinct, even pulse: “da-da-da-da-da-da-da.”

This is why syllable-timed languages often have simpler syllable structures (like Consonant-Vowel, Consonant-Vowel) and fewer of the complex consonant clusters you see in English (e.g., “strengths”).

A Third Way: Mora-Timed Languages

To make things even more interesting, linguists identified a third category that is a refinement of syllable-timing: mora-timed. The most famous example is Japanese.

A “mora” is a unit of sound that determines syllable weight. In Japanese, the rhythm isn’t based on syllables, but on these morae. A simple consonant-vowel combination like ka (か) is one mora. However, adding a long vowel, as in kā (カー, “car”), or a final consonant, as in san (さん), makes the syllable two morae long.

- o-ba-san (おばさん) – “aunt” (4 morae, 4 beats)

- o-bā-san (おばあさん) – “grandmother” (5 morae, 5 beats, the “bā” gets two beats)

This mora-based system is what gives Japanese its incredibly regular and predictable rhythm, and it’s the basis for poetic forms like the haiku, which counts morae (not syllables) in its 5-7-5 structure.

Why This Rhythmic Difference Matters

This isn’t just a fun piece of linguistic trivia; it has profound effects on how we speak, listen, and even create art.

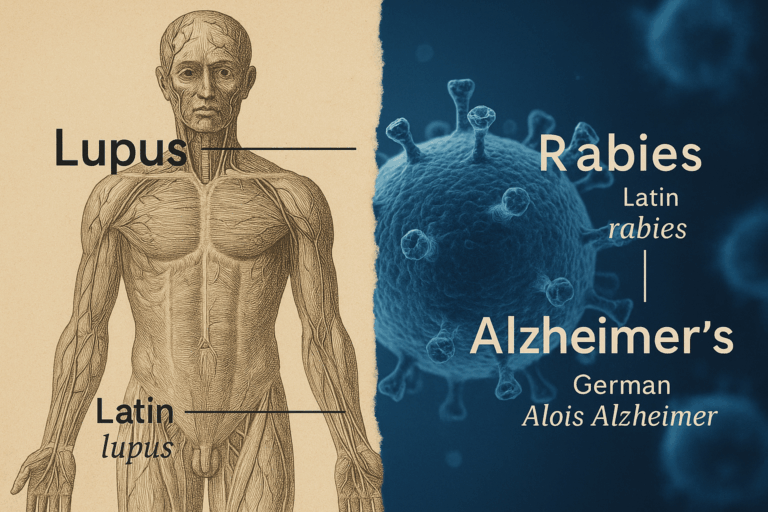

1. Foreign Accents and Pronunciation

The rhythm of speech is one of the biggest contributors to a “foreign accent.” When a native Spanish speaker learns English, they may unconsciously apply syllable-timed rhythm, giving each English syllable equal weight. This can make their speech sound staccato to an English ear.

Conversely, when a native English speaker learns French, they may reduce unstressed vowels and rush through syllables, applying their native stress-timed rhythm. This can make their French sound “muddy” or “slurred” to a native French ear.

2. Listening Comprehension

Your brain is trained to listen for the rhythm of your native language. English speakers subconsciously latch onto the stressed syllables to get the main information of a sentence. This is why we can often understand mumbled or fast speech—as long as the stressed beats are clear. When listening to a syllable-timed language, this strategy fails, and it can feel like being hit with a wall of undifferentiated sound.

3. Poetry and Music

Linguistic rhythm is the backbone of poetry. The metrical feet of English poetry, like iambic pentameter (“To be or not to be, that is the question”), are entirely dependent on patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables.

In contrast, poetry in Japanese (haiku) or French (versification) is based on syllable/mora counts, not stress patterns. This fundamental difference means that translating poetry is not just about words, but about finding a whole new rhythmic structure.

A Spectrum, Not a Switch

It’s important to note that these categories are not absolute. They represent two ends of a spectrum. Some languages, like Polish or Italian, sit somewhere in the middle, exhibiting features of both types. The original theory of perfect isochrony is debated by modern linguists, but the distinction between stress-timing and syllable-timing remains an incredibly useful model for understanding the rhythmic diversity of the world’s languages.

So, the next time you listen to a foreign language, tune out the words for a moment and just listen to the music. Is it a steady metronome or a syncopated drum beat? By hearing its rhythm, you’re beginning to understand the very soul of the language.