Imagine tracing your family tree. You find parents, grandparents, cousins, and distant ancestors, all connected by a shared lineage. Most of the world’s languages can do the same. English is a proud member of the Germanic family, a cousin to German and Dutch. Go back further, and it’s part of the vast Indo-European family, related to everything from Spanish and Russian to Hindi and Persian. But what if a language looked at its family tree and found… nothing? No parents, no cousins, no demonstrable relatives at all. Welcome to the fascinating, lonely world of language isolates.

A language isolate is a natural language with no proven “genetic” relationship to any other living or dead language. They are the orphans of the linguistic world. This doesn’t mean they exist in a vacuum—they still borrow words from their neighbors—but their core grammar, syntax, and fundamental vocabulary are entirely their own, having sprung from a source we can no longer trace.

What Makes a Language an “Isolate”?

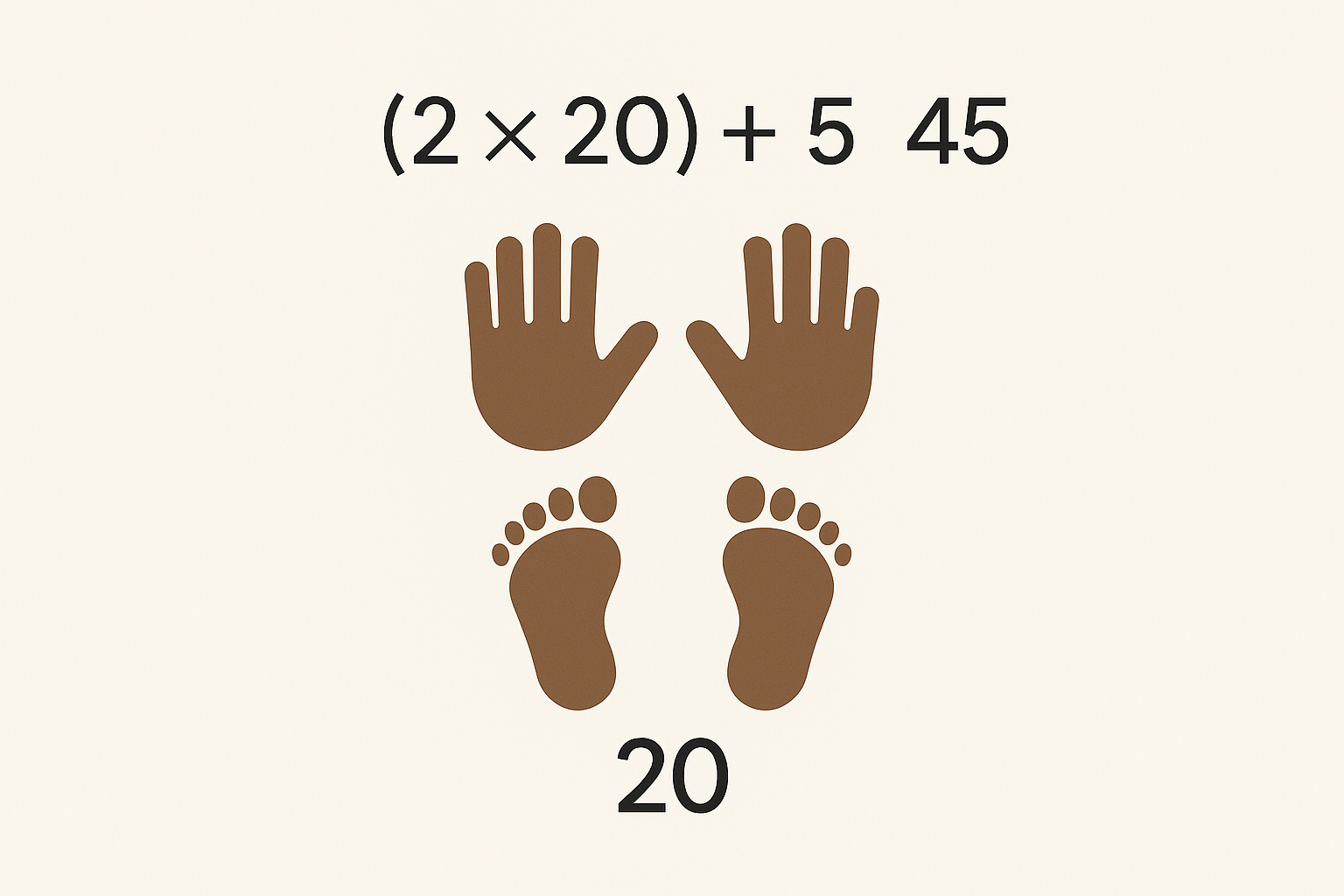

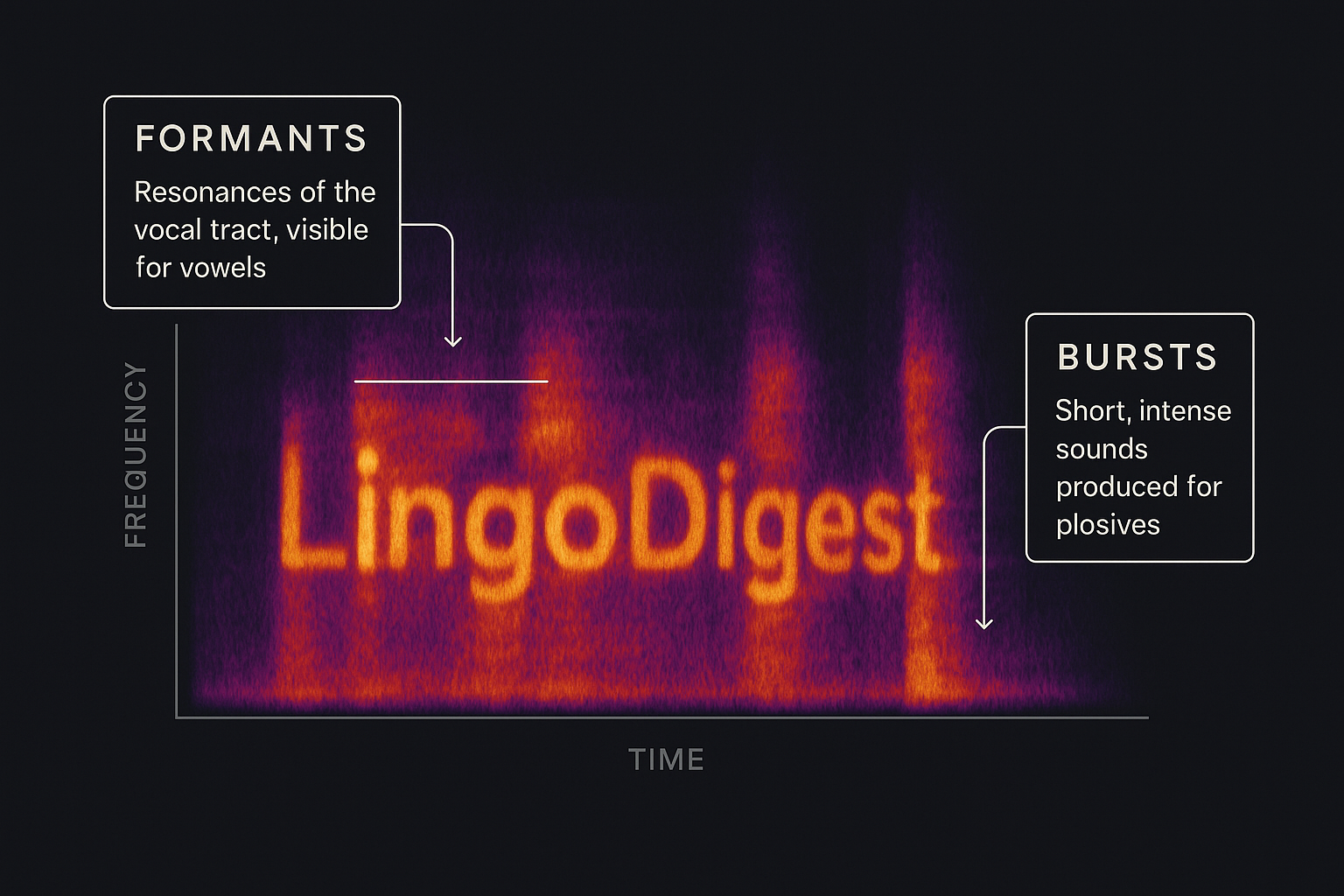

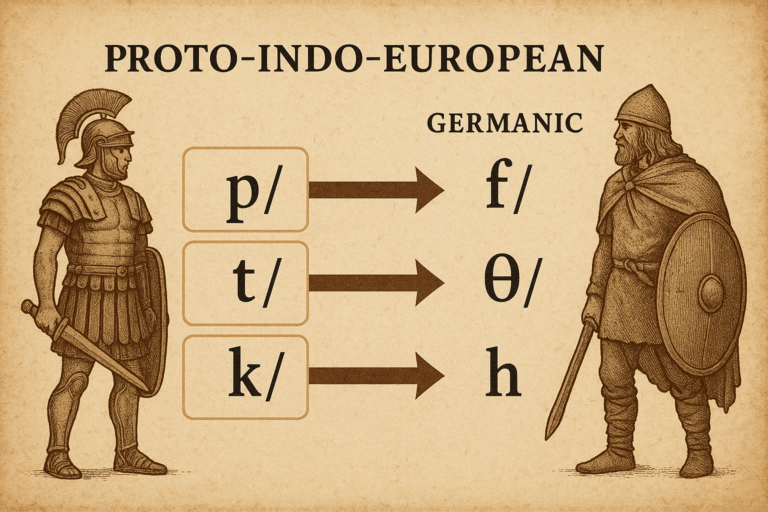

To understand what makes a language an isolate, we first have to understand how linguists build language families. Through a painstaking process called the comparative method, historical linguists compare the core