Take a moment and try to describe the smell of fresh coffee. You might say it smells “like coffee,” or perhaps you’ll reach for metaphors: “rich,” “earthy,” “roasted,” “a warm hug in a mug.” Now, try to describe the color red without using the word “red” or comparing it to an object. It’s almost impossible. But for color, we don’t have to. We have “red,” “crimson,” “scarlet,” “vermilion.” For smell, our vocabulary often feels borrowed, imprecise, and frustratingly secondhand.

This chasm between our powerful sense of smell and our limited ability to name its sensations is known as the “olfactory-verbal gap.” While our languages are rich with thousands of words for colors, sounds, and shapes, our olfactory lexicon is notoriously impoverished. Why is it that a sense so deeply connected to memory and emotion leaves us so utterly speechless? The answer lies in a fascinating intersection of brain wiring, linguistic evolution, and cultural priority.

A Tale of Two Brain Pathways

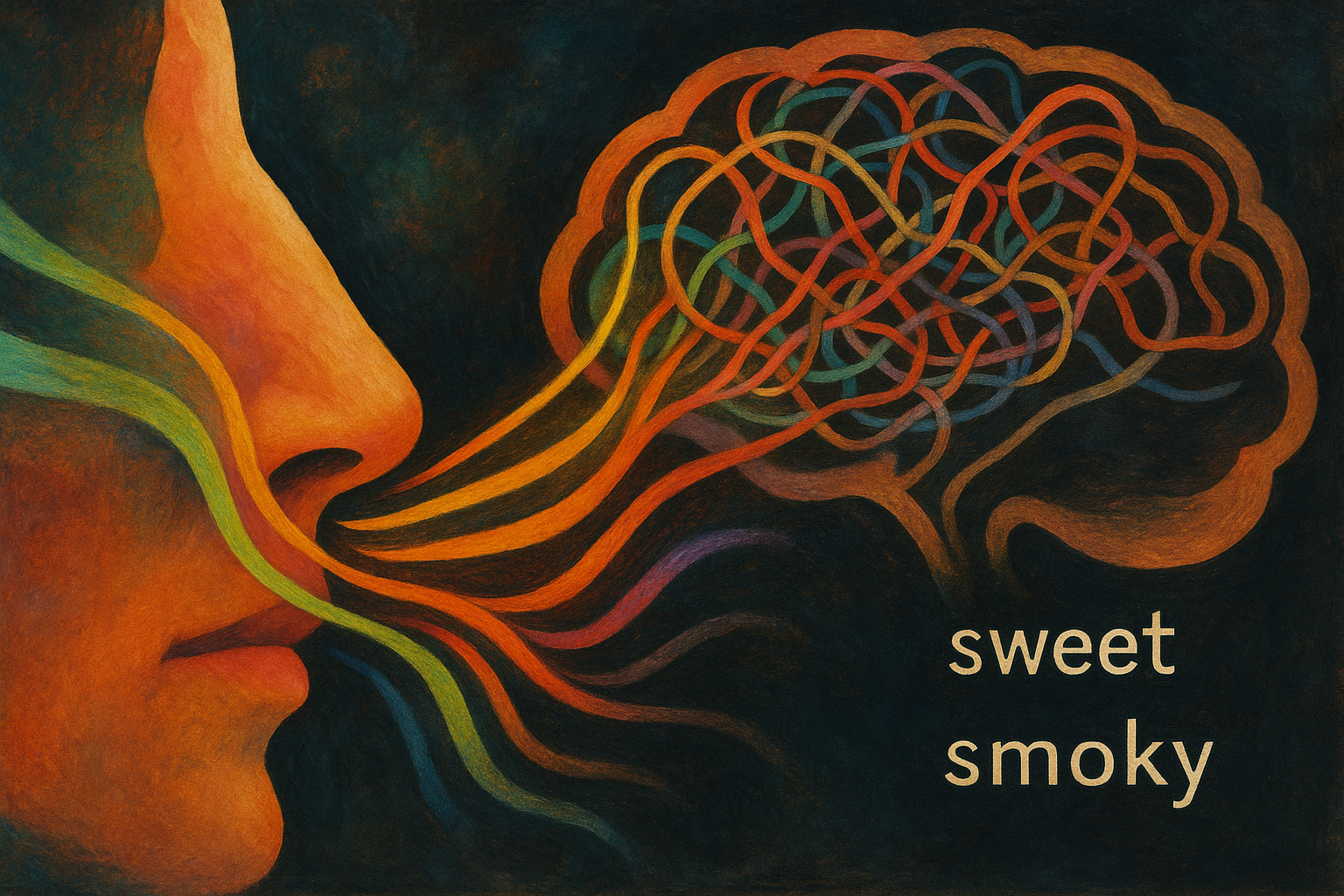

The primary reason for our verbal clumsiness with scent is neurological. When you see an object or hear a sound, that sensory information makes a crucial pit stop. It travels to the thalamus, the brain’s busy relay station, which then routes it to the relevant cortical areas, including the brain’s language centers (like Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas). This creates a well-established connection between perception and description.

