Imagine your family. You and your siblings might share your mother’s eyes or your father’s sense of humour. These are inherited traits, passed down through a shared lineage. Most of the world’s languages work the same way; French, Spanish, and Italian share features because they all descend from Latin. But what if you started to look and sound just like your next-door neighbour, despite having no shared ancestry? What if you started finishing their sentences, not just because you know them well, but because your very way of structuring thoughts had begun to merge?

Welcome to the Balkans, a region not just of complex history and stunning landscapes, but also of a profound linguistic mystery: the Balkan Sprachbund.

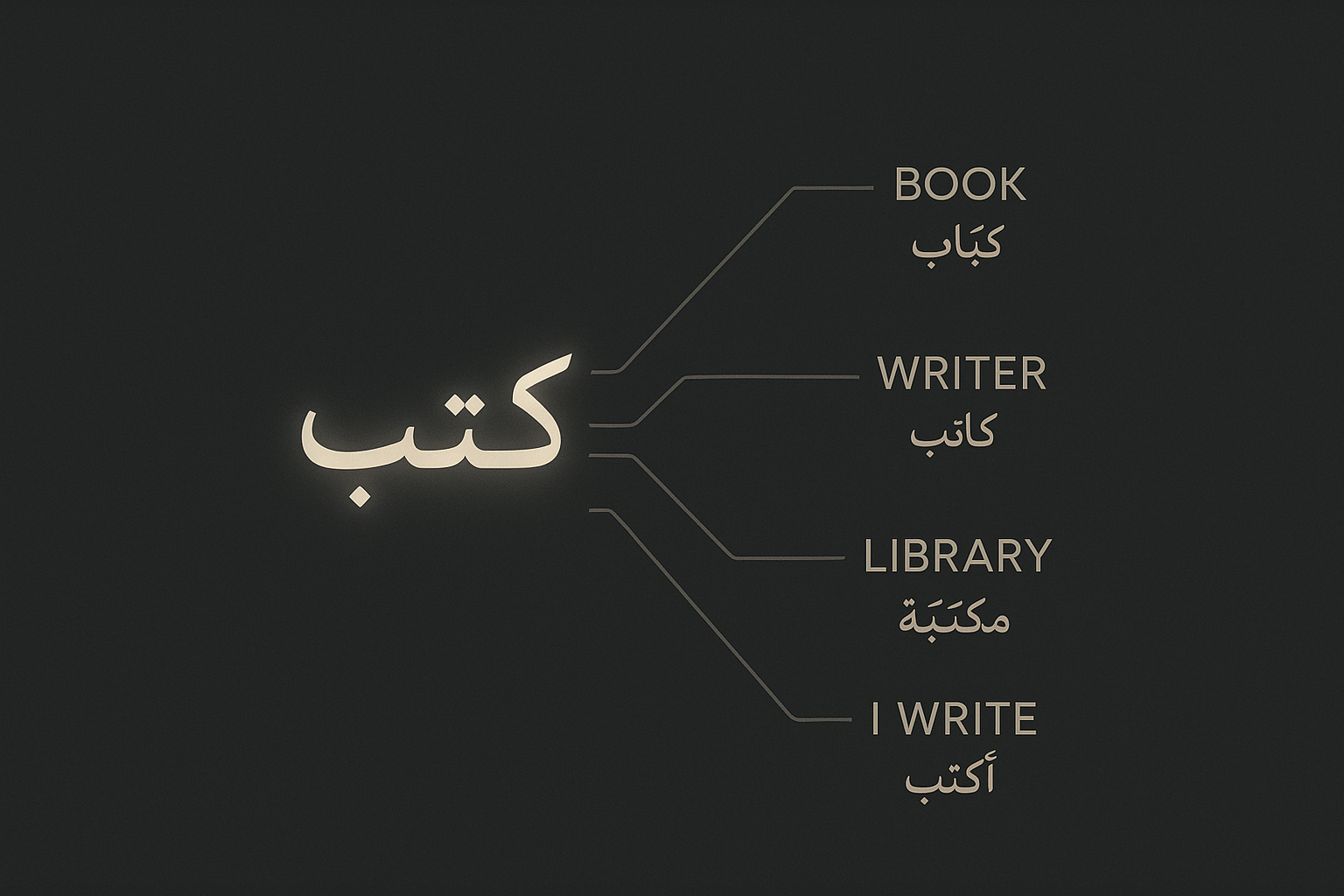

What is a “Sprachbund,” Anyway?

Before we journey into the heart of the Balkans, let’s unpack that rather German-sounding term. A Sprachbund (pronounced SHPRAHK-boont), which translates to “language league” or “linguistic area,” is a group of languages that have become structurally similar to one another through geographic proximity and prolonged contact.

This is the crucial difference from a language family. Members of a language family are genetically related; they share a common ancestor. Members of a Sprachbund are more like grammatical co-conspirators. They might come from entirely different families, but after centuries of their speakers living together, trading, fighting, and intermarrying, the languages themselves have rubbed off on each other, borrowing not just words, but the very scaffolding of grammar.

Meet the Members of the Balkan Club

The Balkan Sprachbund is a textbook example of this phenomenon, a linguistic melting pot simmering for over a millennium. The cast of characters is incredibly diverse, hailing from different branches of the Indo-European tree:

- Albanian: A language isolate, forming its own independent branch of the Indo-European family.

- Romanian: A Romance language, descended from the Latin spoken by Roman colonists.

- Bulgarian and Macedonian: South Slavic languages, closely related to each other but distinct from other Slavic tongues like Russian or Polish.

- Greek: The sole member of the Hellenic branch, with an ancient and storied history of its own.

