Picture a brand-new country, its borders finally drawn after a long and bloody struggle for unification. A flag flies over the capital, a king is on the throne, and a sense of national pride is in the air. There’s just one problem: almost nobody speaks the same language. This wasn’t a hypothetical scenario; this was the reality for Italy in 1861.

When the Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed, the politician Massimo d’Azeglio famously remarked, “L’Italia è fatta. Restano da fare gli italiani.” — “We have made Italy. Now we must make Italians.” A core part of that Herculean task was forging a single, unified voice. The story of how the modern Italian language was chosen, crafted, and spread across the peninsula is a fascinating tale of literature, politics, and the surprising power of the television set.

A Nation United, A Language Divided

In 1861, what we call “Italian” was the native tongue of a tiny fraction of the population—estimated to be as low as 2.5%. These speakers were mostly educated elites living in Tuscany and Rome. For everyone else, daily life was conducted in a vibrant tapestry of regional languages, often misleadingly called “dialects” (dialetti).

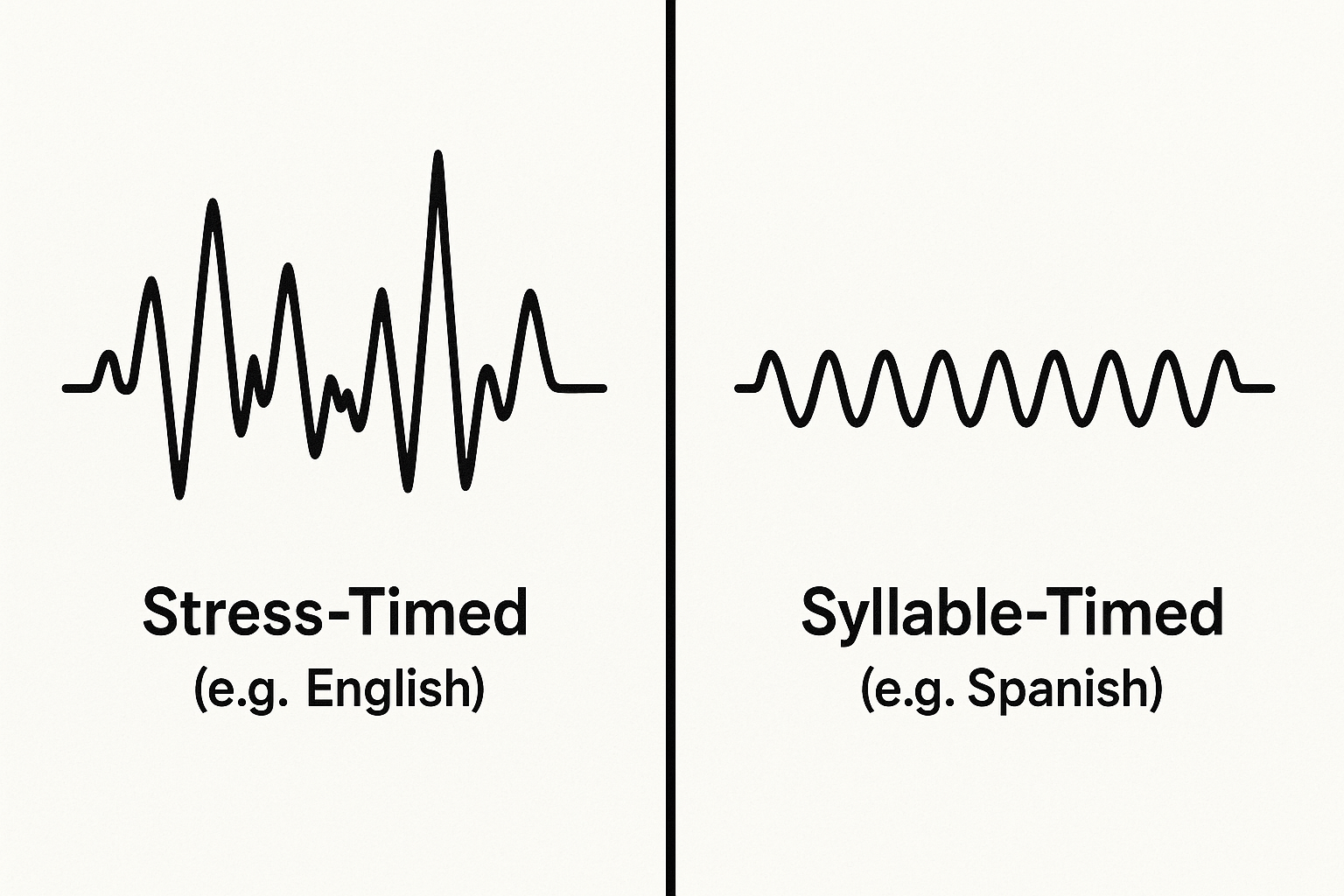

These weren’t just quirky accents. The languages of Sicily, Naples, Venice, and Piedmont were as different from each other as Spanish is from Portuguese. A farmer from the Veneto and a fisherman from Sicily would have found it nearly impossible to hold a conversation. The new Italian state faced a logistical and cultural crisis. How could you run a government, establish a national education system, or build a cohesive identity when your citizens couldn’t understand one another?

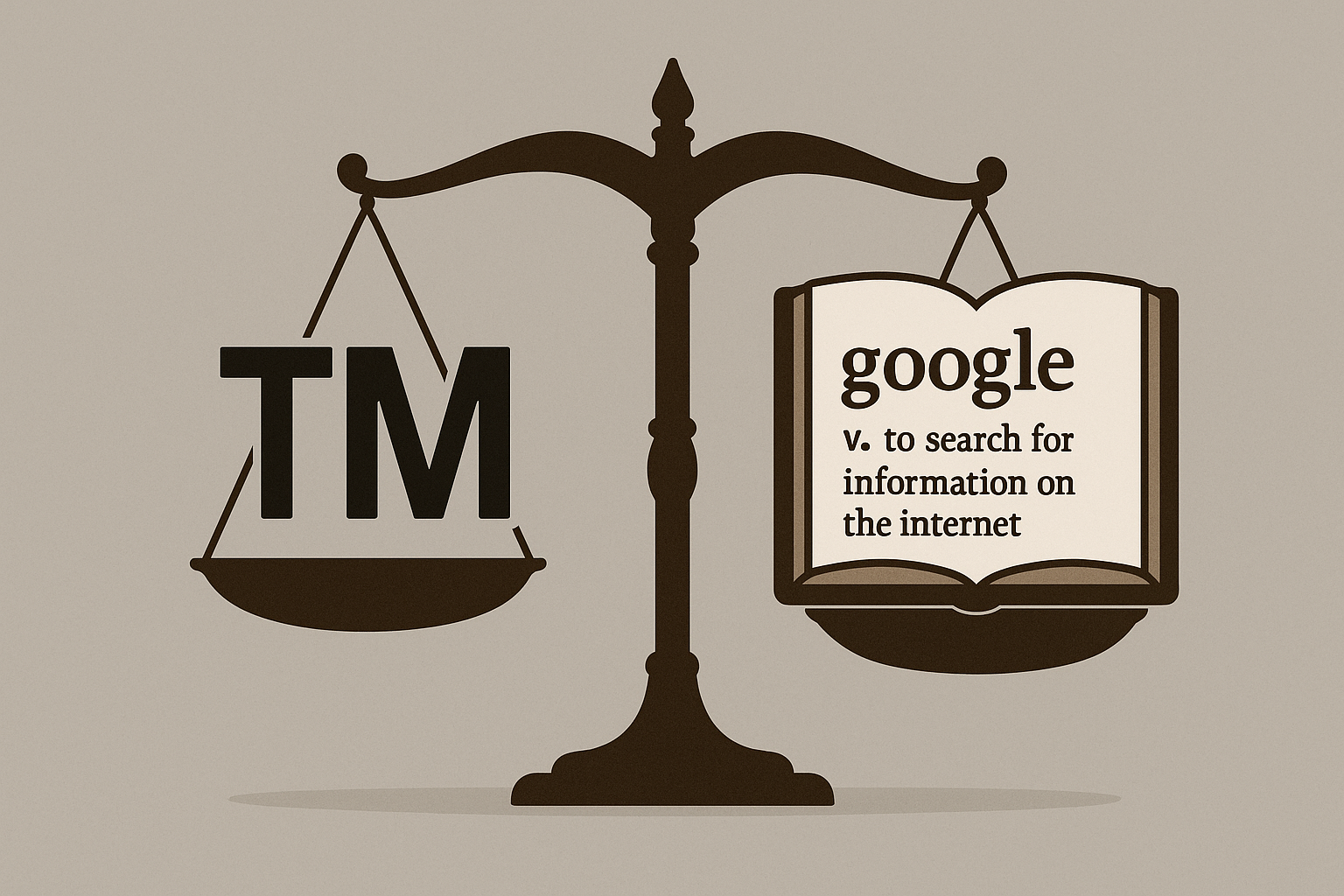

The solution didn’t come from a consensus, but from a debate that had been simmering for centuries: the Questione della Lingua, or “The Language Question.”

