Dialect coaching is a fascinating intersection of art and science. It’s a field dedicated to deconstructing the very fabric of speech—its sounds, its music, its physical production—and rebuilding it within an actor’s performance. It’s about teaching someone not just to imitate an accent, but to embody a new way of speaking from the inside out.

More Than Just an Ear for Accents

Many people can “do” an accent, but it often borders on caricature. A true dialect performance feels lived-in, authentic, and specific to the character. This is the dialect coach’s primary goal: to move an actor from superficial imitation to genuine embodiment. They aren’t just teaching a generic “Southern accent”; they’re teaching the specific sociolect of a 45-year-old lawyer from Savannah, Georgia, whose parents were from Appalachia.

To do this, a coach functions as a linguist, a vocal technician, and an acting coach all in one. They provide the actor with a blueprint of the dialect, breaking it down into manageable, learnable components.

Deconstructing Sound: The Phonological Blueprint

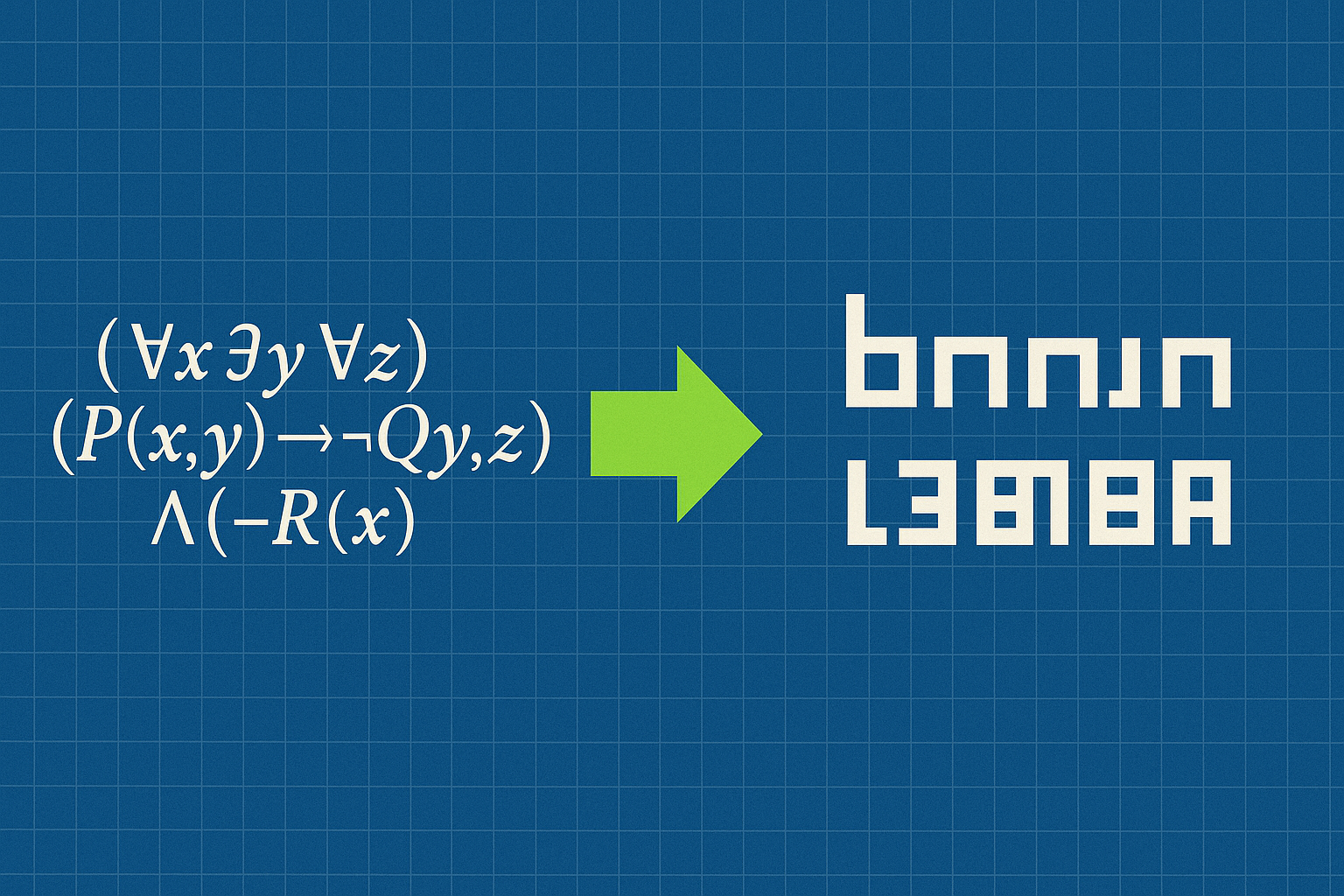

At the heart of any dialect are its unique sounds, or its phonology. A dialect coach begins by creating a phonological map, contrasting the actor’s native speech patterns with the target dialect. The primary tool for this is the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), a universal system where each symbol corresponds to a single, distinct sound, eliminating the ambiguities of standard spelling.