- Serbo-Croatian (specifically its southern and eastern dialects): Another South Slavic language that shares many, though not all, of the core features.

- Romani (Balkan dialects): An Indo-Aryan language, with roots tracing all the way back to India.

These languages are not “cousins” by birth. They are neighbours who became so intertwined that they created a web of shared linguistic DNA. So, what are these strange similarities that tie them together?

The Telltale Signs: Shared Grammar Across Borders

The similarities in the Balkan Sprachbund go far beyond a few borrowed words for food or tools. They cut to the very core of how sentences are built. Here are some of the most famous “Balkanisms.”

1. The Case of the Missing Infinitive

In most European languages, the infinitive—the basic “to do” form of a verb—is essential. We say “I want to see” or “I need to write.” But in the heart of the Balkans, this structure has largely vanished. Instead, they use what’s called a subjunctive clause, which sounds a bit like “I want that I see.”

Let’s look at the phrase “I want to go”:

- Romanian: Vreau să merg. (Literally: “I want that I go.”)

- Bulgarian: Искам да отида (Iskam da otida). (Literally: “I want that I go.”)

- Albanian: Dua të shkoj. (Literally: “I want that I go.”)

- Greek: Θέλω να πάω (Thélo na páo). (Literally: “I want that I go.”)

For Romanian, a Romance language, this is bizarre. Its cousins like Italian (Voglio andare) or French (Je veux aller) all use a standard infinitive. The same goes for the Slavic members; Polish would say Chcę iść. This shared grammatical workaround is a hallmark of the Sprachbund.

2. The Article That Comes Last

In English, we place the definite article “the” before a noun: the house, the dog. The same is true for most European languages (la casa, le chien). The Balkan languages decided to do things differently. Several of them attach the article to the end of the noun, a feature known as a “postposed definite article.”

Consider the word for “man” and “the man”:

- Romanian: om → omul

- Albanian: burrë → burri

- Macedonian: маж (maž) → мажот (mažot)

- Bulgarian: мъж (măzh) → мъжът (măzhăt)

This is a particularly striking feature. It’s not something languages tend to borrow lightly. Interestingly, Greek is the notable exception here; it keeps its article out front (o ánthropos), reminding us that not every member adopts every single feature.

3. Future Tense with “To Want”

How do you talk about the future? Many Balkan languages form their future tense using an auxiliary verb that originally meant “to want.” Over time, this word bleached of its original meaning and became a simple grammatical marker for the future.

- In Romanian, the formal future uses a form of a vrea (“to want”): Voi citi (“I will read”).

- In Greek, the future particle tha (θα) is a shortened form of thélo na (“I want that…”): Tha gráfo (“I will write”).

- The same pattern appears in Serbian/Croatian, Bulgarian, and Albanian.

This is the linguistic equivalent of deciding to use a spoon not for soup, but as a standard tool for hammering nails, and all your neighbours agreeing it’s a great idea.

How Did This Happen? A History of Contact

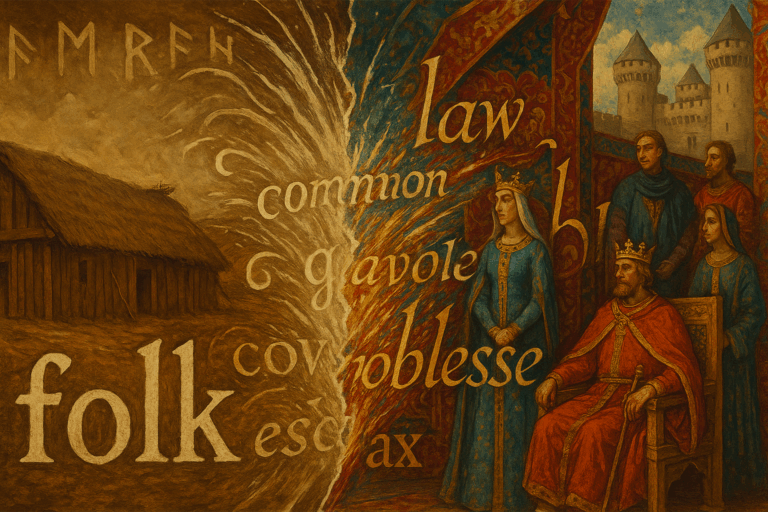

A linguistic anomaly this profound doesn’t happen in a vacuum. The Balkan Sprachbund is the direct result of centuries of intense, sustained human interaction under the umbrellas of vast, multicultural empires.

The migrations of Slavic peoples, the pastoral Vlach (ancestors of modern Romanians) shepherds moving their flocks across mountains and borders, and the persistent cultural gravity of the Byzantine (Greek-speaking) and later the Ottoman (Turkish-speaking) Empires created a perfect storm. For hundreds of years, communities speaking Albanian, Greek, Slavic, and Romance dialects lived side-by-side. Widespread bilingualism was not a choice; it was a necessity for trade, administration, and daily life.

In this environment, it wasn’t enough to just learn vocabulary. To truly communicate effectively, speakers began to subconsciously adopt the sentence structures and grammatical patterns of their neighbours. It was a slow, organic process of convergence, a grassroots standardization that happened in marketplaces and mountain pastures, not in academic halls.

A Testament to Connection

The Balkan Sprachbund is more than a linguistic curiosity. It’s a living monument to human history and the deep, transformative power of cultural contact. It shows us that language is not a static, walled-off system, but a fluid, dynamic entity that reflects the lives of its speakers.

The languages of the Balkans, despite their separate origins, have become grammatical brethren. They are a powerful reminder that even without a shared past, centuries of a shared present can forge a common future, weaving a linguistic tapestry as rich and complex as the region itself.