We leave traces of ourselves everywhere we go. A fingerprint on a glass, a footprint in the mud, a strand of hair on a jacket. But what about the traces we can’t see? The ones we create every time we send a text, write an email, or even speak a sentence aloud. These are our linguistic fingerprints, and for a special type of detective, they are as revealing as DNA. Welcome to the fascinating world of forensic linguistics, where your own words can, and often do, betray you.

The Language of a Crime Scene

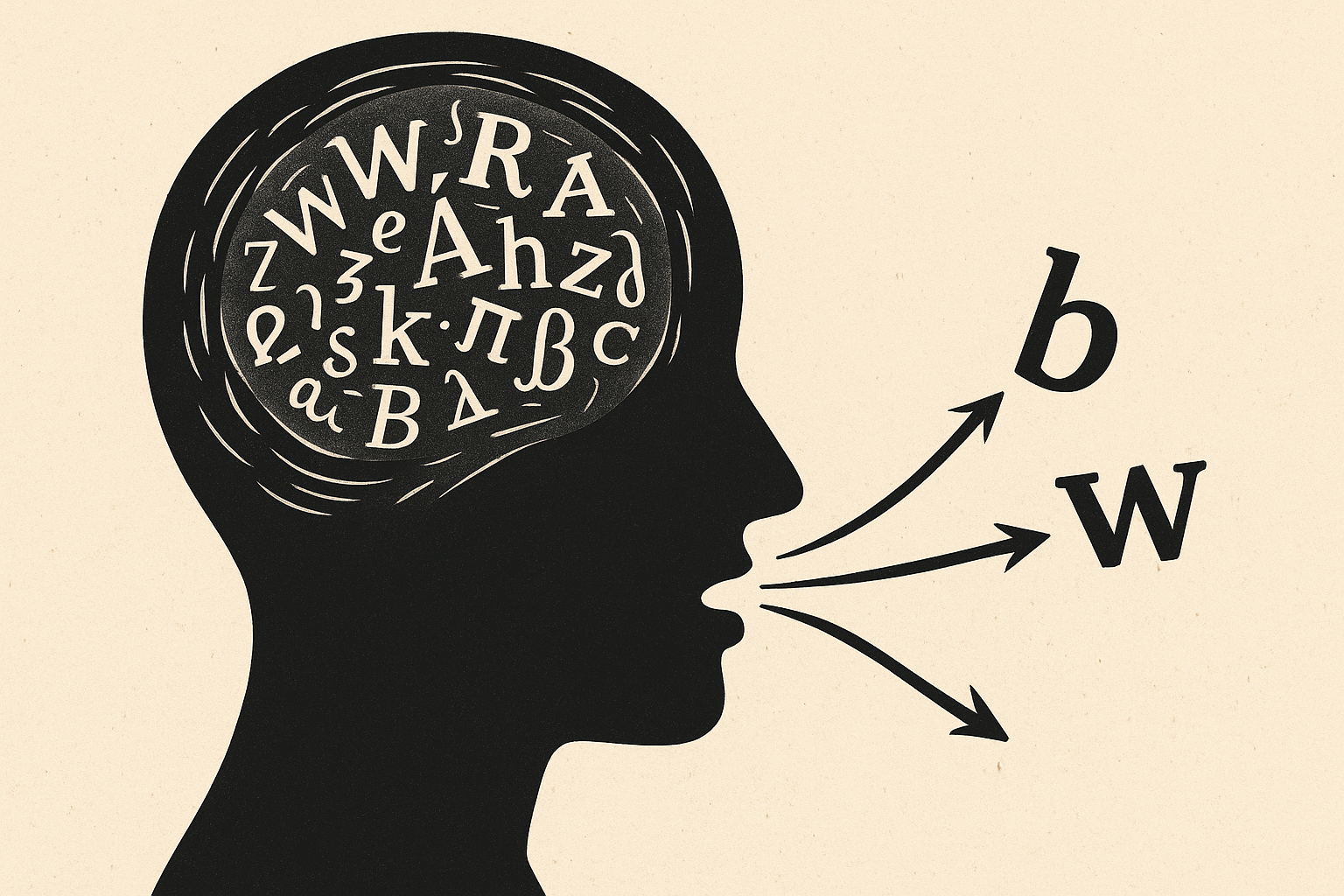

At its core, forensic linguistics is the application of linguistic science to legal matters. Experts in this field don’t just look at what is said, but how it’s said. They operate on a foundational principle: every individual has a unique and largely subconscious language profile, known as an idiolect. Think of it as your personal linguistic style.

Your idiolect is a cocktail of all your language habits, including:

- Vocabulary Choice: Do you say “soda,” “pop,” or “coke”? “Purse” or “handbag”?

- Spelling and Grammar: Are you prone to specific typos, like “seperate” for “separate”? Do you use the Oxford comma religiously?

