Picture a friend telling you an exciting, convoluted story. They lean in, eyes wide, and their hands start to move. They might sketch the shape of a winding road in the air, chop their hand down to mark a sudden turn of events, or hold their palms far apart to emphasize the scale of the problem. You’re not just listening to their words; you’re watching a silent ballet that gives their story life, depth, and clarity. We all do this. We don’t just talk with our mouths; we talk with our hands.

This phenomenon, known as co-speech gesture, is one of the most fascinating and universal aspects of human communication. It’s not sign language, which is a fully formed linguistic system with its own grammar and vocabulary. Instead, these are the spontaneous, largely unconscious movements that are inextricably linked to the act of speaking. They are, in a sense, the hidden grammar of our thoughts, revealing how we organize ideas in real-time.

More Than Just Hand-Waving: The Integrated System

For a long time, gestures were seen as mere ornamentation—an expressive flourish that added a bit of dramatic flair but little else. However, pioneering researchers like David McNeill fundamentally changed this view. He proposed that speech and gesture are not two separate systems but two sides of the same coin. They erupt from the very same cognitive process, what he calls a “growth point”—the initial spark of a thought before it’s fully packaged into linguistic form.

Think about it: have you ever tried to explain a complex idea while sitting on your hands? It’s surprisingly difficult. This isn’t just because you feel constrained; it’s because you’ve disabled a critical tool your brain uses for thinking. These gestures aren’t planned. They flow in perfect synchrony with our words, often even slightly preceding the word they relate to, as if paving the way for it to emerge from our mouths.

A Taxonomy of Talk: The Four Main Types of Gestures

While they may seem random, linguists and psychologists have identified several distinct categories of co-speech gestures. Understanding them helps decode the unspoken layer of conversation.

- Iconic Gestures: These are probably the most intuitive. Iconic gestures physically resemble the object or action they describe. When you talk about a “spiraling staircase” and trace a spiral with your finger, or when you describe a “big, round ball” by cupping your hands, you’re using iconic gestures. They provide a direct visual analogue to your words.

- Metaphoric Gestures: This is where things get abstract. Metaphoric gestures give physical form to concepts that have no physical shape. If you say, “We need to put that idea behind us,” you might sweep your hand backward. Talking about “the future,” you might gesture forward. Presenting two opposing options, you might use your left and right hands to represent “on the one hand” and “on the other hand.” These gestures map abstract ideas onto physical space, making them easier to grasp.

- Deictic Gestures: Derived from the Greek word for “to show,” deictic gestures are simply acts of pointing. They can refer to physical objects or people in the immediate environment (“Can you pass me that book?”). But more interestingly, they can also point to abstract locations. In a narrative, a speaker might point to a spot to their left when referring to one character and a spot to their right for another, creating a consistent “stage” in the conversational space.

- Beat Gestures: These are the subtle conductors of our speech rhythm. A beat gesture is a small, repetitive flick of the hand or finger that doesn’t depict anything specific but instead marks the tempo and emphasizes certain words or phrases. They are like the metronome of our sentences, helping to structure the flow of information and signal what’s important. Think of a politician rhythmically tapping the podium to drive a point home.

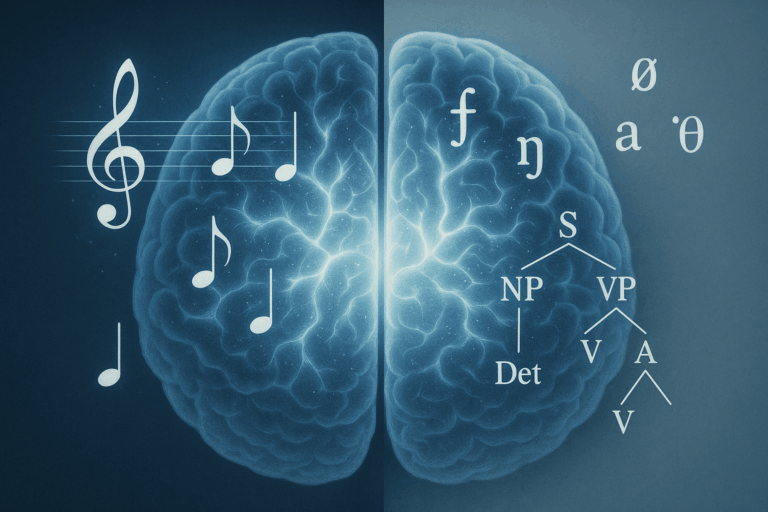

The Brain’s Duet: How Gestures Help Us Think and Speak

So, why do we gesture? The neuroscience behind it reveals a deep connection between our hands and our minds, serving both the speaker and the listener.