The Roots of a Standard: Dante’s Lingering Shadow

To understand why one dialect was chosen over all others, we have to travel back to the 14th century. At that time, Latin was the language of scholarship, law, and the Church. Writing in the local vernacular was seen as common, even provincial. But three literary giants from Tuscany changed everything. They are known as the Tre Corone, or “Three Crowns”:

- Dante Alighieri, who wrote his epic poem, The Divine Comedy, in his native Florentine.

- Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch), whose poetry in the vernacular set the standard for European lyricism for centuries.

- Giovanni Boccaccio, whose masterpiece, The Decameron, demonstrated the narrative power of the Florentine tongue.

By choosing to write their masterworks in the language of Florence, they elevated it to a level of unparalleled cultural prestige. For the next 500 years, anyone in the Italian peninsula who wanted to be considered educated or well-read learned to write in the style of the Three Crowns. The Florentine dialect became the gold standard for literature, a linguistic beacon that all others looked to for guidance.

However, this created a strange disconnect. While educated Italians wrote in a language based on 14th-century Florentine, they spoke their own regional languages at home. The chosen language was a literary artifact, not a living, breathing tongue for the masses.

Making Italians: The Manzoni Solution

After unification in 1861, the new government knew it needed a standard language for schools and administration. But which one? The archaic, beautiful language of Dante? A newly created language blending the best of all dialects? Or something else entirely?

The answer came from the era’s most influential writer, Alessandro Manzoni. His novel, I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed), was a national sensation, considered the most important work of Italian fiction. Manzoni, originally from Milan, was keenly aware of the language problem. He believed the national language should be based on a living, spoken model that still carried the prestige of its literary past.

His solution was simple and elegant: the standard for Italian should be the contemporary spoken language of the educated classes of Florence.

Famously, Manzoni undertook a process he called “rinsing his clothes in the Arno” (risciacquare i panni in Arno), the river that flows through Florence. He painstakingly revised his entire novel, stripping it of its Lombard influences and rewriting it to conform to the modern Florentine vernacular. The revised 1840 edition of I Promessi Sposi became the definitive blueprint for modern standard Italian.

In 1868, a government commission led by Manzoni formally recommended his model. The Florentine dialect—modern, vibrant, yet rooted in the legacy of Dante—was officially chosen as the language of the new Italian nation. It was to be taught in every school, used in every courthouse, and printed in every official document.

From the Classroom to the Living Room: The Power of Media

For decades, the project had mixed results. While schools taught the standard, dialects remained the language of the heart and home for millions. True linguistic unification was slow, hampered by poverty and illiteracy. The real catalyst for change wouldn’t be a book or a decree, but an electronic box.

The post-World War II economic boom brought prosperity and, crucially, television into Italian homes. The state broadcaster, RAI (Radiotelevisione italiana), became the most effective language teacher in the nation’s history. RAI adopted the Manzonian standard—a clear, carefully pronounced Italian—for all its programming.

One program, in particular, had a monumental impact. From 1960 to 1968, a show called Non è mai troppo tardi (“It’s Never Too Late”) aired in the early evening. Hosted by the charismatic teacher Alberto Manzi, it was a televised literacy class for adults. Using a simple blackboard and charming illustrations, Manzi taught millions of Italians how to read, write, and speak the national language. Classrooms were set up in bars and community centers across the country so people could watch together. In less than a decade, the show dramatically reduced illiteracy and gave the entire population a shared linguistic reference point.

News broadcasts, game shows, and American films dubbed into perfect standard Italian completed the job. For the first time, a farmer in Puglia and a factory worker in Turin were hearing and absorbing the exact same language every single day. Television succeeded where policy had struggled, creating a truly national spoken language in just a few decades.

A Living Language, A Rich Heritage

Today, virtually all Italians speak the national standard, a direct descendant of the language chosen by Dante and refined by Manzoni. But the dialects have not disappeared. They remain a powerful symbol of regional identity, a private language used with family and friends, and a source of cultural richness.

The making of the Italian language is a powerful reminder that a nation’s voice is rarely a simple accident of history. It is often a deliberate construction—a blend of cultural gravity, political will, and the transformative power of communication. It is a legacy to be inherited and a project to be built, all at the same time.