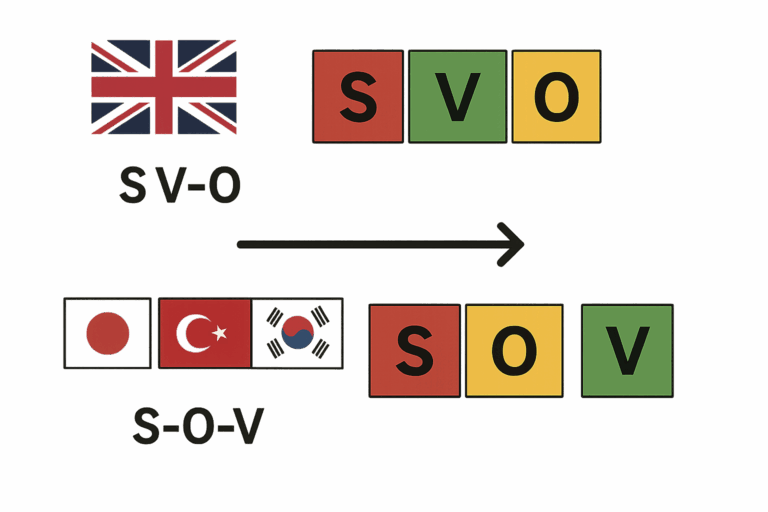

- Syntax: How do you structure your sentences? Are they long and complex, or short and direct?

- Punctuation: Do you use ellipses (…) frequently? Are you a fan of the em-dash?

- Discourse Markers: Do you start sentences with “Well,” or pepper your speech with “you know” or “like”?

When a criminal writes a ransom note, a threatening email, or a fraudulent post, they inadvertently embed their idiolect into the text. For a forensic linguist, this text is a crime scene, and these linguistic tics are the clues left behind.

In the Courtroom: Cases Cracked by Language

While the science is complex, its application is often stunningly direct. Linguistic evidence has been the linchpin in some of the most famous criminal cases in history, leading to both convictions and exonerations.

The Unabomber’s Manifesto

Perhaps the most celebrated case of forensic linguistics is that of Ted Kaczynski, the “Unabomber.” For 17 years, he eluded the FBI, his only communication being through letters and bombs. The breakthrough came in 1995 when he demanded that major newspapers publish his 35,000-word manifesto, “Industrial Society and Its Future.”

The FBI published it, hoping someone would recognize the author’s unique voice. The gamble paid off. David Kaczynski read the manifesto and was struck by its unnerving similarity to letters from his estranged brother, Ted. It wasn’t just the anti-technology ideology; it was the specific phrasing. Both the manifesto and Ted’s letters used idiosyncratic phrases like “cool-headed logician” and archaic constructions. FBI forensic linguist James R. Fitzgerald conducted a detailed comparison, confirming that the idiolects were a match. Ted Kaczynski’s own words led the FBI directly to his cabin door.

“Let Him Have It, Chris”

Forensic linguistics doesn’t just convict; it can also correct miscarriages of justice. In 1952, 19-year-old Derek Bentley was hanged for the murder of a police officer in London. Bentley, who had learning difficulties and a low IQ, was with his armed friend, Christopher Craig, during a botched robbery. When cornered by police, Bentley allegedly shouted, “Let him have it, Chris.” Craig then shot and killed an officer.

The prosecution argued this phrase was a clear command to shoot. Decades later, linguists re-examined the case. They analyzed Bentley’s police confession and found it was linguistically impossible for him to have authored it. The vocabulary, grammar, and sentence structure were far beyond his documented abilities, suggesting it was heavily coached or fabricated by police. Furthermore, they argued the phrase “Let him have it” was ambiguous. In the context of the era and slang, it was just as likely—if not more so—to have meant “Give him the gun.” This linguistic analysis was crucial in securing Bentley a posthumous pardon in 1993 and overturning his conviction in 1998.

The Digital Age: Texts, Tweets, and Deception

Today’s criminals have traded ransom notes for text messages and manifestos for social media rants, but the principles of forensic linguistics remain the same. The field has evolved to analyze the unique markers of digital communication.

Linguists now study:

- Textspeak and Emojis: The consistent use (or misuse) of emojis, abbreviations (like “lol” vs. “LOL”), and punctuation in texts can help establish authorship. In the infamous case of Michelle Carter, her text messages encouraging her boyfriend Conrad Roy to commit suicide were the central evidence leading to her involuntary manslaughter conviction. The analysis of tone, persuasion, and intent within those texts was a form of forensic discourse analysis.

- Social Media Profiles: When a suspect denies writing an incriminating social media post, linguists can compare its style to their other known posts, looking for consistencies in hashtag use, phrasing, and even meme choices.

- Statement Analysis: Beyond authorship, linguists analyze the structure of statements to detect deception. For example, a genuine emergency call often has a different narrative structure than a staged one. A truthful narrator might speak in a confused, non-linear way, while a deceptive person often tells a story that is “too perfect”—chronologically ordered and free of natural digressions.

Your Words Are Your Signature

The world of forensic linguistics is a powerful reminder that language is more than just a tool for communication; it is a fundamental part of our identity. It’s a habit, a reflex, a collection of quirks built over a lifetime. While most of us will never have our words scrutinized in a courtroom, the principle holds true for everyone. From the way you sign off an email to the slang you use with friends, you are constantly creating a linguistic trail.

So the next time you write, remember the invisible signature you’re leaving behind. For in the intricate patterns of our prose and the unconscious rhythms of our speech, there lies a truth that is incredibly difficult to fake—a truth that, for some, can be the difference between freedom and conviction.