For the Speaker: Easing the Cognitive Load

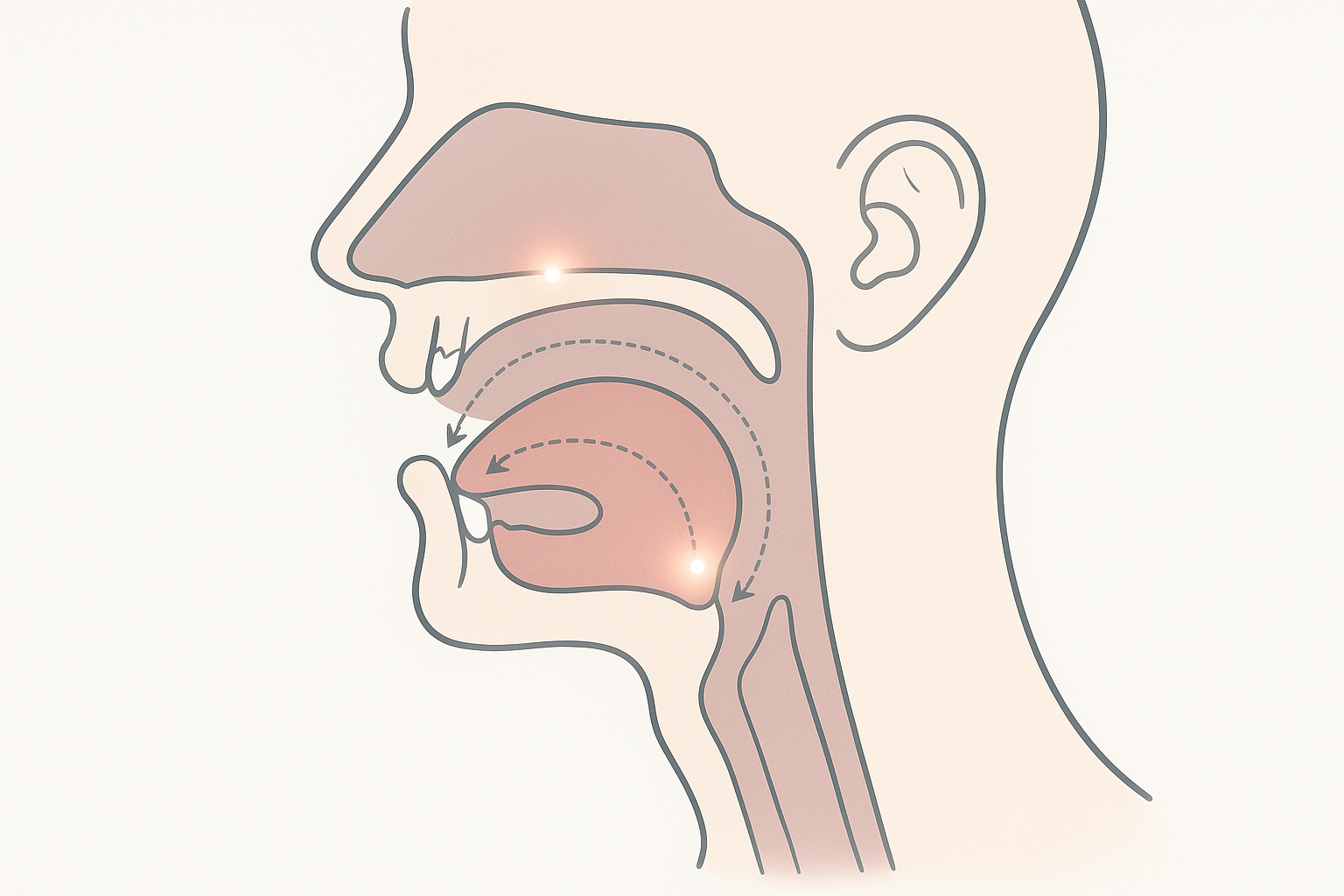

Speaking is hard work. Our brains are constantly searching for words, structuring sentences, and organizing complex thoughts. Gesturing helps to “offload” some of this cognitive burden. By representing spatial or metaphorical information physically, we free up mental resources to focus on finding the right words (a process called lexical retrieval).

Have you ever been on the tip of your tongue, unable to find a word? Studies show that people gesture more in these moments. It’s as if the hand is trying to “grasp” the elusive word. This makes sense neurologically: Broca’s area, a key region in the brain’s left hemisphere, is critical for both speech production and complex motor control of the hands. The two functions are neighbors in our neural architecture.

For the Listener: A Richer Message

For those on the receiving end, gestures are a gift. They provide a second, parallel channel of information that enriches and clarifies the spoken message. When a speaker’s iconic gesture illustrates the shape of an object, it enhances the listener’s mental imagery. When a metaphoric gesture grounds an abstract idea in space, it makes the concept less daunting.

Research has shown that listeners retain information significantly better when a speaker gestures. Gestures can also disambiguate. The phrase “he hit him with the bat” can be clarified instantly by a gesture indicating either a baseball bat or a flying mammal.

A Universal Language with Cultural Dialects

The impulse to gesture while speaking is a human universal. Even individuals who have been blind from birth gesture when they talk, including when speaking to other blind individuals who cannot see them. This proves that gesture is not just for the listener’s benefit; it’s fundamentally tied to the speaker’s own thought process.

However, while the types of gestures are universal, their form, frequency, and size—the “gesture space”—are shaped by culture. We are all familiar with the stereotype of the effusive Italian speaker, whose large, expressive gestures are an integral part of their communication style. In contrast, some East Asian cultures may favor more restrained and subtle movements.

Furthermore, some gestures, known as emblems, are culturally specific and have a direct verbal translation (e.g., the “thumbs-up” or “A-OK” sign). These are learned and conscious, unlike the co-speech gestures we’ve been exploring, and can lead to serious miscommunication across cultures. But the underlying, unconscious drive to sync our hands with our words is something we all share.

So the next time you’re in a conversation, pay attention—not just to the words, but to the dance of the hands. They aren’t just flailing about randomly. They are tracing the outlines of ideas, marking the rhythm of thought, and pointing the way through complex narratives. They are a testament to the fact that language is an embodied process, a beautiful duet performed by the mind and the body working in perfect harmony.