vocabulary (words for body parts, family members, natural phenomena) and grammatical structures of different languages. They look for regular, systematic sound correspondences—for example, where an English word starts with ‘f’ (father, fish), its German cousin often starts with ‘v’ (Vater) and its Latin ancestor with ‘p’ (pater, piscis). When enough of these regularities pile up, a genetic relationship is proven.

A language isolate is simply a language where this process fails. Despite decades or even centuries of searching, linguists can find no consistent, systematic connections to any other language. An isolate isn’t just a language spoken in a remote location; it’s a language that represents a language family of one.

This isolation is often a matter of history. It’s highly probable that these languages once had relatives, but those relatives have all gone extinct, leaving our isolate as the sole survivor of a lost linguistic family.

A Tour of Linguistic Loneliness: Famous Isolates

The world is dotted with these unique linguistic treasures. While there are dozens of proposed isolates, a few stand out for their resilience, mystery, and the unique grammatical windows they open.

Basque (Euskara)

Perhaps the most famous isolate, Basque is spoken by the Basque people in the mountainous region spanning northeastern Spain and southwestern France. It is an island in a sea of Indo-European languages. While Spanish and French words have been borrowed over centuries, the fundamental structure of Basque is alien to its neighbors.

- Unique Feature: Ergativity. English, like most European languages, uses a nominative-accusative system. The subject of a sentence is always treated the same: “He runs” and “He hit the ball.” In Basque, the system is different. The subject of a sentence without a direct object (“The man runs”) is in the absolutive case. But in a sentence with a direct object (“The man hit the ball”), the subject (“the man”) is marked with a special ergative case, while the object (“the ball”) is in the absolutive case—the same as the subject of “The man runs”! This fundamentally different way of organizing grammar is a powerful reminder that our own linguistic “rules” are not universal.

Ainu

Spoken on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido by the indigenous Ainu people, Ainu is a critically endangered language with perhaps only a handful of native speakers left. It has no connection to Japanese or any other language family in Northeast Asia. Its origins are a complete mystery, with some scholars fruitlessly trying to link it to Siberian languages, others to languages of the Americas, and others still admitting defeat.

