What do the English word two, the Latin duo, the Russian dva, and the Sanskrit dvá have in common? On the surface, they’re just words for the same number in different languages. But look closer. The core sound—a “d” followed by a “w” or “v” sound—is unmistakably present in all of them. This is no coincidence. It’s a clue, a linguistic breadcrumb trail leading back thousands of years to a single, common source.

This source is a language that no one has heard spoken for over 5,000 years. It was never written down, and it left behind no monuments. We call it Proto-Indo-European (PIE), and it is the great-great-great-grandparent of an astonishing number of modern and ancient languages, from Icelandic in the west to Bengali in the east. The story of how linguists brought this ghost language back to life is one of history’s greatest detective stories.

The Detective’s Toolkit: The Comparative Method

How do you reconstruct something you’ve never seen or heard? The primary tool is the comparative method, a rigorous process for comparing languages to determine their historical relationship. The method works because languages don’t change randomly; they change in regular, predictable ways.

Think of it like genetics. You and your cousins share features because you share grandparents. By comparing your features, a geneticist could make a pretty good guess about what your grandparents looked like. Linguists do the same thing with “daughter” languages to reconstruct the “parent” language.

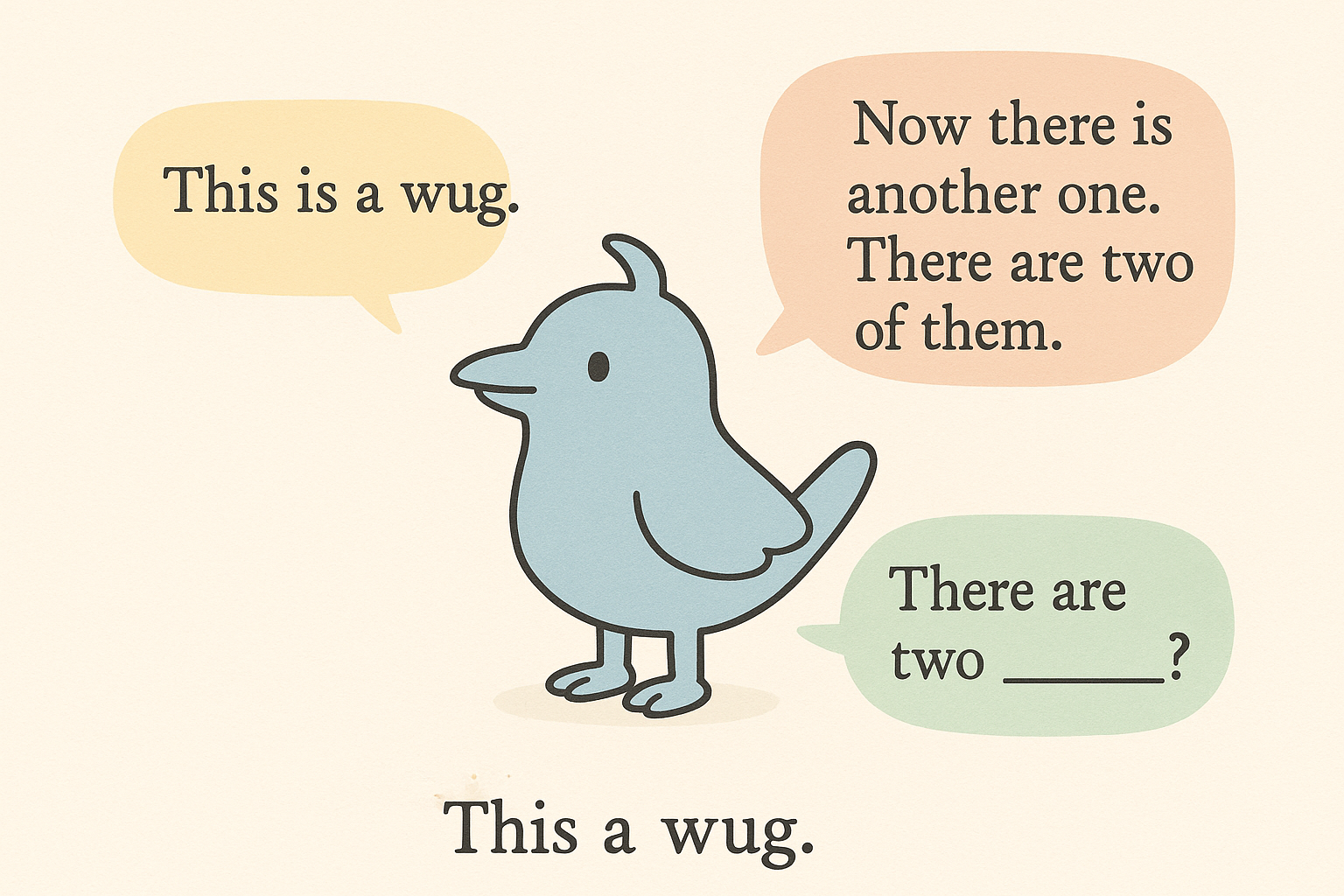

Step 1: Find the Family Resemblance (Cognates)

The first step is to identify cognates: words in different languages that have a common origin. These aren’t just words that sound similar because one language borrowed from another (like the English sushi from Japanese). Cognates are words that have been passed down from the shared parent language, slowly changing over millennia. A classic example is the word for “father”:

- Sanskrit: pitṛ́

- Ancient Greek: patḗr

- Latin: pater

- Gothic (an extinct Germanic language): fadar

- Old English: fæder (which became our modern father)

Step 2: Decode the Sound Changes

Once you have a set of cognates, you can establish sound correspondences. Notice how the Indo-Iranian (Sanskrit) and Italic (Latin) branches have a ‘p’ sound, while the Germanic branches (Gothic, English) have an ‘f’ sound. This isn’t a fluke; it’s a systematic shift. A famous rule called Grimm’s Law describes how certain consonants in the Germanic languages shifted away from their original PIE form. The original ‘p’ sound consistently became an ‘f’ in Germanic languages.

