Think about the last casual chat you had. Maybe it was over coffee with a friend, a quick call with a family member, or a brainstorming session with a colleague. It probably felt effortless, a smooth back-and-forth of ideas and pleasantries. But what if I told you that in that simple exchange, you were participating in one of the most complex, high-speed, and finely tuned social rituals known to humanity?

How did you know when your friend was finished speaking? How did you signal that you wanted to jump in? How did you both manage to (mostly) avoid talking over each other? You weren’t following a script, yet the conversation flowed. This is the magic that fascinates linguists in the field of Conversation Analysis (CA). They look past what we say and zoom in on how we say it, revealing an intricate, unspoken rulebook that governs our every interaction.

The Science of “Um”: What is Conversation Analysis?

Born in the 1960s from the work of sociologist Harvey Sacks and his colleagues Emanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson, Conversation Analysis is a unique approach to studying human interaction. Unlike other areas of linguistics that might focus on abstract grammar or sentence structure, CA treats conversation as a structured, orderly activity in its own right.

CA practitioners work with real-world recordings of conversations—not staged dialogues, but the messy, authentic talk of everyday life. To them, the “mess” is where the data is. The hesitations, the “ums” and “ahs,” the false starts, the overlaps, and the pauses aren’t just noise to be filtered out. They are crucial signals, the very tools we use to manage our conversations. An “um” isn’t just a sign of thinking; it’s a strategic move to hold the conversational floor while you formulate your next thought.

The core belief of CA is that by meticulously analyzing these micro-details, we can uncover the underlying machinery of social order. We can see how people build shared understanding, negotiate relationships, and perform social actions—like inviting, complaining, or apologizing—all through the structure of their talk.

The Building Blocks of Talk: Turn-Constructional Units (TCUs)

To understand how we take turns, we first need to know what a “turn” is made of. In CA, the fundamental building block is the Turn-Constructional Unit (TCU). A TCU is a chunk of speech that can be recognized by a listener as a potentially complete utterance. It’s a complete thought, grammatically and intonationally.

A TCU can be:

- A single word: “Hello?”

- A phrase: “On the table.”

- A full clause: “I’m going to the store after work.”

As someone is speaking, listeners are constantly monitoring their speech, anticipating when the current TCU will end. This point of potential completion is the crucial moment where the conversational baton can be passed. And this moment has a name.

The Rules of the Game: The Transition Relevance Place (TRP)

The end of a TCU is called a Transition Relevance Place (TRP). It’s the spot where a change of speaker becomes relevant—and possible. It’s the “go” signal in the conversational race. Sacks and his colleagues observed that at every TRP, a remarkably consistent set of rules seems to apply, guiding who gets to speak next. These aren’t rules you’re consciously aware of, but you follow them with incredible precision.

Here’s a simplified version of the system:

- The Current Speaker Selects the Next Speaker: The person currently talking can nominate the next speaker, often by asking a direct question or using a name. For example, “I thought the movie was a bit slow, what did you think, Maria?” Here, Maria is given the explicit right to the next turn.

- The Next Speaker Self-Selects: If the current speaker doesn’t nominate anyone (Rule 1 isn’t used), any other participant can start talking. The first one to start claims the floor. This is the most common way turns are exchanged in multi-party conversations. It’s a free-for-all, but a surprisingly orderly one.

- The Current Speaker Continues: If no one else self-selects (Rule 2 doesn’t happen), the original speaker has the right to continue talking by adding another TCU. This is how someone can hold the floor to tell a longer story, linking multiple TCUs together.

This system is brilliantly economical. It minimizes both gaps (awkward silences) and overlaps (people talking at once) and ensures the conversation keeps moving forward. The vast majority of transitions from one speaker to the next happen with less than a 200-millisecond gap—faster than human reaction time, which proves we are predicting the TRP, not just reacting to it.