Vowels: The Heart of the Accent

Vowels are the soul of a dialect. They are produced by the shape of the mouth, and slight changes in tongue height and position create vastly different sounds. Coaches often focus on key vowel shifts:

- The “ah” vs. “a” sound: The vowel in “trap” is a classic differentiator. In many American accents, it’s a flat /æ/ sound. In a standard British accent (RP), the vowel in a word like “bath” shifts back to a broad “ah” /ɑː/.

- The “o” sound: A dialect coach for Mare of Easttown would have worked extensively with Kate Winslet on the Delaware County “o” sound. Words like “home” and “phone” don’t have the typical American /oʊ/ diphthong. Instead, the vowel is fronted and rounded, sounding more like “hewm” or “phewn” (/həʊm/). It’s a precise muscular adjustment that instantly signals locality.

Consonants: The Defining Edges

Consonants provide the structure and clarity of speech. A coach will identify key consonantal features that define a dialect:

- Rhoticity (The “R” sound): This is one of the most famous dividers. Is the “r” pronounced after vowels? In rhotic accents (like General American), the “r” in “park the car” is fully pronounced. In non-rhotic accents (like Boston, classic RP, or Australian), the “r” is dropped, resulting in “pahk the cah.”

- The “T” sound: What happens to the “t” in the middle of a word like “butter”? In RP, it’s a crisp /t/. In General American, it’s often a “tap” or “flap,” sounding like a soft “d” (/ɾ/). In Cockney or Estuary English, it’s frequently a glottal stop, where the vocal cords briefly close: “bu’er” /bʌʔə/.

- The “Th” sound: The “th” sounds (/θ/ as in “thin” and /ð/ as in “this”) are notoriously tricky. A coach might teach an actor playing a Cockney character to replace them with /f/ and /v/, respectively, turning “mother” into “muvver.”

The Music of Speech: Prosody and Intonation

An accent is more than a collection of sounds; it has its own melody. This is the realm of prosody—the rhythm, stress, and intonation of speech. A dialect coach helps an actor find the “music” of the dialect, which is often harder to master than individual vowels and consonants.

Rhythm refers to the timing of speech. English is a stress-timed language, meaning the rhythm is determined by the stressed syllables, while unstressed syllables are compressed. But the pattern varies. The staccato rhythm of a Welsh accent is very different from the legato, drawn-out rhythm of a deep Southern American drawl.

Intonation is the pitch contour, or the rising and falling of the voice. This is crucial for authenticity. For example:

- Australian Question Intonation (AQI): Even when making a statement, speakers often end with a rising pitch, making it sound like a question to outsiders.

- The Irish “Lilt”: This musical quality comes from a unique intonation pattern, where the pitch tends to rise and fall more frequently within a single sentence.

Mastering this music is what makes a dialect feel natural rather than robotic. It’s what connects the sounds to the culture and emotional landscape of the character.