Smell, however, takes a different route. As one of our most ancient senses, the olfactory bulb has a direct, privileged connection to the limbic system—the primitive part of our brain that governs emotion and memory. Specifically, it plugs straight into the amygdala (the emotion processor) and the hippocampus (the memory architect). This is why a whiff of a certain perfume can instantly transport you back to your grandmother’s house, or the smell of rain on hot asphalt can trigger a wave of nostalgia.

Smell takes the express highway to emotion and memory, bypassing the main linguistic processing hubs that other senses report to. It’s a deeply personal, internal experience before it’s an external, describable one. Our brain prioritizes feeling the smell over naming it.

The Vocabulary of Vapors: Why English Lacks Scent Words

This neurological bias is reflected in the structure of many languages, especially Western ones like English. Our vocabulary for odors falls into two main categories:

- Source-based descriptors: We describe a smell by what it comes from. Something smells “lemony,” “woody,” “floral,” or “like gasoline.” We are not describing the scent itself, but its origin.

- Evaluative descriptors: We describe our reaction to the smell. It is “fragrant,” “aromatic,” “pungent,” “acrid,” “foul,” or “stinky.” These words tell you if the smell is pleasant or unpleasant, but give very little information about its actual character.

What’s missing are abstract smell words. We have primary colors—red, yellow, blue—that are fundamental concepts. We don’t have primary smells. There is no word for the quality of “citrusness” that is independent of a lemon or an orange. Perfumers and sommeliers have tried to build frameworks like the “fragrance wheel” (dividing scents into families like Floral, Oriental, Woody, and Fresh), but even these are ultimately anchored in source-based categories.

Whispers on the Wind: Lessons from Olfactory Cultures

For a long time, this olfactory-verbal gap was considered a universal human trait. But recent linguistic research has shown this is a culturally specific problem, not a biological certainty. In some cultures, smell is not just an accessory sense—it’s a vital tool for survival, and their languages reflect this.

Linguist Asifa Majid has done groundbreaking work with the Jahai people, a hunter-gatherer group in the Malay Peninsula. The Jahai have a rich and nuanced vocabulary of abstract words for smell, on par with our words for color. For example:

- Cŋɛs describes the specific, piercing smell of gasoline, smoke, and certain insects.

- Plʔɛŋ refers to the bloody, fishy, or raw-meaty smell that attracts tigers.

- Pəŋih is a desirable, fragrant smell associated with some flowers, cooked foods, and bearcats (binturongs), which are used to perfume homes.

These are not comparisons; they are primary descriptors. For the Jahai, who navigate a dense rainforest environment, being able to precisely identify and communicate smells is critical for finding food, avoiding predators, and using medicinal plants. Similarly, the Manídeo of Brazil and other indigenous groups have demonstrated a sophisticated olfactory language born from necessity.

This tells us something profound: our language evolves to encode what is important to our culture. In many Western, urbanized societies, we have outsourced our survival to supermarkets and technology, diminishing the daily importance of our sense of smell. Our language, in turn, has let its olfactory muscles atrophy.

Can We Build a True Grammar of Scent?

If culture shapes our smell language, can we consciously improve it? This is exactly what specialists like wine sommeliers, coffee roasters, and perfumers do. They undergo rigorous training to develop a shared, precise lexicon to communicate about their craft.

A sommelier might describe a wine as having “notes of cassis, graphite, and damp forest floor.” A coffee expert might detect “hints of stone fruit, cocoa, and a jasmine-like finish.” While still heavily reliant on source-based analogy, this is a far more sophisticated system than most of us possess. They are, in effect, creating a specialized dialect for scent.

However, building a universal grammar of scent remains a monumental challenge. Unlike light or sound, which can be broken down into measurable wavelengths and frequencies, a single smell is often composed of hundreds of different volatile molecules in complex combinations. Furthermore, our perception of these molecules is notoriously subjective, shaped by our genetics and our unique library of memories.

Perhaps the final answer is that we can never describe smells with the objective precision of sight. But the effort to do so is a worthy one. The struggle to find the words forces us to pay closer attention, to connect with our memories, and to engage in the poetic act of metaphor. The syntax of scent may not be found in a dictionary, but in the rich, evocative, and deeply personal stories our noses tell our brains.