Signaling the End (and the Beginning): The Art of the Handoff

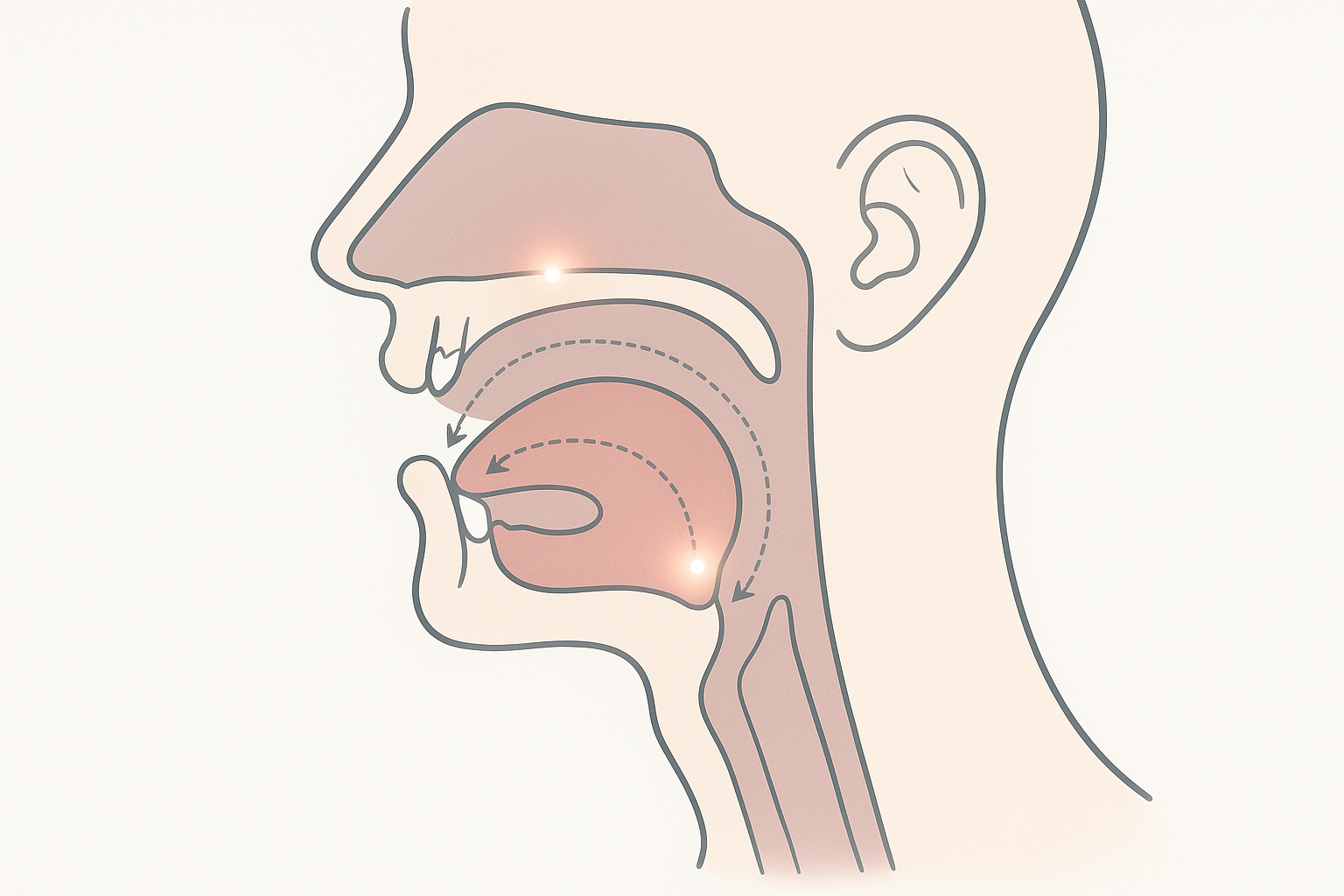

So, if we’re predicting the end of a turn, how do we do it? We rely on a rich cocktail of verbal and non-verbal cues that signal an approaching TRP.

- Intonation: The pitch of our voice is a powerful cue. A falling, declarative tone at the end of a statement (“I’m going home.“) or a rising, questioning tone (“Are you coming with me?“) signals a completed thought.

- Grammar: The completion of a grammatical clause is a strong indicator that a TCU is finished.

- Pauses: A tiny, well-placed pause at a grammatically appropriate point is a clear signal. But if the pause goes on for too long, it becomes an “attributable silence”—a silence that belongs to the person who was expected to speak. It’s no longer just a gap; it’s a meaningful communicative act in itself.

- Non-Verbal Cues: In face-to-face conversation, gaze is critical. A speaker might end their turn by looking directly at the person they expect to speak next, effectively passing the conversational torch with their eyes.

Fixing the Glitches: The Beauty of “Repair”

Of course, this system isn’t perfect. We mishear, we misspeak, we get interrupted. CA has a special interest in how we fix these problems, a process called repair. Repair is the mechanism we use to deal with any kind of trouble in speaking, hearing, or understanding.

Consider this exchange:

Alex: I’m meeting him at ten.

Ben: At ten in the morning?

Alex: No, ten at night.

Here, Ben initiates a repair (“other-initiated”) to clarify an ambiguity. Alex then performs the repair (“self-repair”). This constant, collaborative effort to fix conversational breakdowns shows just how invested we are in maintaining mutual understanding. The most common type of repair is when we fix our own mistakes as we’re speaking: “I went to the… uh, the library.” That “uh” is part of a self-initiated self-repair, buying a moment to correct the course.

The Unconscious Dance

The next time you find yourself in a conversation, take a moment to appreciate the invisible framework holding it all together. That seamless flow is not an accident. It is a highly coordinated linguistic dance, choreographed by a set of rules you learned without ever being taught and perform without ever thinking about it.

From the precise timing of your turn to the subtle intonation that signals you’re done, you are engaging in a system of breathtaking complexity. Conversation Analysis pulls back the curtain on this everyday miracle, showing us that even the most mundane chat is a masterpiece of social cooperation, built one turn at a time.