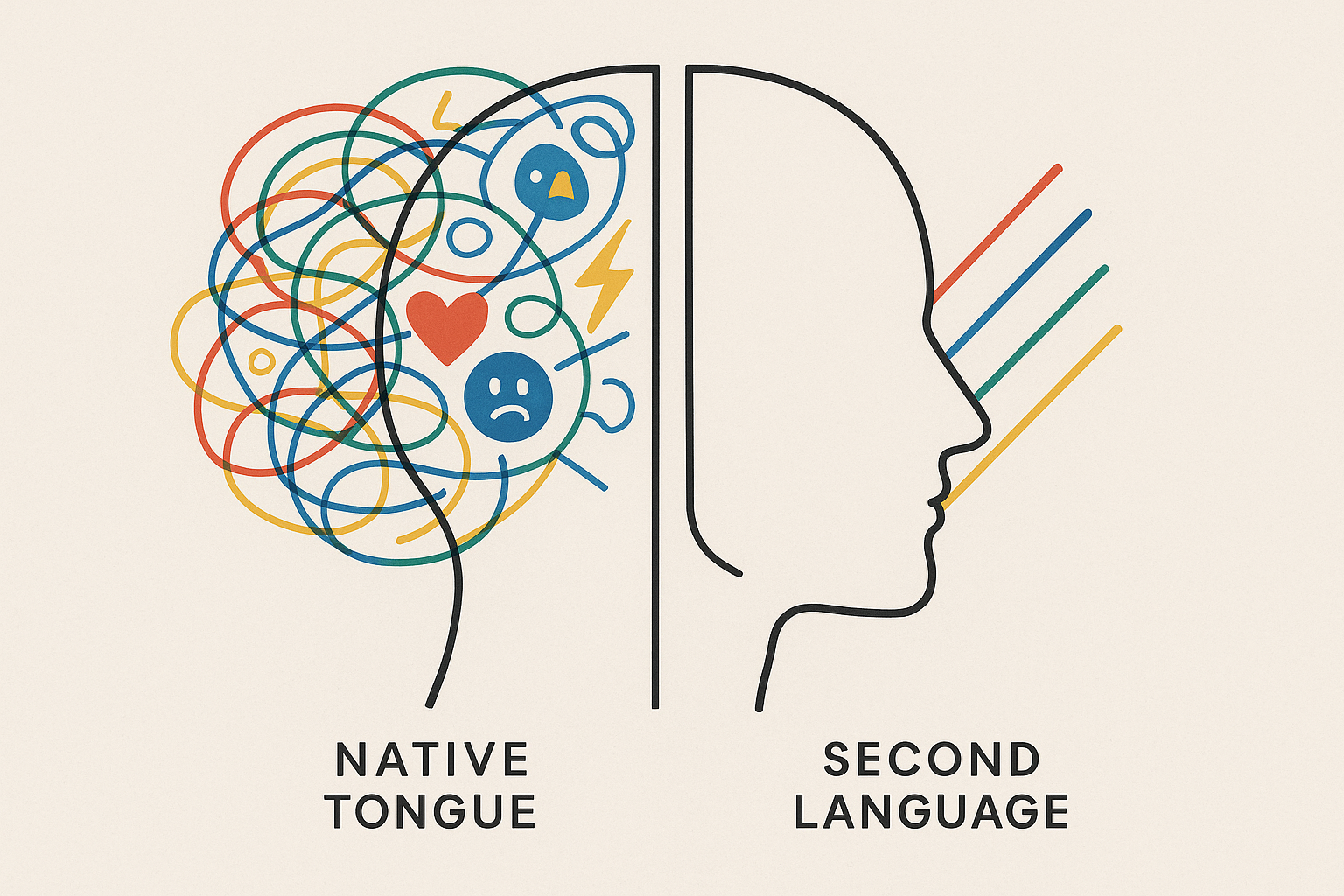

The Physicality of Speech: Articulatory Gymnastics

Every dialect has a physical center. Speaking is a muscular act, and our native dialect trains our tongue, jaw, and lips to move in specific, habitual ways. Learning a new dialect requires retraining this muscle memory.

A coach acts as a physical trainer for the mouth. They focus on placement, or where the sound seems to resonate.

- A classic RP British accent is often described as “forward,” with more muscularity and rounding in the lips.

- A General American accent is typically more relaxed and centered in the middle of the mouth.

- A French accent utilizes more nasal resonance, channeling air through the nose for certain vowels.

Coaches use physical exercises, stretches, and awareness techniques to help the actor find this new “home base” for their voice. It’s about feeling the dialect in the body, not just hearing it in the ear. The goal is for the muscular movements to become so second nature that the actor can focus on their performance without consciously thinking about, for example, the position of their tongue.

From Script to Screen

The process is collaborative and intensive. It begins with the coach and actor immersing themselves in authentic source recordings of real people from the target region. The coach then breaks down the script phonetically, line by line, identifying potential pitfalls. They work one-on-one, starting with individual sounds, then words, then phrases, gradually integrating the dialect into the text. Finally, the coach is often on set, listening through headphones during takes to give minor adjustments, ensuring consistency and accuracy under the pressure of filming.

The next time you watch a film and find yourself completely believing an actor’s transformation, take a moment to appreciate the invisible artist behind the performance. The dialect coach is the linguist in the wings, the architect of authenticity who proves that language isn’t just what we say, but who we are—and who we can become.