- Unique Feature: Polysynthesis. Ainu is a polysynthetic language, meaning it can build incredibly long and complex words that can contain the meaning of an entire English sentence. It does this by incorporating nouns and adverbs directly into the verb. While a simplified example, it captures the idea of creating a single “verb-word” like “I-story-tell-you” instead of a multi-word sentence. This intricate word-building showcases a completely different strategy for conveying information.

Sumerian

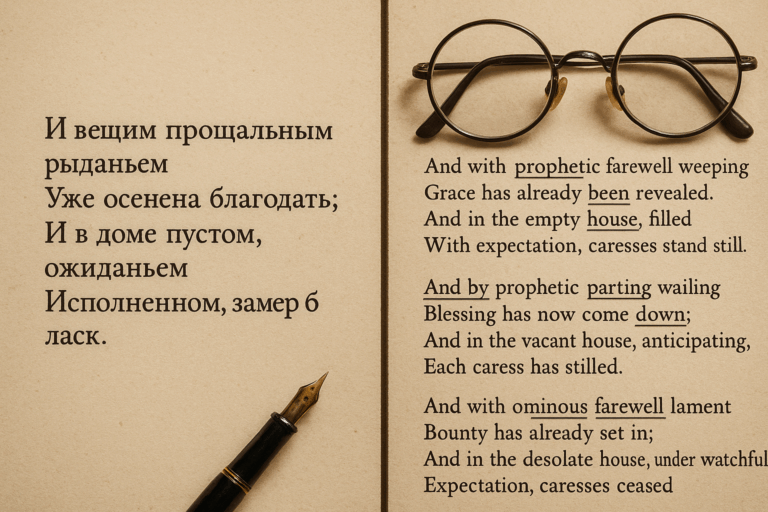

Jumping back 5,000 years, we find Sumerian, one of history’s first written languages. Preserved on clay tablets in cuneiform script, it was the language of ancient Sumer in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). Despite its incredible age and the wealth of texts we possess, Sumerian remains an isolate. Its neighbors and successors, like Akkadian (a Semitic language), were completely unrelated. The Sumerians seem to have appeared in the historical record with a fully formed, unique language, whose family, if it ever had one, is lost to prehistory.

- Unique Feature: Split Ergativity. Like Basque, Sumerian used an ergative system, but with a twist. It was “split” based on tense and aspect. In some grammatical contexts, it behaved like an ergative language, and in others, it behaved like the nominative-accusative languages we are more familiar with.

The Lost Families: How Does a Language Become Isolated?

Languages don’t just spring out of nowhere. The existence of isolates points to a history of immense linguistic loss. The leading theory is that isolates are the last survivors of ancient language families that have otherwise been wiped out.

Think of the spread of Indo-European languages across Europe. They likely displaced or assimilated dozens of pre-existing language families. Basque is theorized to be the only remaining descendant of one of these pre-Indo-European language groups. Similarly, the spread of Japonic languages through Japan likely pushed out other language families, leaving Ainu as a solitary remnant in the north.

War, disease, cultural assimilation, and demographic shifts can all lead to language death. When every language in a family dies out except for one, that lone survivor becomes an isolate.

Windows into the Mind: What Isolates Teach Us

Language isolates are more than just linguistic curiosities; they are invaluable to our understanding of human cognition. They are the ultimate test cases for theories about “Universal Grammar”—the idea that all human languages share a common, innate structural foundation.

Isolates demonstrate the incredible plasticity and creativity of the human mind. They show us that there are many different, equally valid ways to structure reality through language. Systems like ergativity, polysynthesis, and unique verb conjugations challenge our assumptions about what is “normal” or “logical” in communication.

Each isolate is a self-contained history book, a repository of a culture’s unique worldview. Its survival is a testament to the resilience of its speakers. But many, like Ainu, are on the brink of extinction. When an isolate dies, an entire branch of the human linguistic tree—a branch with no other offshoots—is pruned forever. The loss is absolute. Their study and preservation are a race against time to capture a singular facet of human expression before it vanishes.