Step 3: Reconstruct the Ancestor

By working backward from these systematic changes, linguists can reconstruct the original word. Since the ‘p’ sound is present in the oldest and most geographically diverse branches of the family, it’s considered more original than the ‘f’ sound, which is a specific Germanic innovation. Therefore, linguists reconstruct the PIE word for “father” as *ph₂tḗr.

That asterisk (*) is crucial. It’s a scholarly convention indicating that the word is not attested—no one ever found it written down. It is a scientific reconstruction, a hypothesis based on overwhelming evidence from its descendants.

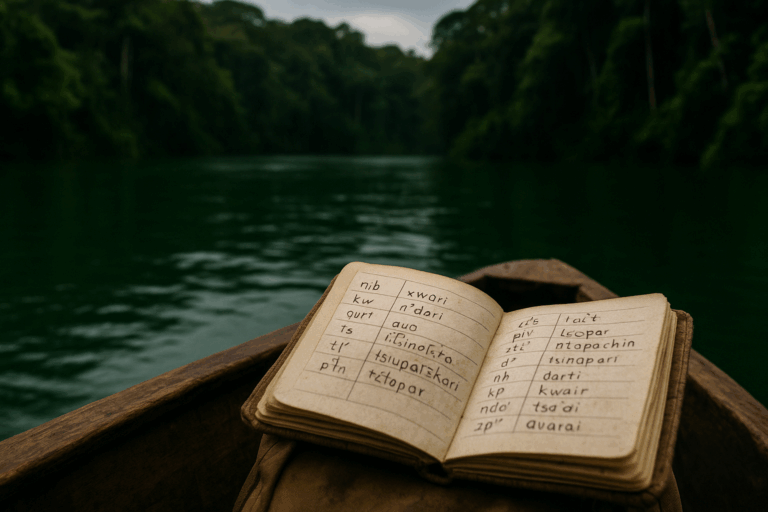

A Glimpse into a Lost Lexicon

Using the comparative method on thousands of words across hundreds of languages, linguists have pieced together a substantial PIE vocabulary. These reconstructed words are our only link to the minds of their speakers. The strange-looking characters represent specific sounds that may not exist in modern English but can be reconstructed with confidence.

- *wódr̥: The ancestor of English water, German Wasser, Russian voda, and Greek húdōr (as in hydro-).

- *gʷṓws: The ancestor of English cow, German Kuh, and Latin bōs.

- *nókʷts: The ancestor of English night, German Nacht, Latin nox, and Russian noch’.

- *dóru: This word meant “tree” or “wood.” It’s the ancestor of the English word tree, Russian dérevo, and the Greek word dendron (as in rhododendron).

- *h₃rḗǵs: Meaning “ruler” or “king.” This root gives us the Latin rēx (king), the Sanskrit rājan (ruler, as in maharaja), and via Celtic, the German Reich and English –ric in names like Frederick.

Rebuilding a World from Words

This reconstructed lexicon is more than just a word list; it’s an archaeological dig into a culture. The words a people use reveal the world they inhabit—what they see, what they value, and how they live. By analyzing the PIE vocabulary, we can paint a surprisingly detailed picture of this prehistoric society.

Their Environment and Homeland

The PIE speakers had words for snow (*sneygʷʰs), winter, wolves (*wĺ̥kʷos), and bears, but no native, common word for “ocean” or for animals like lions, elephants, or camels. This evidence strongly suggests a temperate, inland climate, far from the sea or tropical regions. This linguistic evidence, combined with archaeology, points to the Pontic-Caspian Steppe (modern-day Ukraine and southern Russia) as the most likely PIE homeland, or Urheimat, around 3500-2500 BCE.

Their Technology and Society

We know they were not simple hunter-gatherers. They had a sophisticated vocabulary for family and kinship, including words for mother (*méh₂tēr), father (*ph₂tḗr), brother, and sister. Their society was likely patrilineal (tracing descent through the father’s line).

Crucially, they had wheeled vehicles. Words for wheel (*kʷékʷlos, the source of “cycle”), axle, and wagon (*wéǵʰnos, the source of “wagon” and “vehicle”) are found across the language family. They domesticated animals, including cows, sheep (*h₃ówis), pigs, and, most importantly, the horse (*h₁éḱwos), which they used for transport and warfare, giving them a massive advantage as they expanded.

Their Beliefs

Perhaps most fascinating is the window into their religion. They worshipped a sky-father god, reconstructed as *Dyḗws Ph₂tḗr. Does that name sound familiar? It should. In India, he became the Vedic god Dyaus Pitṛ́. In Greece, he became Zeus Patēr. And in Rome, he became Iuppiter (Jupiter). The name of the chief god in three of the most influential ancient pantheons comes directly from a single, prehistoric source.

The story of Proto-Indo-European is a testament to the power of scientific inquiry to illuminate the distant past. It’s a reminder that beneath the surface of our diverse languages lies a hidden, shared history. The next time you mention the “night” or count to “two,” take a moment to appreciate the sound. You are not just speaking English; you are echoing a voice that has traveled through more than five millennia to reach you.